Pandemic Leaves Firms Scrambling for Cybersecurity Specialists

Two years after the start of the coronavirus pandemic, companies are finding cybersecurity workers increasingly difficult to find, harder to retain, and more demanding of concessions, according to a report published this week by the IT industry association ISACA.

The report, based on a survey of more than 2,000 cybersecurity professionals, finds that 60% of companies had problems retaining cybersecurity specialists in 2021, up from 53% of companies at the start of the pandemic in 2020. Businesses continue to have to adapt to the expectations of workers, including allowing more remote work and the time for continuing education, or else lose workers to other companies because of poor financial incentives, limited promotion opportunities, and high stress, according to ISACA’s State of Cybersecurity 2022 report.

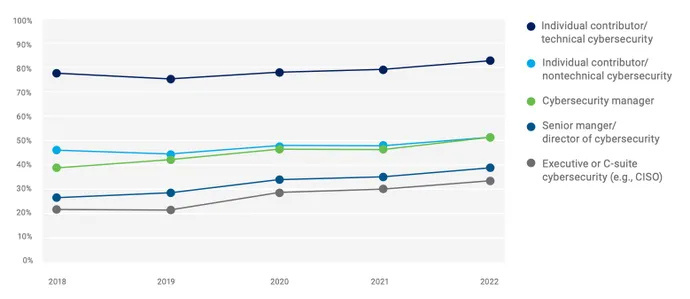

Overall, demand has increased for every level of cybersecurity worker, but especially for technical practitioners, says Jonathan Brandt, director of professional practices and innovation at ISACA.

“The individual technical practitioners will always be in demand, and that will be the toughest piece for us to solve,” he says. “Right now, it is a never-ending shell game of finding the right sets of skills, which lends itself to pipeline challenges, because the traditional ways of developing talent takes too long compared to how quickly the landscape changes.”

The survey underscores that pandemic-related issues are likely exacerbating the talent gap. Most companies appear to have understaffed cybersecurity groups, with 62% of professionals considering their group somewhat or significantly understaffed, according to the report, despite a previous study that found nearly 700,000 cybersecurity specialists were added to the global workforce over the past year.

Nearly 60% of cybersecurity professionals see other companies poaching employees as a big reason for the current lack of knowledgeable workers, but a host of other factors indicate that working conditions have convinced many to swap jobs. Nearly half believe current jobs have poor financial incentives (48%) or limited opportunities for promotions (47%), while 45% point to high stress levels. Many workers want employers to offer more remote-work opportunities and flexible work policies, according to the survey.

“Flexible work expectations increased due to the pandemic and have become weighty considerations when employees evaluate potential career moves,” ISACA states in the report. “In 2021, employees pushed back against mandates to return to a physical office space, resulting in many enterprises revising or curtailing plans to return to in-office work. This issue and high-wage expectations have led to an intense battle for talent.”

Part of the problem is that few companies have training programs to turn IT workers into cybersecurity professionals. Most companies hope to hire technical experts who are ready to work, with little regard to the fact every company and every industry has different technologies, risks, and threat landscapes, says ISACA’s Brandt.

“It is highly unreasonable for companies to expect turn-key hires,” he says. “There is no one-size-fits-all.”

If anything, security technology is quickly returning to what it was in the early 2000s, when pretty much everything was vendor-driven and security professionals had to learn to operate specific vendors’ product lines, he says.

“I can use open source software to teach the concepts and help you connect the dots, but if every company out there has its own vendors’ products, there is the expectation that the cybersecurity workers will be made to go through that vendor pipeline as well.”

Pipeline Problem

The study shows the lack of an effective pipeline to turn out young cybersecurity professionals: Nearly two-third of cybersecurity experts are between the ages of 35 and 54, with only about 11% of workers under 35. Cybersecurity workers coming out of college programs are relatively uncommon; many more are coming from non-technical programs or finding ways to train themselves in cybersecurity later in life.

The results show that cybersecurity professionals do not necessarily need a technical background, Brandt says.

“If you look at a security engineer or a security architect, they need the IT background,” he says. “But if you are talking about analysts, there is a reason why we hear stories of people coming from liberal arts background and doing really well on an investigative side.”

Companies are also getting in their own way, with human resources not effectively working with security groups to fill their vacancies. Currently, companies take three to six months to fill a cybersecurity position with a qualified candidate, according to the ISACA report. The most important attributes of a good candidate are prior hands-on experience, credentials, and hands-on training, with good communication and leadership important in all candidates and cloud-security skills the most in-demand technical skill.

Overall, the HR department only “occasionally” understands the cybersecurity requirements to properly screen candidates, the survey found.

Those issues, paired with bootcamps and alternative programs that are not teaching job-ready skills, means that there is a mismatch between many candidates and what companies think they want, Brandy says.

“I think the money is there, even if the budgets continue to flat line … but on the resource side of things, the people, the human capital, we have so much more work to do,” he says. “We have a lot of folks that spend a lot of hard-earned money and dollars who go through pipeline programs who spend a lot of money and work gaining skills, and then can’t get a job, and we should be ashamed of that.”

Read More HERE