Attack inception: Compromised supply chain within a supply chain poses new risks

A new software supply chain attack unearthed by Windows Defender Advanced Threat Protection (Windows Defender ATP) emerged as an unusual multi-tier case. Unknown attackers compromised the shared infrastructure in place between the vendor of a PDF editor application and one of its software vendor partners, making the app’s legitimate installer the unsuspecting carrier of a malicious payload. The attack seemed like just another example of how cybercriminals can sneak in malware using everyday normal processes.

The plot twist: The app vendor’s systems were unaffected. The compromise was traceable instead to a second software vendor that hosted additional packages used by the app during installation. This turned out be an interesting and unique case of an attack involving “the supply chain of the supply chain”.

The attackers monetized the campaign using cryptocurrency miners – going as far as using two variants, for good measure – adding to an expanding list of malware attacks that install coin miners.

We estimate based on evidence from Windows Defender ATP that the compromise was active between January and March 2018 but was very limited in nature. Windows Defender ATP detected suspicious activity on a handful of targeted computers; Automated investigation automatically resolved the attack on these machines.

While the impact is limited, the attack highlighted two threat trends: (1) the escalating frequency of attacks that use software supply chains as threat vector, and (2) the increasing use of cryptocurrency miners as primary means for monetizing malware campaigns.

This new supply chain incident did not appear to involve nation-state attackers or sophisticated adversaries but appears to be instigated by petty cybercriminals trying to profit from coin mining using hijacked computing resources. This is evidence that software supply chains are becoming a risky territory and a point-of-entry preferred even by common cybercriminals.

Hunting down the software supply chain compromise

As with most software supply chain compromises, this new attack was carried out silently. It was one of numerous attacks detected and automatically remediated by Windows Defender ATP on a typical day.

While customers were immediately protected, our threat hunting team began an in-depth investigation when similar infection patterns started emerging across different sets of machines: Antivirus capabilities in Windows Defender ATP was detecting and blocking a coin mining process masquerading as pagefile.sys, which was being launched by a service named xbox-service.exe. Windows Defender ATP’s alert timeline showed that xbox-service.exe was installed by an installer package that was automatically downloaded from a suspicious remote server.

Figure 1. Windows Defender ATP alert for the coin miner used in this incident

A machine compromised with coin miner malware is relatively easy to remediate. However, investigating and finding the root cause of the coin miner infection without an advanced endpoint detection and response (EDR) solution like Windows Defender ATP is challenging; tracing the infection requires a rich timeline of events. In this case, Advanced hunting capabilities in Windows Defender ATP can answer three basic questions:

- What created xbox-service.exe and pagefile.sys files on the host?

- Why is xbox-service.exe being launched as a service with high privileges?

- What network and process activities were seen just before xbox-service.exe was launched?

Answering these questions is painless with Windows Defender ATP. Looking at the timeline of multiple machines, our threat hunting team was able to confirm that an offending installer package (MSI) was downloaded and written onto devices through a certain PDF editor app (an alternative app to Adobe Acrobat Reader).

The malicious MSI file was installed silently as part of a set of font packages; it was mixed in with other legitimate MSI files downloaded by the app during installation. All the MSI files were clean and digitally signed by the same legitimate company – except for the one malicious file. Clearly, something in the download and installation chain was subverted at the source, an indication of software supply chain attack.

Figure 2. Windows Defender ATP answers who, when, what (xbox-service.exe created right after MSI installation)

As observed in previous supply chain incidents, hiding malicious code inside an installer or updater program gives attackers the immediate benefit of having full elevated privileges (SYSTEM) on a machine. This gives malicious code the permissions to make system changes like copying files to the system folder, adding a service, and running coin mining code.

Confident with the results of our investigation, we reported findings to the vendor distributing the PDF editor app. They were unaware of the issue and immediately started investigating on their end.

Working with the app vendor, we discovered that the vendor itself was not compromised. Instead, the app vendor itself was the victim of a supply chain attack traceable to their dependency on a second software vendor that was responsible for creating and distributing the additional font packages used by the app. The app vendor promptly notified their partner vendor, who was able to identify and remediate the issue and quickly interrupted the attack.

Multi-tier software supply chain attack

The goal of the attackers was to install a cryptocurrency miner on victim machines. They used the PDF editor app to download and deliver the malicious payload. To compromise the software distribution chain, however, they targeted one of the app vendor’s software partners, which provided and hosted additional font packages downloaded during the app’s installation.

Figure 3. Diagram of the software distribution infrastructure of the two vendors involved in this software supply chain attack

This software supply chain attack shows how cybercriminals are increasingly using methods typically associated with sophisticated cyberattacks. The attack required a certain level of reconnaissance: the attackers had to understand how the normal installation worked. They eventually found an unspecified weakness in the interactions between the app vendor and partner vendor that created an opportunity.

The attackers figured out a way to hijack the installation chain of the MSI font packages by exploiting the weakness they found in the infrastructure. Thus, even if the app vendor was not compromised and was completely unaware of the situation, the app became the unexpected carrier of the malicious payload because the attackers were able to redirect downloads.

At a high level, here’s an explanation of the multi-tier attack:

- Attackers recreated the software partner’s infrastructure on a replica server that the attackers owned and controlled. They copied and hosted all MSI files, including font package, all clean and digitally signed, in the replica sever.

- The attackers decompiled and modified one MSI file, an Asian fonts pack, to add the malicious payload with the coin mining code. With this package tampered with, it is no longer trusted and signed.

- Using an unspecified weakness (which does not appear to be MITM or DNS hijack), the attackers were able to influence the download parameters used by the app. The parameters included a new download link that pointed to the attacker server.

- As a result, for a limited period, the link used by the app to download MSI font packages pointed to a domain name registered with a Ukrainian registrar in 2015 and pointing to a server hosted on a popular cloud platform provider. The app installer from the app vendor, still legitimate and not compromised, followed the hijacked links to the attackers’ replica server instead of the software partner’s server.

While the attack was active, when the app reached out to the software partner’s server during installation, it was redirected to download the malicious MSI font package from the attacker’s replica server. Thus, users who downloaded and installed the app also eventually installed the coin miner malware. After, when the device restarts, the malicious MSI file is replaced with the original legitimate one, so victims may not immediately realize the compromise happened. Additionally, the update process was not compromised, so the app could properly update itself.

Windows Defender ATP customers were immediately alerted of the suspicious installation activity carried out by the malicious MSI installer and by the coin miner binary, and the threat was automatically remediated.

Figure 4. Windows Defender ATP alert process tree for download and installation of MSI font packages: all legitimate, except for one

Since the compromise involved a second-tier software partner vendor, the attack could potentially expand to customers of other app vendors that share the same software partner. Based on PDF application names hardcoded by the attackers in the poisoned MSI file, we have identified at least six additional app vendors that may be at risk of being redirected to download installation packages from the attacker’s server. While we were not able to find evidence that these other vendors distributed the malicious MSI, the attackers were clearly operating with a broader distribution plot in mind.

Another coin miner malware campaign

The poisoned MSI file contained malicious code in a single DLL file that added a service designed to run a coin mining process. The said malware, detected as Trojan:Win64/CoinMiner, hid behind the name xbox-service.exe. When run, this malware consumed affected machines’ computing resources to mine Monero coins.

Figure 5. Malicious DLL payload extracted from the MSI installer

Another interesting aspect of the DLL payload is that during the malware installation stage, it tries to modify the Windows hosts file so that the infected machine can’t communicate with the update servers of certain PDF apps and security software. This is an attempt to prevent remote cleaning and remediation of affected machines.

Figure 6. Preventing further download of updates from certain PDF app vendors

Inside the DLL, we also found some traces of an alternative form of coin mining: browser scripts. It’s unclear if this code was the attackers’ potential secondary plan or simply a work in progress to add one more way to maximize coin mining opportunities. The DLL contained strings and code that may be used to launch a browser to connect to the popular Coinhive library to mine Monero coins.

Figure 7. Browser-based coin mining script

Software supply chain attacks: A growing industry problem

In early 2017, we discovered operation WilySupply, an attack that compromised a text editor’s software updater to install a backdoor on targeted organizations in the financial and IT sectors. Several weeks later, another supply chain attack made headlines by initiating a global ransomware outbreak. We confirmed speculations that the update process for a tax accounting software popular in Ukraine was the initial infection vector for the Petya ransomware. Later that same year, a backdoored version of CCleaner, a popular freeware tool, was delivered from a compromised infrastructure. Then, in early 2018, we uncovered and stopped a Dofoil outbreak that poisoned a popular signed peer-to-peer application to distribute a coin miner.

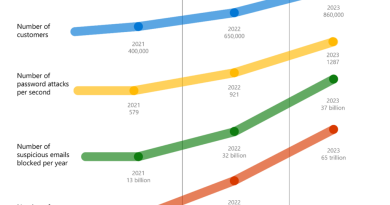

These are just some of many similar cases of supply chain attacks observed in 2017 and 2018. We predict, as many other security researchers do, that this worrisome upward trend will continue.

Figure 8. Software supply chain attacks trends (source: RSA Conference 2018 presentation “The Unexpected Attack Vector: Software Updaters“)

The growing prevalence of supply chain attacks may be partly attributed to hardened modern platforms like Windows 10 and the disappearance of traditional infection vectors like browser exploits. Attackers are constantly looking for the weakest link; with zero-day exploits becoming too expensive to buy or create (exploit kits are at their historically lowest point), attackers search for cheaper alternative entry points like software supply chains compromise. Benefiting from unsafe code practices, unsecure protocols, or unprotected server infrastructure of software vendors to facilitate these attacks.

The benefit for attackers is clear: Supply chains can offer a big base of potential victims and can result in big returns. It’s been observed targeting a wide range of software and impacting organizations in different sectors. It’s an industry-wide problem that requires attention from multiple stakeholders – software developers and vendors who write the code, system admins who manage software installations, and the information security community who find these attacks and create solutions to protect against them, among others.

For further reading, including a list of notable supply chain attacks, check out our RSA Conference 2018 presentation on the topic of software supply chain attack trends: “The Unexpected Attack Vector: Software Updaters”.

Recommendations for software vendors and developers

Software vendors and developers need to ensure they produce secure as well as useful software and services. To do that, we recommend:

- Maintain a highly secure build and update infrastructure.

- Immediately apply security patches for OS and software.

- Implement mandatory integrity controls to ensure only trusted tools run.

- Require multi-factor authentication for admins.

- Build secure software updaters as part of the software development lifecycle.

- Require SSL for update channels and implement certificate pinning.

- Sign everything, including configuration files, scripts, XML files, and packages.

- Check for digital signatures, and don’t let the software updater accept generic input and commands.

- Develop an incident response process for supply chain attacks.

- Disclose supply chain incidents and notify customers with accurate and timely information.

Defending corporate networks against supply chain attacks

Software supply chain attacks raise new challenges in security given that they take advantage of common everyday tasks like software installation and update. Given the increasing prevalence of these types of attacks, organizations should investigate the following security solutions:

- Adopt a walled garden ecosystem for devices, especially for critical systems. Windows 10 in S mode is designed to allow only apps installed from the Microsoft Store, ensuring Microsoft-verified security

- Deploy strong code integrity policies. Application control can be used to restrict the applications that users are allowed to run. It also restricts the code that runs in the system core (kernel) and can block unsigned scripts and other forms of untrusted code for customers who can’t fully adopt Windows 10 in S mode.

- Use endpoint detection and response (EDR) solutions. Endpoint detection and response capabilities in Windows Defender ATP can automatically detect and remediate suspicious activities and other post-breach actions, so even when entry vector is stealthy like for software supply chain, Windows Defender ATP can help to detect and contain such incidents sooner.

In supply chain attacks, the actual compromise happens outside the network, but organizations can detect and block malware that arrive through this method. The built-in security technologies in Windows Defender Advanced Threat Protection (Windows Defender ATP) work together to create a unified endpoint security platform. For example, as demonstrated in this investigation, antivirus capabilities detected the coin mining payload. The detection was surfaced on Windows Defender ATP, where automated investigation resolved the attack, protecting customers. The rich alert timeline and advanced hunting capabilities in Windows Defender ATP showed the extent of the software supply chain attack. Through this unified platform, Windows Defender ATP delivers attack surface reduction, next-generation protection, endpoint detection and response, automated investigation and response, and advanced hunting.

Elia Florio

with Lior Ben Porat

Windows Defender ATP Research team

Indicators of compromise (IOCs)

Malicious MSI font packages:

– a69a40e9f57f029c056d817fe5ce2b3a1099235ecbb0bcc33207c9cff5e8ffd0

– ace295558f5b7f48f40e3f21a97186eb6bea39669abcfa72d617aa355fa5941c

– 23c5e9fd621c7999727ce09fd152a2773bc350848aedba9c930f4ae2342e7d09

– 69570c69086e335f4b4b013216aab7729a9bad42a6ce3baecf2a872d18d23038

Malicious DLLs embedded in MSI font packages:

– b306264d6fc9ee22f3027fa287b5186cf34e7fb590d678ee05d1d0cff337ccbf

Coin miner malware:

– fcf64fc09fae0b0e1c01945176fce222be216844ede0e477b4053c9456ff023e (xbox-service.exe)

– 1d596d441e5046c87f2797e47aaa1b6e1ac0eabb63e119f7ffb32695c20c952b (pagefile.sys)

Software supply chain download server:

– hxxp://vps11240[.]hyperhost[.]name/escape/[some_font_package].msi (IP: 91[.]235 [.]129 [.]133)

Command-and-control/coin mining:

– hxxp://data28[.]somee [.]com/data32[.]zip

– hxxp://carma666[.]byethost12 [.]com/32[.]html

Talk to us

Questions, concerns, or insights on this story? Join discussions at the Microsoft community and Windows Defender Security Intelligence.

Follow us on Twitter @WDSecurity and Facebook Windows Defender Security Intelligence.

READ MORE HERE