Dismantling a fileless campaign: Microsoft Defender ATP next-gen protection exposes Astaroth attack

The prevailing perception about fileless threats, among the security industry’s biggest areas of concern today, is that security solutions are helpless against these supposedly invincible threats. Because fileless attacks run the payload directly in memory or leverage legitimate system tools to run malicious code without having to drop executable files on the disk, they present challenges to traditional file-based solutions.

But let’s set the record straight: being fileless doesn’t mean being invisible; it certainly doesn’t mean being undetectable. There’s no such thing as the perfect cybercrime: even fileless malware leaves a long trail of evidence that advanced detection technologies in Microsoft Defender Advanced Threat Protection (Microsoft Defender ATP) can detect and stop.

To help disambiguate the term fileless, we developed a comprehensive definition for fileless malware as reference for understanding the wide range of fileless threats. We have also discussed at length the advanced capabilities in Microsoft Defender ATP that counter fileless techniques.

I recently unearthed a widespread fileless campaign called Astaroth that completely “lived off the land”: it only ran system tools throughout a complex attack chain. The attack involved multiple steps that use various fileless techniques and proved a great real-world benchmark for Microsoft Defender ATP’s capabilities against fileless threats.

In this blog, I will share my analysis of a fileless attack chain that demonstrates:

- Attackers would go to great lengths to avoid detection

- Advanced technologies in Microsoft Defender ATP next-generation protection expose and defeat fileless attacks

Exposing a fileless info-stealing campaign with Microsoft Defender ATP next-generation protection

I was doing a standard review of telemetry when I noticed an anomaly from a detection algorithm designed to catch a specific fileless technique. Telemetry showed a sharp increase in the use of the Windows Management Instrumentation Command-line (WMIC) tool to run a script (a technique that MITRE refers to XSL Script Processing), indicating a fileless attack.

Figure 1. Windows Defender Antivirus telemetry shows a sudden increase in suspicious activity

After some hunting, I discovered the campaign that aimed to run the Astaroth backdoor directly in memory. Astaroth is a notorious info-stealing malware known for stealing sensitive information like credentials, keystrokes, and other data, which it exfiltrates and sends to a remote attacker. The attacker can then use stolen data to try moving laterally across networks, carry out financial theft, or sell victim information in the cybercriminal underground.

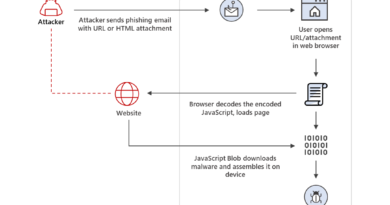

While the behavior may slightly vary in some instances, the attack generally followed these steps: A malicious link in a spear-phishing email leads to an LNK file. When double-clicked, the LNK file causes the execution of the WMIC tool with the “/Format” parameter, which allows the download and execution of a JavaScript code. The JavaScript code in turn downloads payloads by abusing the Bitsadmin tool.

All the payloads are Base64-encoded and decoded using the Certutil tool. Two of them result in plain DLL files (the others remain encrypted). The Regsvr32 tool is then used to load one of the decoded DLLs, which in turn decrypts and loads other files until the final payload, Astaroth, is injected into the Userinit process.

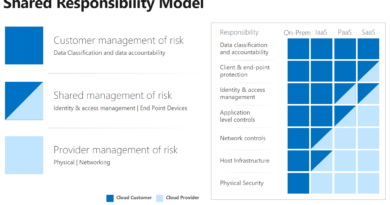

Figure 2. Astaroth “living-off-the-land” attack chain showing multiple legitimate tools abused

It’s interesting to note that at no point during the attack chain is any file run that’s not a system tool. This technique is called living off the land: using legitimate tools that are already present on the target system to masquerade as regular activity.

The attack chain above shows only the Initial Access and Execution stages. In these stages, the attackers used fileless techniques to attempt to silently install the malware on target devices. Astaroth is a notorious information stealer with many other post-breach capabilities that are not discussed in this blog. Preventing the attack in these stages is critical.

Despite its use of “invisible” techniques, the attack chain runs under the scrutiny of Microsoft Defender ATP. Multiple advanced technologies at the core of Microsoft Defender ATP next-generation protection expose these techniques to spot and stop a wide range of attacks.

These protection technologies stop threats at first sight, use the power of the cloud, and leverage Microsoft’s industry-leading optics to deliver effective protection. This defense-in-depth is observed in the way these technologies uncovered and blocked the attack at multiple points in Astaroth’s complex attack chain.

Figure 3. Microsoft Defender ATP solutions for fileless techniques used by Astaroth

For traditional, file-centric antivirus solutions, the only window of opportunity to detect this attack may be when the two DLLs are decoded after being downloaded—after all, every executable used in the attack is non-malicious. If this were the case, this attack would pose a serious problem: since the DLLs use code obfuscation and are likely to change very rapidly between campaigns, focusing on these DLLs would be a vicious trap.

However, as mentioned, next generation protection capabilities in Microsoft Defender ATP catch fileless techniques. Let’s break down the attack steps, enumerate the techniques used using MITRE technique ID as reference, and map the relevant Microsoft Defender ATP protection.

Step 1: Arrival

The victim receives an email with a malicious URL:

![]()

The URL uses misleading names like certidao.htm (Portuguese for “certificate”), abrir_documento.htm (“open document”), pedido.htm (“order”), etc.

When clicked, the malicious link redirects the victim to the ZIP archive certidao.htm.zip, which contains a similarly misleading named LNK file certidao.htm.lnk. When clicked, the LNK file runs an obfuscated BAT command-line.

MITRE techniques observed:

Microsoft Defender ATP next-gen protection defenses:

- Command-line scanning: Trojan:Win32/BadEcho.A

- Heuristics engine: Trojan:Win32/Linkommer.A

- Windows Defender SmartScreen

Step 2: WMIC abuse, part 1

The BAT command runs the system tool WMIC.exe:

The use of the parameter /format causes WMIC to download the file v.txt, which is an XSL file hosted on a legitimate-looking domain. The XSL file hosts an obfuscated JavaScript that is automatically run by WMIC. This JavaScript code simply runs WMIC again.

MITRE techniques observed:

- T1047 – Windows Management Instrumentation

- T1220 – XSL Script Processing

- T1064 – Scripting

- T1027 – Obfuscated Files Or Information

Microsoft Defender ATP next-gen protection defenses:

- Behavior monitoring engine: Behavior:Win32/WmiFormatXslScripting

- AMSI integration engine: Trojan:JS/CovertXslDownload.

Step 3: WMIC abuse, part 2

WMIC is run in a fashion similar to the previous step:

WMIC downloads vv.txt, another XSL file containing an obfuscated JavaScript code, which uses the Bitsadmin, Certutil, and Regsvr32 tools for the next steps.

MITRE techniques observed:

- T1047 – Windows Management Instrumentation

- T1220 – XSL Script Processing

- T1064 – Scripting

- T1027 – Obfuscated Files Or Information

Microsoft Defender ATP next-gen protection defenses:

- Behavior monitoring engine: Behavior:Win32/WmiFormatXslScripting

- Behavior monitoring engine: Behavior:Win32/WmicLoadDll.A

- AMSI integration engine: Trojan:JS/CovertBitsDownload.C

Step 4: Bitsadmin abuse

Multiple instances of Bitsadmin are run to download additional payloads:

The payloads are Base64-encoded and have file names like: falxconxrenwb.~, falxconxrenw64.~, falxconxrenwxa.~, falxconxrenwxb.~, falxconxrenw98.~, falxconxrenwgx.gif, falxfonxrenwg.gif.

MITRE techniques observed:

Microsoft Defender ATP next-gen protection defenses:

- Behavior monitoring engine: Behavior:Win32/WmicBits.A

Step 5: Certutil abuse

The Certutil system tool is used to decode the downloaded payloads:

Only a couple of files are decoded to a DLL; most are still encrypted/obfuscated.

MITRE technique observed:

- T1140 – Deobfuscate/Decode Files Or Information

Microsoft Defender ATP next-gen protection defenses:

- Behavior monitoring engine: Behavior:Win32/WmiCertutil.A

Step 6: Regsvr32 abuse

One of the decoded payload files (a DLL) is run within the contexct of the Regsvr32 system tool:

![]()

The file falxconxrenw64.~ is a proxy: it loads and runs a second DLL, falxconxrenw98.~, and passes it to a third DLL that is obtained by reading files falxconxrenwxa.~ and falxconxrenwxb.~. The DLL falxconxrenw98.~ then reflectively loads the third DLL.

MITRE techniques observed:

- T1117 – Regsvr32

- T1129 – Execution Through Module Load

- T1140 – Deobfuscate/Decode Files Or Information

Microsoft Defender ATP next-gen protection defenses:

- Behavior monitoring engine: Behavior:Win32/UserinitInject.B

- Attack surface reduction: An attack surface reduction rule detects the loading of a DLL that does not meet the age and prevalence criteria (i.e., a new unknown DLL)

Step 7: Userinit abuse

The newly loaded DLL reads and decrypts the file falxconxrenwgx.gif into a DLL. It runs the system tool userinit.exe into which it injects the decrypted DLL. The file falxconxrenwgx.gif is again a proxy that reads, decrypts, and reflectively loads the DLL falxconxrenwg.gif. This last DLL is the malicious info stealer known as Astaroth.

MITRE techniques observed:

- T1117 – Regsvr32

- T1129 – Execution Through Module Load

- T1140 – Deobfuscate/Decode Files Or Information

Microsoft Defender ATP next-gen protection defenses:

- Behavior monitoring engine: Behavior:Win32/Astaroth.A

- Attack surface reduction: An attack surface reduction rule detects the loading of a DLL that does not meet the age and prevalence criteria (i.e., a new unknown DLL)

Comprehensive protection against fileless attacks with Microsoft Threat Protection

The strength of next-generation protection engines in exposing fileless techniques add to the capabilities of the unified endpoint protection platform, Microsoft Defender ATP. Activities related to fileless techniques are reported in Microsoft Defender Security Center as alerts, so security operations teams can further investigate and respond to attacks using endpoint detection and response, advanced hunting, and other capabilities in Microsoft Defender ATP.

Figure 4. Details of Windows Defender Antivirus detections of fileless techniques and malware reported in Microsoft Defender Security Center; details also indicate whether threat is remediated, as was the case with the Astaroth attack

The rest of Microsoft Defender ATP’s capabilities beyond next-generation protection enable security operations teams to detect and remediate fileless threats and other attacks. Notably, Microsoft Defender ATP endpoint detection and response (EDR) has strong and durable detections for fileless and living-off-the-land techniques across the entire attack chain.

Figure 5. Alerts in Microsoft Defender Security Center showing detection of fileless techniques by antivirus and EDR capabilities

We also published a threat analytics report on living-off-the-land binaries to help security operations assess organizational security posture and resilience against these threats. New Microsoft Defender ATP services like threat and vulnerability management and Microsoft Threat Experts (managed threat hunting), further assist organizations in defending against fileless threats.

Through signal-sharing and orchestration of threat remediation across Microsoft’s security technologies, these protections are further amplified in Microsoft Threat Protection, Microsoft’s comprehensive security solution for the modern workplace. For this Astaroth campaign, Office 365 Advanced Threat Protection (Office 365 ATP) detects the emails with malicious links that start the infection chain.

Microsoft Threat Protection secures identities, endpoints, email and data, apps, and infrastructure.

Conclusion: Fileless threats are not invisible

To come back to one of my original points in this blog post, being fileless doesn’t mean being invisible; it certainly doesn’t mean being undetectable.

An analogy: Pretend you are transported to the world of H.G. Wells’ The Invisible Man and can render yourself invisible. You think, great, you can walk straight into a bank and steal money. However, you soon realize that things are not as simple as they sound. When you walk out in the open and it’s cold, your breath’s condensation gives away your position; depending on the type of the ground, you can leave visible footmarks; if it’s raining, water splashing on you creates a visible outline. If you manage to get inside the bank, you still make noise that security guards can hear. Motion detection sensors can feel your presence, and infrared cameras can still see your body heat. Even if you can open a safe or a vault, these storage devices may trigger an alert, or someone may simply notice the safe opening. Not to mention that if you somehow manage to grab the money and put them in a bag, people are likely to notice a bag that’s walking itself out of the bank.

Being invisible may help you for some things, but you should not be under the illusion that you are invincible. The same applies to fileless malware: abusing fileless techniques does not put malware beyond the reach or visibility of security software. On the contrary, some of the fileless techniques may be so unusual and anomalous that they draw immediate attention to the malware, in the same way that a bag of money moving by itself would.

Using invisible techniques and being actually invisible are two different things. Using advanced technologies, Microsoft Defender ATP exposes fileless threats like Astaroth before these attacks can cause more damage.

Andrea Lelli

Microsoft Defender ATP Research

Talk to us

Questions, concerns, or insights on this story? Join discussions at the Microsoft Defender ATP community.

Follow us on Twitter @MsftSecIntel.

READ MORE HERE