Nearly All Modern CPUs Leak Data To New Collide+Power Side Channel Attack

A new side-channel attack method that can lead to data leakage works against nearly any modern CPU, but we’re unlikely to see it being used in the wild any time soon.

The research was conducted by a group of eight researchers representing the Graz University of Technology in Austria and the CISPA Helmholtz Center for Information Security in Germany. Some of the experts involved in the research discovered the notorious Spectre and Meltdown vulnerabilities, as well as several other side-channel attack methods.

The new attack, dubbed Collide+Power, has been compared to Meltdown and a type of vulnerability named Microarchitectural Data Sampling (MDS).

Collide+Power is a generic software-based attack that works against devices powered by Intel, AMD or Arm processors and it’s applicable to any application and any type of data. The chipmakers are publishing their own advisories for the attack and the CVE-2023-20583 has been assigned.

However, the researchers pointed out that Collide+Power is not an actual processor vulnerability — it abuses the fact that some CPU components are designed to share data from different security domains.

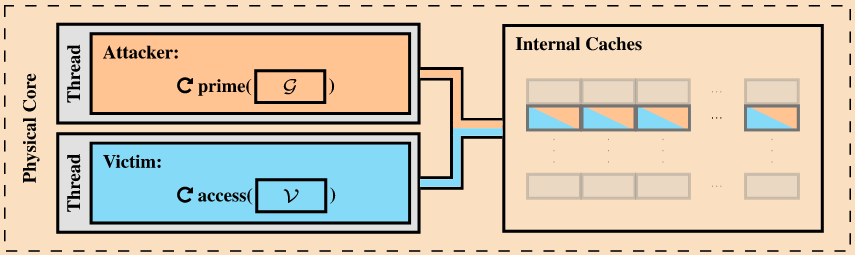

An attacker can leverage such shared CPU components to combine their own data with data from user applications. The attacker measures CPU power consumption over thousands of iterations while changing the data they control, which enables them to determine the data associated with the user applications.

An unprivileged attacker — for instance, by using malware planted on the targeted device — can leverage the Collide+Power attack to obtain valuable data such as passwords or encryption keys.

The researchers noted that the Collide+Power attack enhances other power side-channel signals, such as the ones used in the PLATYPUS and Hertzbleed attacks.

“Previous software-based power side-channels attacks like PLATYPUS and Hertzbleed target cryptographic algorithms and needed precise knowledge of the algorithm or victim program executed on the target machine. In contrast, Collide+Power targets the CPU memory subsystem, which abstracts the precise implementation away as all programs require the memory subsystem in some way. Furthermore, any signal reflecting the power consumption can be used due to the fundamental physical power leakage exploited by Collide+Power,” they explained.

The researchers have published a paper detailing their work, as well as a dedicated Collide+Power website that summarizes the findings.

They describe two variants of the Collide+Power attack. In the first variant, which requires hyperthreading to be enabled, the attack targets data associated with an application that constantly accesses secret data, such as an encryption key.

“The victim constantly reloads the secret into the targeted and shared CPU component during this process. An attacker running on a thread on the same physical core can now use Collide+Power to force collisions between the secret and attacker-controlled data,” the researchers explained.

The second variant of the attack does not require hyperthreading and it does not require the target to constantly access secret data.

“Here an attacker exploits a so-called prefetch-gadget within the operating system. This prefetch gadget can be used to bring arbitrary data into the shared CPU component and again force data collisions and recover the data,” the experts said.

While in theory the attack method could have significant implications, in practice the data leakage rates are relatively low and the method is unlikely to be exploited in the wild against end users any time soon.

The researchers have managed to achieve a data leakage rate of 4.82 bits per hour in a scenario where the targeted application constantly accesses secret information and the attacker can directly read the power consumption of the CPU via the Running Average Power Limit (RAPL) interface, which directly reports a CPU’s power consumption. At this rate, it would take the attacker several hours to obtain a password and several days to obtain an encryption key.

In special circumstances, the researchers found that an attacker could achieve much higher data leakage rates, up to 188 bits/h.

“An attacker could achieve the 188 bits/h leakage rate depending on the targeted application and the secret representation in memory. For example, if the key or password is in a cache line multiple times,” Andreas Kogler, one of the TU Graz researchers involved in the project, told SecurityWeek.

On the other hand, in real-world attack simulations, the researchers encountered practical limitations that significantly lowered leakage rates — more than one year per bit with throttling.

Despite the relatively small risk that the attack poses today, the Collide+Power research highlights potential issues and paves the way for future research.

As for mitigations, preventing such data collisions at the hardware level is not an easy task and would require the redesign of general-purpose CPUs. On the other hand, attacks can be prevented by ensuring attackers cannot observe power-related signals — this type of mitigation applies to all power side-channel attacks.

Related: AMD CPU Vulnerability ‘Zenbleed’ Can Expose Sensitive Information

Related: Chipmaker Patch Tuesday: Intel, AMD Address Over 100 Vulnerabilities

READ MORE HERE