Security Review: A Counterfeit, $100 iPhone X

“I found an iPhone X for $100,” Motherboard reporter Sarah Emerson messaged me while she was on a reporting trip in Shenzhen, China earlier this year. “You want one?”

The answer, obviously, was yes. A few months earlier, I had traveled to Australia with iFixit to watch as it became one of the first teams to tear down the $999 iPhone X. I’ve written extensively about independent repair professionals who source their iPhone repair parts from third-party Chinese factories. I needed to know what a $100 iPhone would be like. I eagerly checked my mailbox every day for a week until a white iPhone box arrived. It looked like a real iPhone box with images and text that was a little blurry. I opened it.

In the back of my mind, I thought that maybe we’d just somehow gotten an insane deal on a real iPhone X. What was in the box was far more interesting.

Inside was a working smartphone capable of performing most of the functions that smartphones do. In that sense it is not a “fake” phone, but after using it, giving it to an independent cybersecurity company to probe, and disassembling it, it became clear that it wasn’t, as the box says, “Designed by Apple in California.”

The Phone

Image: Jason Koebler

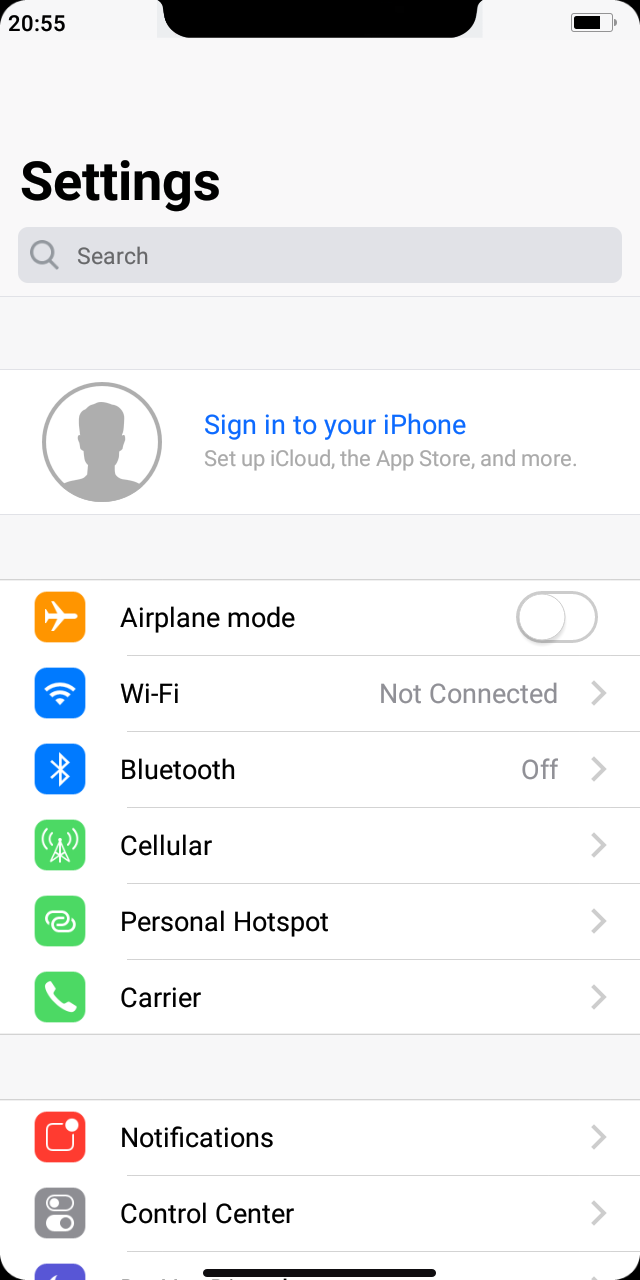

The phone looks like an iPhone X. It has the same form factor, most of the same detailing, no home button, the same volume rockers and side buttons, a working Lightning port, and the same speaker holes on the bottom of the phone. It also has pentalobe screws on the bottom of the device, just like an iPhone. It even comes with an instruction manual telling you how to set up Face ID. I looked up the IMEI number—essentially a serial number given to every smartphone—listed on the back of the box, and it corresponds to an iPhone X, though I have no way of telling whose.

When turning the phone on, the Apple logo shows up, and it boots to something that looks very much like iOS. It has the same default lock screen that the iPhone launches with, and you can launch the camera or flashlight from it. It uses the same logos, appears to have the same default apps, and generally seems as though you are using an iPhone.

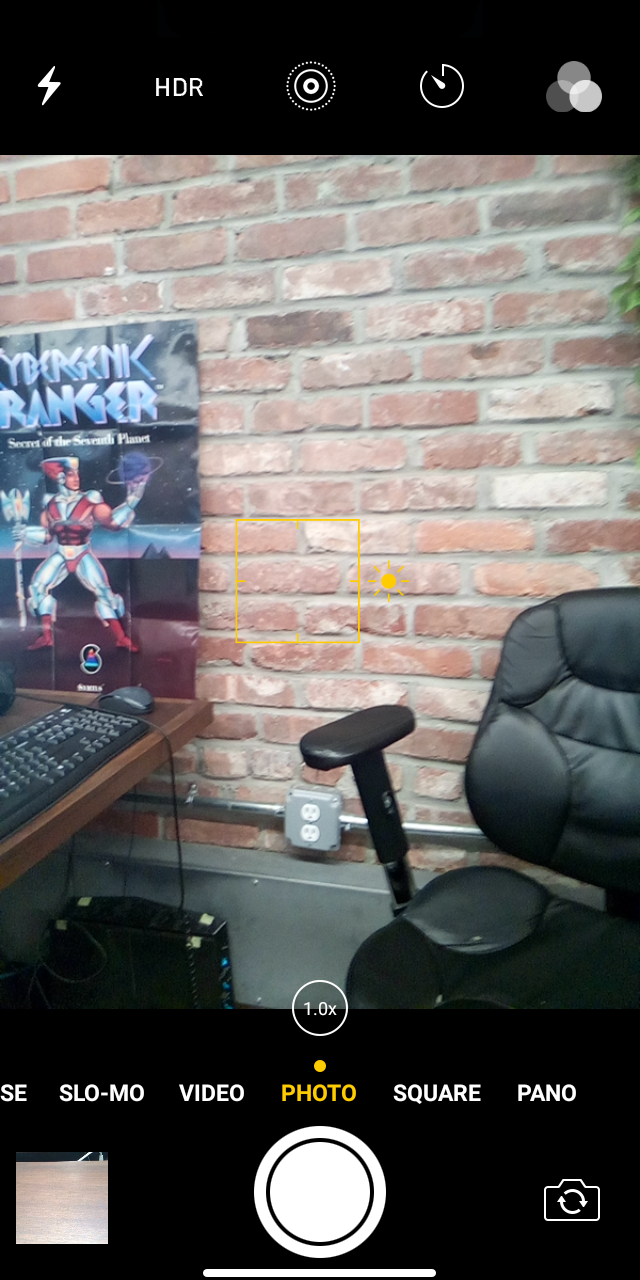

It quickly became clear this isn’t iOS, though. For one, the sensor bar at the top that creates the dreaded “notch” doesn’t exist on this phone. Instead, the notch has been lovingly recreated in software. The device feels sluggish and underpowered while switching apps. The camera is clearly kinda blurry.

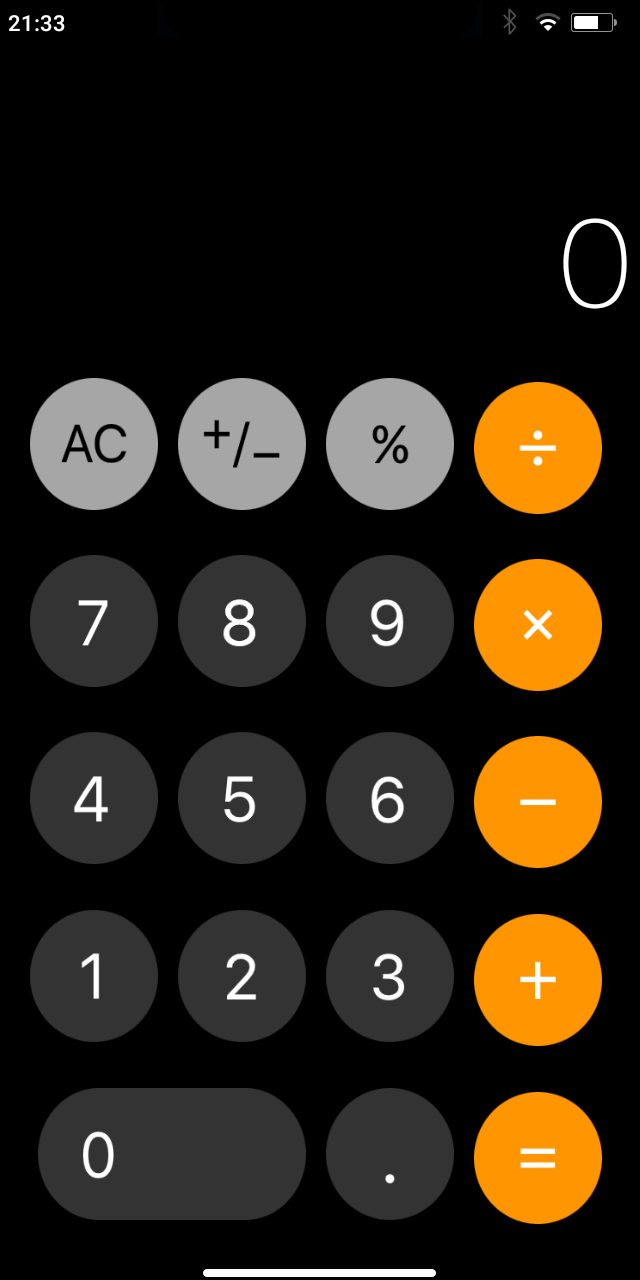

But still, if the phone isn’t an iPhone, it isn’t obvious what it actually is. Many of the apps look identical to their iOS versions. The calculator and stocks apps are seemingly identical to those in iOS. The camera menus and interface look the exact same as the one in iOS. The settings menu looks close-to-identical and has many of the same settings you’d find on an iPhone. The Mail app is the best approximation; I don’t use the default Mail app on my own iPhone, but the setup process and functionality seem from an end-user point-of-view as basically the same as the real thing.

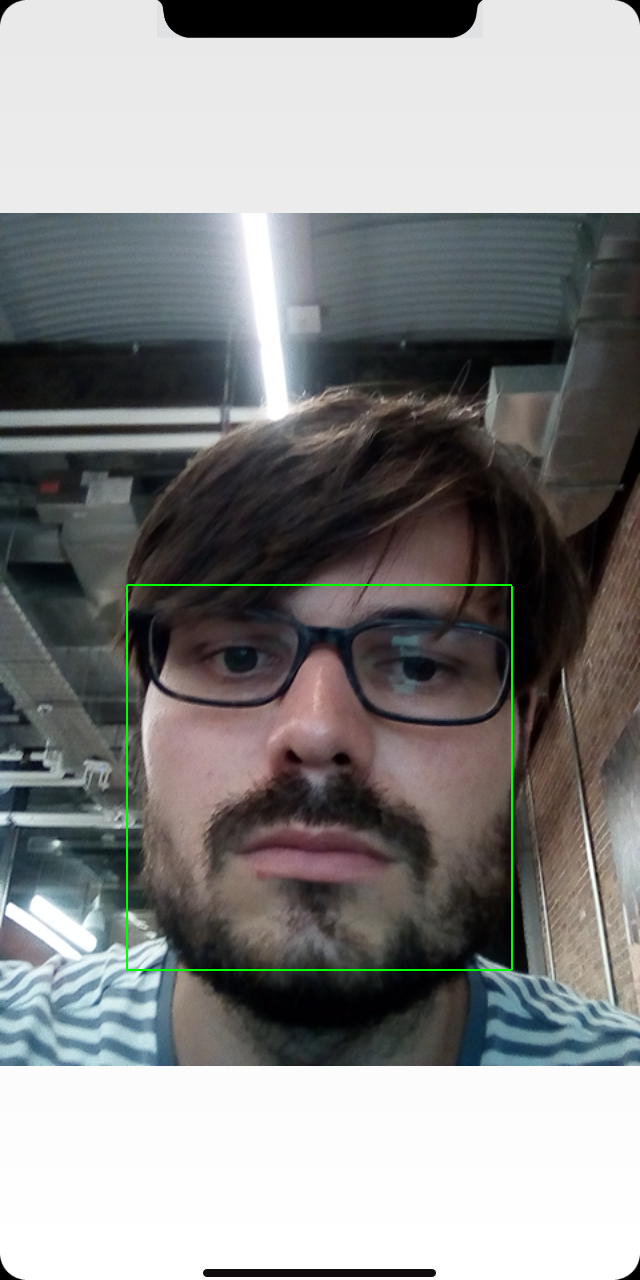

Image: Jason Koebler

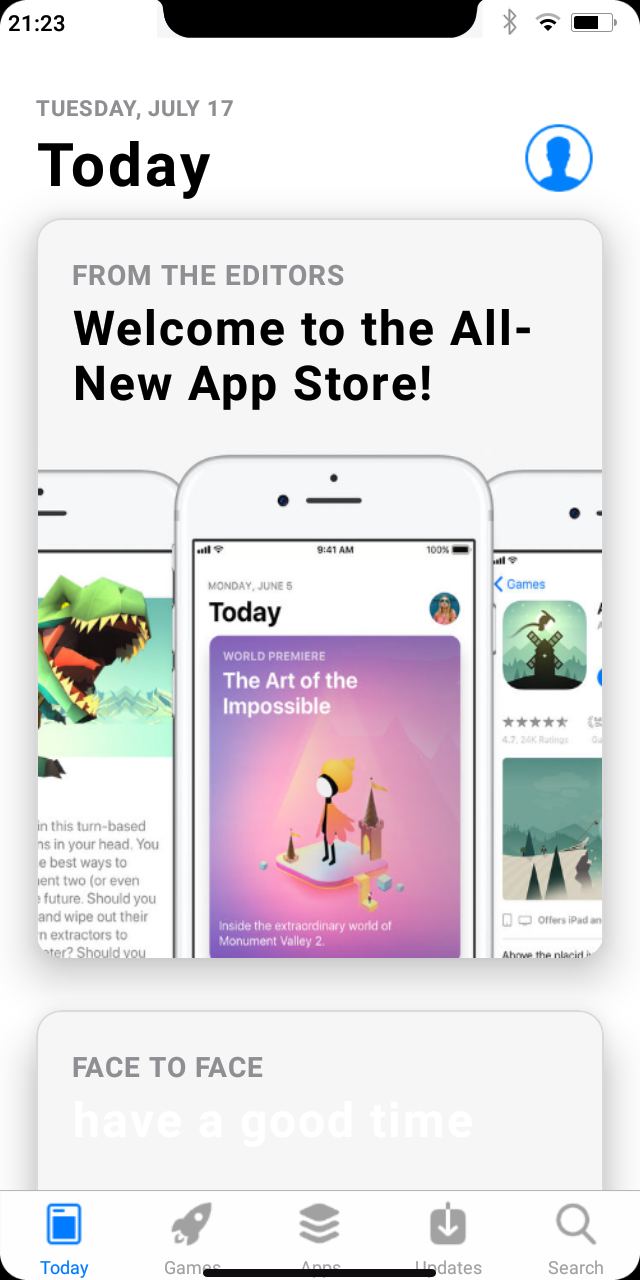

Once I started trying some of Apple’s more recent and advanced features, though, things started going off the rails. Siri’s graphical interface has been recreated, but it doesn’t really work. My favorite thing about the phone is its “Face ID” system. I clicked over to Face ID in the settings menu, clicked “Add a Face ID,” and was hilariously bounced over to the camera, which did manage to draw a green box around my face. It said “Face Added,” and closed. I was then able to unlock the phone with my face. So was literally anyone else who put their face in front of the phone.

Clicking around further betrayed the phone’s actual software: the keyboard is clearly an Android keyboard; when the reskinned App Store crashed, I got a popup notifying me that the “Google Play Store” had malfunctioned. The “Weather” app is just Yahoo! Weather. The Health App is a third party thing that asked me to click cartoon avatars selecting whether I was a “boy or girl.” The “Podcasts” app just opens YouTube. Apple Maps opens Google Maps.

The phone, then, is a device that looks just like an iPhone but is actually an Android that has been reskinned from top-to-bottom to seem as close to an iPhone as is possible.

I was unfortunately unable to get the phone to connect to an American cellular network on a throwaway SIM card, but I did connect the phone to a few public Wi-Fi networks to approximate daily use (I also didn’t login to any of my own accounts, and didn’t connect it to any of the normal Wi-Fi networks for reasons that’ll become clear in a moment.) It felt largely like using a phone that was maybe a few years old, with buggy software that nonetheless mostly worked. I was able to send emails from throwaway accounts, browse the internet, take photos and screenshots, and generally complete tasks with the phone.

Probing the phone

One day after work, Motherboard security reporter Lorenzo Franceschi-Bicchierai and I took the phone to Trail of Bits, a security research and consulting firm in New York City, to try to figure out exactly what was running under the hood of what—at first glance—looks like a real iPhone running real iOS.

The researchers were initially wowed with the device, and were surprised that it used a Lightning port and a software notch. They assumed that the device was likely insecure, and kept it in a faraday bag, which blocks all incoming and outgoing wireless signals, to keep it from potentially causing any trouble at their office. A few weeks later, Trail of Bits researcher Chris Evans wrote up an initial security report for us.

According to Evans, the phone runs a version of Android with a patchwork of code taken from several different sources. The phone is also loaded with backdoors and malicious apps.

“If it isn’t outright malicious its overall security is pretty much non-existent,” Evans told us.

The apps, which appear to come from several different online sources, is where it “gets really bad,” as Evans put it in the report shared with Motherboard. Security features such as permissions, regulation, or sandboxing (which keep a vulnerability in one app from affecting other parts of the phone) are “almost non-existent.”

Several of the stock fake Apple apps such as Compass, Stocks, Clock ask for “invasive permissions,” such as reading text messages. It’s unclear if this is a sign that the developers were mediocre or malicious, Evans wrote.

“The mismash of default apps preinstalled on the phone I was given are horribly insecure (if not outright malware),” Evans said.

Evans also found “plenty of evidence” of a “wide range of backdoors,” perhaps written by several developers. The fake Safari app uses custom libraries that open a backdoor and allow hackers to run code on the phone remotely. Last year, Google removed 500 apps that had more than 100 million downloads combined from the Play Store because they included one of those libraries.

The fake iPhone also includes two more potential backdoors. One is the notorious ADUPS, a service made by a Chinese company that provides over-the-air firmware updates that is widely considered to be a backdoor. The other is an app called LovelyFont that looks like an “invasive backdoor” that has almost all permissions and potentially leaks data, such as the phone’s IMEI, MAC, and serial number, to a remote server, according to Evans.

Training “Face ID”

To make matters worse, the phone logs the iCloud username and password in a database that’s broadcast to the whole system and can be read by any service and application, according to Evans (this means that if you happen to find yourself in possession of one of these, you should definitely not login to iCloud on it.)

Interestingly, there was an attempt to make “Siri” work properly: It “seems to be a legitimate, albeit poor attempt at integrating a voice application launcher,” Evans wrote; all queries sent through “Siri” are routed through a Chinese voice command library called iFlyTek, and weather checking and translation are sent to a Baidu server.

The phone’s hardware specs are less scary, but still somewhat shady. The phone’s system-on-chip is the MT6580, “one of many in a line of incredibly cheap boards that are a mainstay in Chinese Android phones,” made by Taiwanese firm Mediatek, he wrote. Its operating system is based on Android 6 Marshmallow, which was originally released in 2015, with a modified kernel source, according to Evans’s report. The phone’s firmware was created using a software platform called “Chinese Miracle 2” that is widely available.

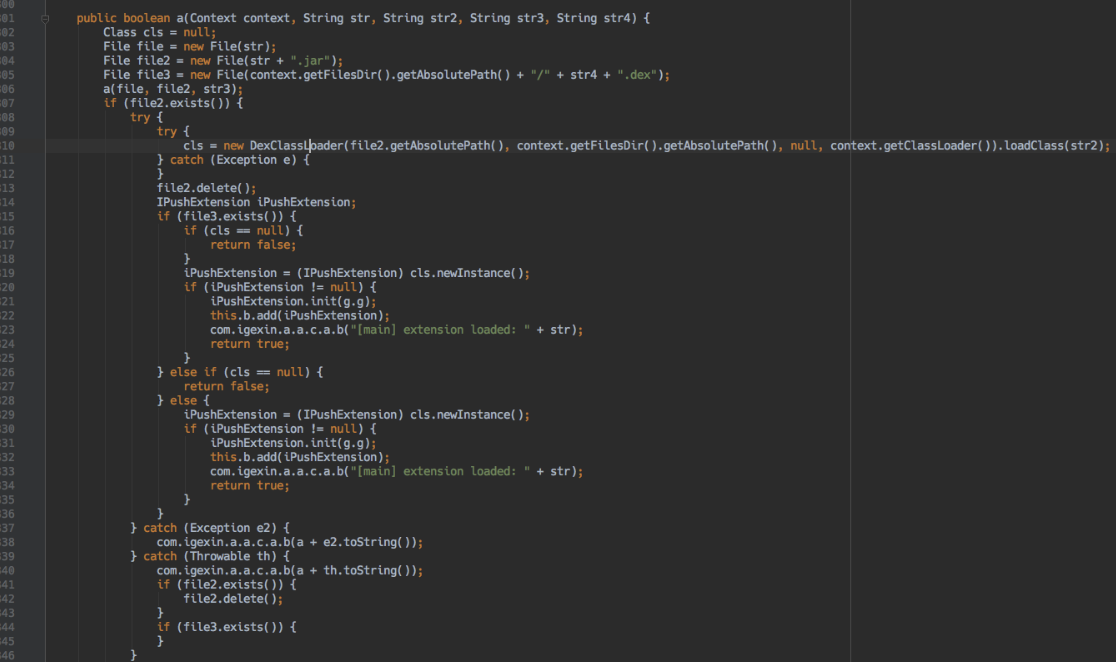

Examples of code loading remote extensions and managing downloads.

Evans was also able to explain why the phone’s software looks so much like iOS. When the phone boots for the first time, a custom app mimics iOS onboarding, adapting it to Android’s settings. The Settings app looks like an iPhone Settings app but it’s also written to apply to Android system options, and when there’s no equivalent, it just does nothing. To complete the faux iOS look, the phone uses a custom launcher that mimics iOS instead of the stock Android launcher.

It was hard for Evans to figure out exactly who actually developed the phone, and he warned us that the evidence he found is inconclusive. The developer is almost definitely Chinese, according to Evans. But where they got the code is less clear. Evans found that the firmware appears to have been downloaded from forums where where members share ROM clones and tools.

In any case, while the phone is undoubtedly quite cool, Evans came to the conclusion: “I wouldn’t use this phone if I valued my privacy/passwords/information, etc.”

What’s Inside

When the iPhone X launched, I was with iFixit to look at what was inside it. So naturally I had to open this thing up, knowing that I’d probably break it in the process because I didn’t have any sense of how it was put together in the first place.

Like any other iPhone, the device has two pentalobe screws next to the Lightning port. I grabbed my screwdriver and started unscrewing them. And they didn’t go anywhere, or come loose. I shoved some tweezers in there and pried them out. It turns out they weren’t screws at all. Instead, they were little bolts (no threads) that didn’t actually do anything and were just for show.

I attached a suction cup to the screen and started pulling, and began unclipping the plastic clips that held the screen on. The device opened horizontally rather than vertically, just like recent iPhone models (and unlike, say, the iPhone 5S, which opens from the bottom.)

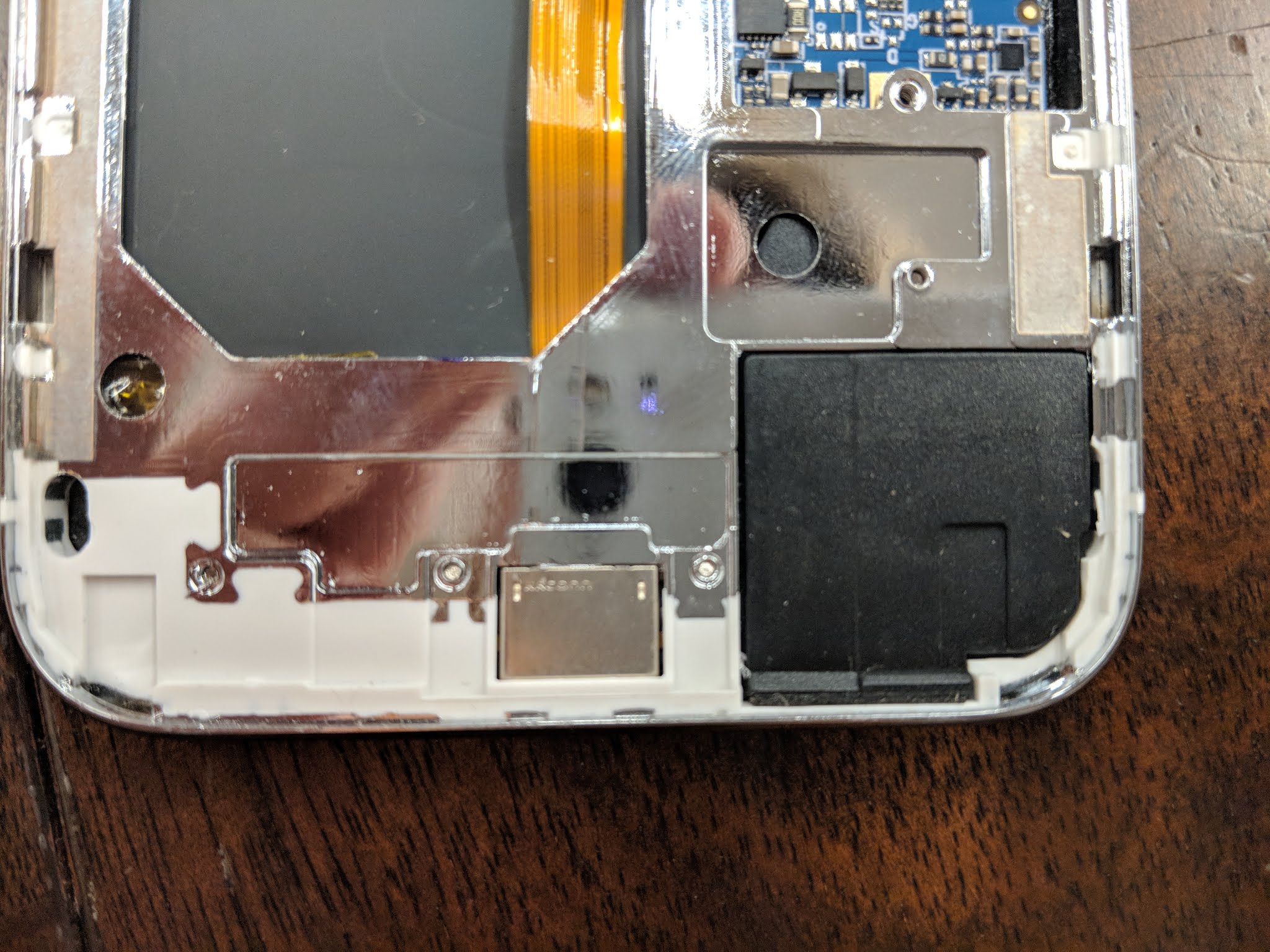

The interior layout is similar to the iPhone X, in that the battery takes up the bulk of the left side of the device, the charging port is at the bottom, and the “logic board,” or whatever you’d like to call it in this case, is on the right side of the device. The similarities pretty much end there.

The last few moments of this phone’s life.

When we tore down the iPhone X, iFixit CEO Kyle Wiens called it “the pinnacle of electronic engineering.”

“It’s the most thought out, carefully designed product in the history of the world,” he said, referring to the hundreds of thousands (if not millions) of work hours and millimeter-precise design choices made by Apple that went into the device.

This is the inside of a real iPhone X. Image: iFixit

This phone is clearly not that.

“There’s a lot more space in the layout,” iFixit’s Adam O’Camb told me. “On the iPhone X, everything is very packed together. On this, space is used superficially on the board.”

This is the inside of the phone we bought.

There’s lots of plastic that seems to be included to take up space so that the interior components won’t shift; there’s clearly no Haptic Engine or Face ID sensor bar (though there are, of course, cameras.) The battery looks like a standard smartphone battery rather than the dual cell battery that’s in the iPhone X, and the logic board looks like a plug-and-play from something else. Even to my relatively untrained eyes, the chips on it are much larger, indicating that they’re older and probably much less expensive than what’s used in the iPhone X (considering that we could have bought 10 of these for the price of one iPhone X, that makes sense.)

“It’s clearly a couple generations behind, as well as having a little bit of a dumbed-down front sensor and obviously not the same face-recognition software,” O’Camb said. It also doesn’t have an OLED display.

Rivets, everywhere!

Most interesting, though, is how the phone appears to be assembled. It’s filled with metal brackets, as well as a shield that holds the battery in. Apple gets a lot of shit for gluing down its battery (making it difficult to replace), but this metal shield is definitely worse. That’s because I only found one single screw in the entire phone. The rest of the phone’s components are secured with metal rivets that are punched together, which effectively make the phone disposable. Replacing the battery would mean destroying the phone entirely, and disassembling this thing would basically require me to cut through metal or crack it in half.

“Rivets are bad for repair because they make it more difficult to take apart and then you can’t really replace them,” O’Camb said. “The reasoning behind their use is because it’s just cheaper. Using a rivet gun is cheaper and faster than screwing everything together.” O’Camb added that rivets have a bit more margin for error than screws—if a screw is misplaced on an iPhone, it could destroy the phone (this is often called “long screw damage” when a user botches a repair and tries to screw the wrong screw into a hole.) If a rivet is off by a few millimeters, it’ll still hold tight.

Internally, then, the device seems to contain a handful of old smartphone components that are assembled in a layout somewhat similar to that of the iPhone and fastened together as cheaply and quickly as possible. While I did break the phone while I was disassembling it (the screen was also riveted on in a few spots), I was unwilling to cut through the metal to see underneath the shield, primarily because I didn’t want to start a fire in the VICE office by puncturing the battery.

Should you buy it?

I would not necessarily recommend using this phone as your daily driver. But it is by far the most interesting piece of technology I’ve come across this year.

As Sarah Emerson reported earlier this year, the line between counterfeit and authentic is often muddled; Shanzhai electronics once referred exclusively to the counterfeit market, it now refers to original inventions, cloned electronics, hybrid devices, and so-on. Sarah said that she didn’t see many of these devices for sale in the electronics markets she went to: “Mostly, people were selling not-obviously-fake ones for roughly the same price as market value,” she told me. “It’s possible those versions were also reassembled, or swiped from delivery trucks in places like Hong Kong before making it to Shenzhen.”

Apple would certainly call this phone “counterfeit,” and it quite egregiously uses lots of Apple’s trademarks and copyrights. But that doesn’t mean it’s worthless or not an interesting engineering or manufacturing feat. It’s a functioning smartphone and would certainly fool a bystander if you happened to be using it that costs 10 times less than the original; it’s also the only Android phone I’ve ever seen that charges and connects to computers using Apple’s Lightning port. In that sense, it actually is a hybrid between an iPhone and an Android.

It’s hard to say where this device fits in in Apple’s aggressive war on independent repair and third party replacement parts. It’s clear that factories in China besides Foxconn can make high quality electronics, and many of them can and do make parts that are compatible with and sometimes interchangeable with the iPhones that Apple sells. Aside from the Lightning port, this phone doesn’t use any parts that would be compatible with an original iPhone, from what I can tell.

If you buy an iPhone from Apple and replace the screen with a third-party one from China, does that make your device a counterfeit? What if you assemble an iPhone entirely out of aftermarket, recycled, or reused parts? The answers to those questions are incredibly important not just for people involved in the repair industry or people who want to fix their own devices, but it’s integral to our understanding of who our devices actually belong to. So maybe this phone isn’t Apple’s iPhone X, but it is an iPhone X.

Solve Motherboard’s weekly, internet-themed crossword puzzle: Solve the Internet.

READ MORE HERE