DNA Testing: What Happens If Your Genetic Data Is Hacked?

By Jenny KleemanFeatures correspondent

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe personal information of millions of people who sent swabs of their DNA to consumer testing services have been leaked in high profile hacks in recent years, leading to questions about how secure that genetic data is.

What is the most personal thing a criminal could ever steal? Your wedding ring? Your phone? What about your genetic code?

In autumn 2023, a hacker called Golem posted on a well-known message board for cybercriminals, announcing a trove of data stolen from 23andMe, one of the biggest names in at-home DNA testing. The company later acknowledged that the hacker had gained access to personal information in 6.9 million of its users’ profiles.

Listen to The Gift

It seemed to be an ethnically targeted attack: Golem boasted about having access to the accounts of people of Ashkenazi Jewish heritage who had sent their DNA to 23andMe, and offered to sell it to whoever was prepared to pay. News began to circulate suggesting the data breach on Friday 6 October 2023 may have even had antisemitic motivations.

A post purportedly from Golem offered for sale “tailored ethnic groupings, individualized data sets, pinpointed origin estimations, haplogroup details, phenotype information, photographs, links to hundreds of potential relatives, and, most crucially, raw data profiles”. There was a graduated pricing scale, ranging from 100 profiles for $1,000 (£790) to 100,000 profiles for $100,000 (£79,000). “On offer are DNA profiles of millions, ranging from the world’s top business magnates to dynasties often whispered about in conspiracies,” the post continued. It has since been deleted.

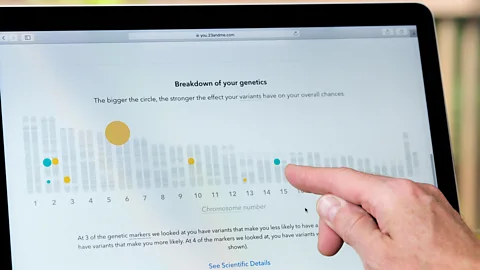

Fourteen million people have spat into a vial and sent their DNA off to 23andMe to be analysed, in search of insights into their ancestry and health. Many do it without thinking too much about what they are giving away: my series investigating the unforeseen consequences of at-home DNA testing for BBC Radio 4 and BBC Sounds is entitled The Gift because we give these kits casually as Christmas and birthday presents. The company’s stated mission is: “To help people access, understand, and benefit from the human genome.”

I took a 23andMe test while recording the series – and it revealed my own Ashkenazi Jewish heritage. But now it seems my data could be part of the package a hacker has been trying to sell for financial benefit. It led me to wonder if information as sensitive as our genetic code can ever be kept safe online.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesData breaches happen all the time, says Brett Callow, a threat analyst with cybersecurity firm Emsisoft. “These incidents are very common and no company is immune,” he says. But genetic information is a very special kind of data: while you can change your passwords, credit card number or bank details if they fall into the hands of a hacker, you can’t change the sequence of your DNA. “When your DNA data gets breached, there is absolutely nothing you can do about it,” says Callow.

The targeting of any group on the basis of what their DNA reveals about their ethnic heritage would be deeply worrying. The potential targeting of individuals with Jewish and Chinese heritage in the 23andMe breach has been raised by a number of leading figures in the US, including the attorney general in Connecticut and a member of the US Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor and Pensions.

The purported ability of Jews to blend in – to “pass” as white – has been at the root of antisemitic conspiracy theories. During the Holocaust, the Nazis forced Jews to wear yellow stars so they could be immediately identifiable. A data breach that included ethnicity estimates given in ancestry reports could mean that Jewish people who had taken a DNA test could potentially have a permanent digital yellow star next to their names, photographs and geographical location.

With the data of half 23andMe’s customers now in the hands of cybercriminals, the breach clearly affected far more than just Ashkenazi Jewish account holders. Indeed, in subsequent posts on the hackers forum, Golem supposedly offered the data of British, German and Chinese 23andMe users, as well as that of 23andMe chief executive Anne Wojcicki, her ex-husband and Google founder Sergey Brin, Elon Musk and members of the British Royal Family.

For Callow, this was never an antisemitic attack. “I don’t believe the attack was motivated racially, ethnically, or anything like that,” he says. “The reference to Jewish people in this post was to attract attention, to get more eyeballs.”

Lily Hay Newman, a writer at Wired focusing on hacking, agrees. “It’s common to try to package and market your data to try to get other criminals to buy it, to make it seem valuable and appealing,” she says.

When news of the 23andMe data breach first broke, the reaction was relatively muted: the attention of Jewish groups was focused on the attacks Hamas had launched on Israel that weekend, and the rise in antisemitic hate incidents in the weeks that followed it. Technology journalists who monitor the hacking forum approached 23andMe for comment, and the company issued a statement. No raw genetic data was leaked, they said, but general categories, such as sex, birth year and genetic ancestry results and geographical location had got into the hands of a so-called “threat actor”.

I asked 23andMe for an interview. They declined to put anyone forward, instead directing me to a blog posted on their website they have been updating since news of the data breach first broke. “The threat actor was able to access less than 0.1%, or roughly 14,000 user accounts, of the existing 14 million 23andMe customers through credential stuffing,” the 23andMe statement said. “That is, usernames and passwords that were used on 23andMe.com were the same as those used on other websites that have been previously compromised or otherwise available.” In other words, the problem was 23andMe customers reusing passwords that hackers had managed to get hold of from other sites.

Credential stuffing is not hacking, in its strictest sense. “It’s attackers using stolen login credentials, like a username and password or an email address and password, to walk in the front door of the account. So really, there’s no hacking required,” says Newman. “But it’s really established that passwords are very difficult for users to manage, and that the blame shouldn’t be on users.”

The 23andMe hack turned out to involve far more than the 14,000 accounts the company initially claimed had been compromised. Once those accounts had been infiltrated, the hacker was able to amass a much larger trove of data through the DNA Relatives feature of 23andMe, which allows account holders to connect with genetic relations. It’s a popular feature – that’s why many people take these tests, after all. In response to inquiries from journalists at TechCrunch in December 2023, 23andMe admitted that in fact the data of 6.9 million users – roughly one out every two people who had sent their DNA to the company – had been breached.

When databases hold very sensitive information, it generally takes more than a single password to access it – think about logging into your online bank account, for example. Most of us are now very used to two-factor verification – which uses an additional step such as a code received in a text message or on an authenticator app – when we use our credit cards or view confidential documents online. But prior to October 2023 this wasn’t a necessary requirement to access an account on 23andMe, even though it held genetic ancestry data coupled with geographical and biographical information.

Yet, it isn’t the first time at-home DNA testing companies have had their databases hacked. In 2018, the email addresses and passwords of over 92 million users of MyHeritage were leaked. The October 2023 23andMe breach, however, was the first time hackers had offered the data for sale. Last year, America’s Federal Trade Commission took action against two direct-to-consumer DNA testing companies, CRI Genetics and 1Health/Vitagene, for failing to keep DNA data secure.

Regardless of the motivation, any breach involving genetic data has potentially wide-ranging consequences. “There is no way of knowing who has access to it now, how many people have access to it, or what they may choose to do with it in the future,” Callow says. “Genetic data does imply health outcomes in a lot of cases, and that is something that may affect a person’s long-term employability or perhaps the likelihood of dying early or suffering a debilitating illness. Potentially, this data could be of interest to employers or insurers.”

Alamy

AlamyIn an age where an increasing number of financial decisions are made by algorithms that scrape all possible sources of information about an individual, there is a serious possibility of financial loss and discrimination arising from a leak of genetic data. Health insurance companies in the US are barred from using genetic information to calculate risk, but there is no federal law to prohibit its use by life insurance companies. It’s easy to imagine a scenario where leaked genetic data might lead to higher premiums or customers being denied cover entirely because of their genes, or being rejected for a long-term bank loan or mortgage because leaked data suggests a higher likelihood of the lender developing Alzheimer’s and passing away before it could be was repaid in full.

23andMe has said the data breach of its user profiles did not include the leaking of raw DNA profiles, but the hacker still had access to ancestry reports that gave ethnicity estimates, geographical location, links to family trees and other personal information. “Any time our personal information is scraped, leaked, hacked, and enters the criminal ecosystem, it fuels identity theft,” says Newman. “Even broad information, geographic information, regional information or things about ethnicity can fuel the customisation of scams to try to trick you.”

23andMe now faces several class action lawsuits in the US as a consequence of the data breach. In January, the company admitted that hackers began infiltrating its customers’ accounts in April 2023, and were able to continue for five months without detection.

“Protecting our customers’ data privacy and security remains a top priority for 23andMe, and we will continue to invest in protecting our systems and data,” the company says. It now requires two-step verification for all customers to access their accounts, and so do its competitors, Ancestry and MyHeritage. None of these companies required it before October 2023.

But researchers have also recently identified other ways in which it might be possible to gather genetic information about people held by consumer genetic services. One paper by scientists at the University of California, Davis, demonstrated it was possible to reconstruct parts of a person’s genome if an “adversary” was to uploading multiple falsified genomes to identify matches with “relatives”.

Even if it were possible to keep data as sensitive as our genetic code safe from hackers, there is no guarantee that once we have consented to share it with a corporation it will remain in their possession. “These companies could be bought – the information could be acquired in that way,” says Callow. In December 2020, New York investment firm Blackstone bought Ancestry, one of 23andMe’s biggest competitors, for $4.7bn (£3.7bn). “Beyond the data, these companies really have very little value,” adds Callow. “They are entirely data driven. Genetic details can now be sold, traded, acquired, along with other corporate intellectual property and assets. The DNA has value, and that value belongs to the company, not to you.”

Blackstone declined an offer to comment when contacted by the BBC.

While the idea of my genes now existing as a corporate asset is somewhat unnerving, I knew what I might be letting myself in for before I sent my DNA to Ancestry and 23andMe. None of the people I spoke to for my BBC series regretted taking an at-home DNA test: the knowledge of who their genes say they are and how they are connected to the world was life changing, and worth any potential risk. Even if you haven’t taken one of these tests, it’s likely that you have a close relative who has, and a very close version of your genetic code may exist in a corporate database.

Your genes may already be out there, in some form. Who knows where they could end up?

* Hacked, a special bonus episode of The Gift, is available on BBC Sounds now, along with the rest of the series. Download them using the podcast app of your choice.

—

If you liked this story, sign up for The Essential List newsletter – a handpicked selection of features, videos and can’t-miss news delivered to your inbox every Friday.

Join one million Future fans by liking us on Facebook, or follow us on Twitter or Instagram.

READ MORE HERE