Breaking down NOBELIUM’s latest early-stage toolset

As we reported in earlier blog posts, the threat actor NOBELIUM recently intensified an email-based attack that it has been operating and evolving since early 2021. We continue to monitor this active attack and intend to post additional details as they become available. In this blog, we highlight four tools representing a unique infection chain utilized by NOBELIUM: EnvyScout, BoomBox, NativeZone, and VaporRage. These tools have been observed being used in the wild as early as February 2021 attempting to gain a foothold on a variety of sensitive diplomatic and government entities.

As part of this blog, Microsoft Threat Intelligence Center (MSTIC) is releasing an appendix of indicators of compromise (IOCs) for the community to better investigate and understand NOBELIUM’s most recent operations. The NOBELIUM IOCs associated with this activity are available in CSV on the MSTIC GitHub. This sophisticated NOBELIUM attack requires a comprehensive incident response to identify, investigate, and respond. Get the latest information and guidance from Microsoft at https://aka.ms/nobelium. We have also outlined related alerts in Microsoft 365 Defender, so that security teams can check to see if activity has been flagged for investigation.

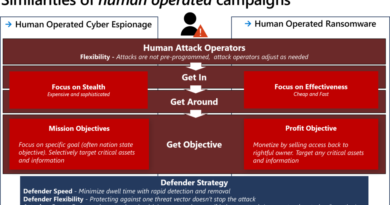

Each of the NOBELIUM tools discussed in this blog is designed for flexibility, enabling the actor to adapt to operational challenges over time. While its technical specifics are not unprecedented, NOBELIUM’s operational security priorities have likely influenced the design of this toolset, which demonstrate preferable features for an actor operating in potentially high-risk and high-visibility environments. These attacker security priorities are:

- Use of trusted channels: BoomBox is a uniquely developed downloader used to obtain a later-stage payload from an actor-controlled Dropbox account. All initial communications leverage the Dropbox API via HTTPS.

- Opportunity for restraint: Consistent with other tools utilized by NOBELIUM, BoomBox, VaporRage, and some variants of NativeZone conduct some level of profiling on an affected system’s environment. MSTIC is currently unaware if these tools benefit from any server-side component. It is plausible that this design may allow NOBELIUM to selectively choose its targets and gain a level of understanding of potential discovery should the implant be run in environments unfamiliar to the actor.

- Ambiguity: VaporRage is a unique shellcode loader seen as the third-stage payload. VaporRage can download, decode, and execute an arbitrary payload fully in-memory. Such design and deployment patterns, which also include staging of payloads on a compromised website, hamper traditional artifacts and forensic investigations, allowing for unique payloads to remain undiscovered.

NOBELIUM is an actor that operates with rapid operational tempo, often leveraging temporary infrastructure, payloads, and methods to obfuscate their activities. We suspect that NOBELIUM can draw from significant operational resources that are often showcased in their periodic campaigns. Since December, the security community has identified a growing collection of payloads attributed to the actor, including the GoldMax, GoldFinder, and Sibot malware identified by Microsoft, as well as TEARDROP (FireEye), SUNSPOT (CrowdStrike), Raindrop (Symantec) and, most recently, FLIPFLOP (Volexity).

Despite growing community visibility since the exposure of the SolarWinds attack in late 2020, NOBELIUM has continued to target government and diplomatic entities across the globe. We anticipate that as these operations progress, NOBELIUM will continue to mature their tools and tactics to target a global audience.

While this post focuses on a single wave of the campaign comprised of the mentioned four malware families, it also highlights variations in the campaign wherein methodologies were altered per wave. The list of indicators in the appendix expands beyond this single wave.

EnvyScout: NV.html (malicious HTML file)

NV.html, tracked by Microsoft as EnvyScout, can be best described as a malicious dropper capable of de-obfuscating and writing a malicious ISO file to disk. EnvyScout is chiefly delivered to targets of NOBELIUM by way of an attachment to spear-phishing emails.

The HTML <body> section of NV.html contains four notable components:

Component #1: Tracking and credential-harvesting URLs

In one variant of EnvyScout, the <body> section contains two URLs, as shown above.

The first, prefixed with a file:// protocol handler, is indicative of an attempt to coax the operating system to send sensitive NTLMv2 material to the specified actor-controlled IP address over port 445. It is likely that the attacker is running a credential capturing service, such as Responder, at the other end of these transactions. Later, brute-forcing of these credentials may result in their exposure.

The second URL, which resolves to the same IP address as the former at the time of analysis, remotely sources an image that is part of the HTML lure. This technique, sometimes referred to as a “web bug”, serves as a read receipt of sorts to NOBELIUM, validating that the prospective target followed through with opening the malicious attachment.

Component #2: FileSaver JavaScript helper code

The second portion of EnvyScout is a modified version of the open-source tool FileSaver, which is intended to assist in the writing of files to disk via JavaScript. The code is borrowed directly from the publicly available variants with minor alterations, including whitespace removal, conversion of hex parameters to decimal, and renamed variables. By combining this code with components #3 and #4 detailed below, NOBELIUM effectively implements a methodology known as HTML smuggling. This methodology may circumvent static analysis of known malicious file types by obscuring them within dynamically altered content upon execution. When combined with dynamic analysis guardrails, this can be an effective way to subvert detections of both types.

Component #3: Obfuscated ISO file

The third section of EnvyScout contains a payload stored as an encoded blob. This payload is decoded by XOR’ng each character with a single-byte key, which then leads to a Base64 payload that is then decoded and written to disk via components #2 and #4.

Component #4: De-obfuscator and dropper script

The final component of EnvyScout is a short code snippet responsible for decoding the ISO in the Base64 encoded/XOR’d blob, and saving it to disk as NV.img with a mime type of “application/octet-stream”. At this stage of infection, the user is expected to open the downloaded ISO, NV.img, by double clicking it.

As Microsoft has been tracking waves of this campaign for months, we have identified various modifications to the actor’s toolkit that were not present in every instance of EnvyScount but are nonetheless notable for defenders:

EnvyScout variation #1:

In some iterations of the actor’s phishing campaigns, EnvyScout contained execution guardrails wherein window.location.pathname was called, and its values were leveraged to ensure that the first two entries in the array of characters returned were “C” and “:”. If this condition was not met—indicating the sample was not being executed from the C: drive—the embedded ISO was not written to disk.

As the attacker had gathered qualities from detonations of previous entries in the campaign via the Firebase fingerprinting JavaScript detailed in a prior blog post, this was assessed to be an execution guardrail to deter analysis and dynamic execution of the samples bearing these guardrails. Having witnessed both iterations of EnvyScout in the wild allows us to infer the intent of some of the information gathered from earlier instances.

EnvyScout variation #2:

In at least one instance of EnvyScout delivery, we observed further enumeration of the executing browser’s environment, wherein the user-agent was used to determine whether a Windows machine received an ISO payload. If the visitor arrived via iOS, they were redirected to external infrastructure.

NV.img (malicious ISO file)

When a target user opens NV.img (dropped by EnvyScout) by double-clicking it, the default behavior on Windows 10 is to mount the ISO image at the next available drive letter. Windows Explorer subsequently displays the contents of the mounted ISO in a window, similar to what users see when they open folders or compressed archives.

As shown above, the mounted ISO contains a single visible file, a shortcut file named NV. However, adjusting the file and folder settings in Windows to show hidden files and folders exposes a hidden folder named NV and a hidden executable named BOOM.exe:

The user is likely expected to interact with NV.lnk, but manual execution of the hidden file BOOM.exe also results in the infection of the system. The individual contents of each file are detailed below.

The use of ISO as a vessel for malicious payloads is further notable due to the lack of mark of the web propagation on the contents, which may impact both host-based detections and reduce friction to user interaction with the contents.

NV.pdf (decoy document)

The hidden NV directory in the mounted ISO contains a decoy PDF file named NV.pdf which contains a decoy advisory:

As described later in this analysis, the contents of the NV directory are displayed to the user by BOOM.exe.

NV.lnk (malicious shortcut)

NV.lnk is a shortcut/launcher for the hidden file BOOM.exe. As shown below, the shortcut leverages a living-off-the-land binary (LOLBin) and technique to proxy the execution of BOOM.exe using the following hardcoded shortcut target value: C:\Windows\System32\rundll32.exe c:\windows\system32\advpack.dll,RegisterOCX BOOM.exe.

Note that Microsoft also saw a variation of this LNK file containing the following shortcut target value: C:\Windows\System32\cmd.exe /c start BOOM.exe.

Numerous other LNKs were identified and are referenced in the appendix linked in this post. Methodologies varied, as did metadata in the LNKs themselves. For instance, the sample with the SHA-256: 48b5fb3fa3ea67c2bc0086c41ec755c39d748a7100d71b81f618e82bf1c479f0 contained a target of “%windir%/system32/explorer.exe Documents.dll,Open”, while the absolute path in the sample was “C:\Windows\system32\rundll32.exe”.

As referenced in Volexity’s blog post on the latest campaign, the LNK metadata was widely removed, and what remained varied between waves. Icons were often folders, meant to trick targets into thinking they were opening a shortcut to a folder.

Microsoft also observed the following targets for known LNK files:

- C:\Windows\System32\rundll32.exe IMGMountingService.dll MountImgHelper

- C:\Windows\System32\rundll32.exe diassvcs.dll InitializeComponent

- C:\Windows\System32\rundll32.exe MsDiskMountService.dll DiskDriveIni

- C:\Windows\system32\rundll32.exe data/mstu.dll,MicrosoftUpdateService

BoomBox: BOOM.exe (malicious downloader)

BOOM.exe, tracked by Microsoft as “BoomBox”, can be best described as a malicious downloader. The downloader is responsible for downloading and executing the next-stage components of the infection. These components are downloaded from Dropbox (using a hardcoded Dropbox Bearer/Access token).

When executed, BoomBox ensures that a directory named NV is present in its current working directory; otherwise it terminates. If the directory is present, BoomBox displays the contents of the NV directory in a new Windows Explorer window (leaving it up to the user to open the PDF file).

Next, BoomBox ensures that the following file is not present on the system (if so, it terminates): %AppData%\Microsoft\NativeCache\NativeCacheSvc.dll (this file is covered later in this analysis). BoomBox performs enumeration of various victim host qualities, such as hostname, domain name, IP address, and username of the victim system to compile the following string (using example values):

Next, BoomBox AES-encrypts the host information string above using the hardcoded encryption key “123do3y4r378o5t34onf7t3o573tfo73” and initialization vector (IV) value “1233t04p7jn3n4rg”. To masquerade the data as contents of a PDF file, BoomBox prepends and appends the magic markers for PDF to the AES-encrypted host information string above:

BoomBox proceeds to upload the data above (masquerading as a PDF file) to a dedicated-per-victim-system folder in Dropbox. For demonstration purposes, an example HTTP(s) POST request used to upload the file/data to Dropbox is included below.

To ensure the file has been successfully uploaded to Dropbox, BoomBox utilizes a set of regular expression values to check the HTTP response from Dropbox. As shown below, the regular expressions are used to check the presence of the is_downloadable, path_lower, content_hash, and size fields (not their values) in the HTTP response received from Dropbox. Notably, BoomBox disregards the outcome of this check and proceeds, even if the upload operation is unsuccessful.

Next, BoomBox downloads an encrypted file from Dropbox. For demonstration purposes, an example HTTP(s) POST request used to download the encrypted file from Dropbox is shown below.

After successfully downloading the encrypted file from Dropbox, BoomBox discards the first 10 bytes from the header and 7 bytes from the footer of the encrypted file, and then AES-decrypts the rest of the file using the hardcoded encryption key “123do3y4r378o5t34onf7t3o573tfo73” and IV value “1233t04p7jn3n4rg”. BoomBox writes the decrypted file to the file system at %AppData%\Microsoft\NativeCache\NativeCacheSvc.dll. It then establishes persistence for NativeCacheSvc.dll by creating a Run registry value named MicroNativeCacheSvc:

HKCU\Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Run\MicroNativeCacheSvc

The Run registry value is populated with the following command, which is used to execute NativeCacheSvc.dll using rundll32.exe and by calling its export function named “_configNativeCache”:

rundll32.exe %AppData%\Microsoft\NativeCache\NativeCacheSvc.dll _configNativeCache

Next, BoomBox downloads a second encrypted file from the Dropbox path /tmp/readme.pdf, discards the first 10 bytes from the header and 7 bytes from the footer of the encrypted file, and then AES-decrypts the rest of the file (using the same AES IV and key as above). It writes the decrypted file at %AppData%\SystemCertificates\CertPKIProvider.dll and proceeds to execute the previously dropped file NativeCacheSvc.dll using the same rundll32.exe command as above.

As the final reconnaissance step, if the system is domain-joined, BoomBox executes an LDAP query to gather data such as distinguished name, SAM account name, email, and display name of all domain users via the filter (&(objectClass=user)(objectCategory=person)).

The enumerated data is AES-encrypted (using the same IV and key as before), encapsulated in a fake PDF file (as previously described), and uploaded to the Dropbox path /new/<Victim_ID>, where <Victim_ID> is the MD5 hash of the victim’s system name, for example: /new/432B65EF29F84E6043A80C15EBA12FD2.

NativeZone: NativeCacheSvc.dll (malicious loader)

NativeCacheSvc.dll, tracked by Microsoft as “NativeZone” can best be described as a malicious loader responsible for utilizing rundll32.exe to load the malicious downloader component CertPKIProvider.dll.

The malicious functionality of NativeCacheSvc.dll is located inside a DLL export named configNativeCache.

As shown above, the export function executes rundll32.exe to load %AppData%\SystemCertificates\Lib\CertPKIProvider.dll by calling its export function named eglGetConfigs.

VaporRage: CertPKIProvider.dll (malicious downloader)

CertPKIProvider.dll, tracked by Microsoft as “VaporRage” can best be described as a shellcode downloader. This version of VaporRage contains 11 export functions including eglGetConfigs, which houses the malicious functionality of the DLL.

As mentioned in the previous section, NativeZone utilizes rundll32.exe to execute the eglGetConfigs export function of CertPKIProvider.dll. Upon execution, the export function first ensures the NativeZone DLL %AppData%\Microsoft\NativeCache\NativeCacheSvc.dll is present on the system (else it terminates). Next, the export function issues an HTTP(s) GET request to a legitimate but compromised WordPress site holescontracting[.]com. The GET request is comprised of the dynamically generated and hardcoded values, for example:

The purpose of the GET request is to first register the system as compromised and then to download an XOR-encoded shellcode blob from the WordPress site (only if the system is of interest to the actor). Once successfully downloaded, the export function XOR decodes the shellcode blob (using a hardcoded multi-byte XOR key “346hrfyfsvvu235632542834”).

It then proceeds to execute the decoded shellcode in memory by jumping to the beginning of the shellcode blob in an executable memory region. The download-decode-execute process is repeated indefinitely, approximately every hour, until the DLL is unloaded from memory. VaporRage can execute any compatible shellcode provided by its C2 server, including a Cobalt Strike stage shellcode.

Additional Custom Cobalt Strike loader from NOBELIUM

As described in a previous blog, NOBELIUM has used multiple custom Cobalt Strike Beacon loaders (likely generated using custom Artifact Kit templates) to enable their malicious activities. These include TEARDROP, Raindrop, and other custom loaders.

Since our last publication, we have identified additional variants of NOBELIUM’s custom Cobalt Strike loaders. Instead of assigning a name to each short-lived and disposable variant, Microsoft will be tracking NOBELIUM’s custom Cobalt Strike loaders and downloaders for the loaders under the name NativeZone. As seen in previous custom NOBELIUM Cobalt Strike loaders, the new loader DLLs also contain decoy export names and function, as well as code and strings borrowed from legitimate applications.

The new NativeZone loaders can be grouped into two variants:

- Variant #1: These loaders embed an encoded/encrypted Cobalt Strike Beacon stage shellcode

- Variant #2: These loaders load an encoded/encrypted Cobalt Strike Beacon stage shellcode from another accompanying file (e.g., an RTF file).

In the succeeding sections, we discuss some of the new NativeZone Cobalt Strike Beacon variants we have observed in our investigation.

NativeZone variant #1

Similar to the previous NOBELIUM custom Cobalt Strike loaders, such as TEARDROP and Raindrop, these NativeZone loaders are responsible for decoding/decrypting an embedded Cobalt Strike Beacon stage shellcode and executing it in memory. Some of the NativeZone loaders feature anti-analysis guardrails to thwart analysis of the samples.

In these versions of NativeZone, the actor has used a variety of encoding and encryption methodologies to obfuscate the embedded shellcode. For example, in the example below, the NativeZone variant uses a simple byte-swap decoding algorithm to decode the embedded shellcode:

Another sample featuring a different decoding methodology to decode the embedded shellcode is shown below:

Another sample, featuring a de-obfuscation methodology leveraging AES encryption algorithm to decrypt the embedded shellcode, is shown below:

Yet another NativeZone sample leveraging AES for decrypting an embedded Cobalt Strike shellcode blob is shown below (note the syntax differences compared to the sample above):

Another sample featuring a different decoding methodology along with leveraging CreateThreadpoolWait() to execute the decoded shellcode blob is below:

Below is an example of anti-analysis technique showing the loader checking if the victim system is a Vmware or VirtualBox VM:

NativeZone variant #2

Unlike variant #1, the NativeZone variant #2 samples do not contain the encoded/encrypted Cobalt Strike Beacon stage shellcode. Instead, these samples read the shellcode from an accompanying file that is shipped with the sample. For example, one NativeZone variant #2 sample was observed alongside an RTF file. The RTF file doubles as both a decoy document and a shellcode carrier file. The RTF file contains the proper RTF file structure and data followed by an encoded shellcode blob (starting at offset 0x658):

When the NativeZone DLL is loaded/executed, it first displays the RTF document to the user.

As mentioned above, the same RTF also contains the encoded Cobalt Strike stage shellcode. As shown below, the NativeZone DLL proceeds to extract the shellcode from the RTF file (starting at file offset 0x658 as shown above), decode the shellcode and execute it on the victim system:

Notes on new and old NOBELIUM PDB paths

The following example PDB paths were observed in the samples analyzed in this blog:

- BoomBox: C:\Users\dev10vs\Desktop\Prog\Obj\BOOM\BOOM\BOOM\obj\Release\BOOM.pdb

- NativeZone: c:\users\devuser\documents\visual studio 2013\Projects\DLL_stageless\Release\DLL_stageless.pdb

- NativeZone: C:\Users\DevUser\Documents\Visual Studio 2013\Projects\DLL_stageless\Release\DLL_stageless.pdb

- NativeZone: C:\Users\dev\Desktop\나타나게 하다\Dll6\x64\Release\Dll6.pdb

Note the presence of ‘dev’ user in the PDB paths above. A ‘dev’ username was previously observed in the PDB path of a NOBELIUM Cobalt Strike loader mentioned in our previous blog: c:\build\workspace\cobalt_cryptor_far (dev071)\farmanager\far\platform.concurrency.hpp.

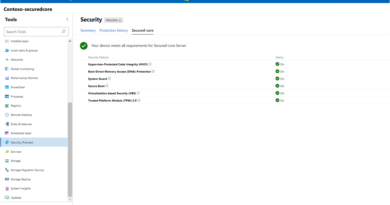

Comprehensive protections for persistence techniques

The sophisticated NOBELIUM attack requires a comprehensive incident response to identify, investigate, and respond. Get the latest information and guidance from Microsoft at https://aka.ms/nobelium.

Microsoft Defender Antivirus

Microsoft Defender Antivirus detects the new NOBELIUM components discussed in this blog as the following malware:

- TrojanDropper:JS/EnvyScout.A!dha

- TrojanDownloader:Win32/BoomBox.A!dha

- Trojan:Win32/NativeZone.A!dha

- Trojan:Win32/NativeZone.B!dha

- Trojan:Win32/NativeZone.C!dha

- Trojan:Win32/NativeZone.D!dha

- TrojanDownloader:Win32/VaporRage.A!dha

Microsoft Defender for Endpoint (EDR)

Alerts with the following titles in the Security Center can indicate threat activity on your network:

- Malicious ISO File used by NOBELIUM

- Cobalt Strike Beacon used by NOBELIUM

- Cobalt Strike network infrastructure used by NOBELIUM

- EnvyScout malware

- BoomBox malware

- NativeZone malware

- VaporRage malware

The following alerts might also indicate threat activity associated with this threat. The below alerts, however, can be triggered by unrelated threat activity and are not monitored in the status cards provided with this report.

- An uncommon file was created and added to startup folder

- A link file (LNK) with unusual characteristics was opened

Azure Sentinel

We have updated the related Azure Sentinel query to include these additional indicators. Azure Sentinel customers can access this query in this GitHub repository.

Indicators of compromise (IOCs)

The NOBELIUM IOCs associated with this activity are available in CSV on the MSTIC GitHub.

READ MORE HERE