Gay Dating App Left Private Images, Data Exposed To Web

[Update, Feb. 7, 3:00 PM ET: Ars has confirmed with testing that the private image leak in Jack’d has been closed. A full check of the new app is still in progress.]

Amazon Web Services’ Simple Storage Service powers countless numbers of Web and mobile applications. Unfortunately, many of the developers who build those applications do not adequately secure their S3 data stores, leaving user data exposed—sometimes directly to Web browsers. And while that may not be a privacy concern for some sorts of applications, it’s potentially dangerous when the data in question is “private” photos shared via a dating application.

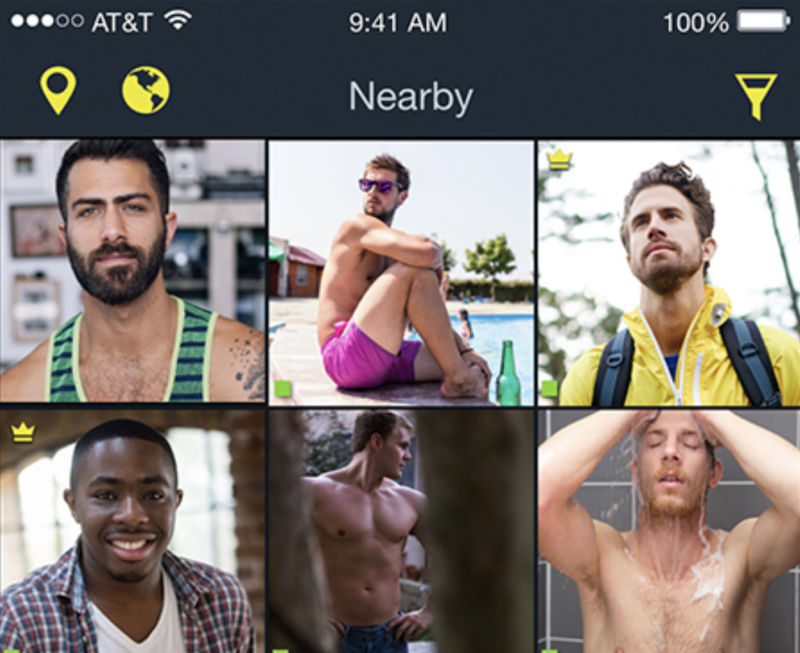

Jack’d, a “gay dating and chat” application with more than 1 million downloads from the Google Play store, has been leaving images posted by users and marked as “private” in chat sessions open to browsing on the Internet, potentially exposing the privacy of thousands of users. Photos were uploaded to an AWS S3 bucket accessible over an unsecured Web connection, identified by a sequential number. By simply traversing the range of sequential values, it was possible to view all images uploaded by Jack’d users—public or private. Additionally, location data and other metadata about users was accessible via the application’s unsecured interfaces to backend data.

The result was that intimate, private images—including pictures of genitalia and photos that revealed information about users’ identity and location—were exposed to public view. Because the images were retrieved by the application over an insecure Web connection, they could be intercepted by anyone monitoring network traffic, including officials in areas where homosexuality is illegal, homosexuals are persecuted, or by other malicious actors. And since location data and phone identifying data were also available, users of the application could be targeted

There’s reason to be concerned. Jack’d developer Online-Buddies Inc.‘s own marketing claims that Jack’d has over 5 million users worldwide on both iOS and Android and that it “consistently ranks among the top four gay social apps in both the App Store and Google Play.” The company, which launched in 2001 with the Manhunt online dating website—”a category leader in the dating space for over 15 years,” the company claims—markets Jack’d to advertisers as “the world’s largest, most culturally diverse gay dating app.”

The bug is fixed in a February 7 update. But the fix comes a year after the leak was first disclosed to the company by security researcher Oliver Hough and more than three months after Ars Technica contacted the company’s CEO, Mark Girolamo, about the issue. Unfortunately, this sort of delay is hardly uncommon when it comes to security disclosures, even when the fix is relatively straightforward. And it points to an ongoing problem with the widespread neglect of basic security hygiene in mobile applications.

Security YOLO

Hough discovered the issues with Jack’d while looking at a collection of dating apps, running them through the Burp Suite Web security testing tool. “The app allows you to upload public and private photos, the private photos they claim are private until you ‘unlock’ them for someone to see,” Hough said. “The problem is that all uploaded photos end up in the same S3 (storage) bucket with a sequential number as the name.” The privacy of the image is apparently determined by a database used for the application—but the image bucket remains public.

Hough set up an account and posted images marked as private. By looking at the Web requests generated by the app, Hough noticed that the image was associated with an HTTP request to an AWS S3 bucket associated with Manhunt. He then checked the image store and found the “private” image with his Web browser. Hough also found that by changing the sequential number associated with his image, he could essentially scroll through images uploaded in the same timeframe as his own.

Hough’s “private” image, along with other images, remained publicly accessible as of February 6, 2018.

There was also data leaked by the application’s API. The location data used by the app’s feature to find people nearby was accessible, as was device identifying data, hashed passwords and metadata about each user’s account. While much of this data wasn’t displayed in the application, it was visible in the API responses sent to the application whenever he viewed profiles.

After searching for a security contact at Online-Buddies, Hough contacted Girolamo last summer, explaining the issue. Girolamo offered to talk over Skype, and then communications stopped after Hough gave him his contact information. After promised follow-ups failed to materialize, Hough contacted Ars in October.

On October 24, 2018, Ars emailed and called Girolamo. He told us he’d look into it. After five days with no word back, we notified Girolamo that we were going to publish an article about the vulnerability—and he responded immediately. “Please don’t I am contacting my technical team right now,” he told Ars. “The key person is in Germany so I’m not sure I will hear back immediately.”

Girolamo promised to share details about the situation by phone, but he then missed the interview call and went silent again—failing to return multiple emails and calls from Ars. Finally, on February 4, Ars sent emails warning that an article would be published—emails Girolamo responded to after being reached on his cell phone by Ars.

Girolamo told Ars in the phone conversation that he had been told the issue was “not a privacy leak.” But when once again given the details, and after he read Ars’ emails, he pledged to address the issue immediately. On February 4, he responded to a follow-up email and said that the fix would be deployed on February 7. “You should [k]now that we did not ignore it—when I talked to engineering they said it would take 3 months and we are right on schedule,” he added.

In the meantime, as we held the story until the issue had been resolved, The Register broke the story—holding back some of the technical details.

Coordinated disclosure is hard

Dealing with the ethics and legalities of disclosure is not new territory for us. When we performed our passive surveillance experiment on an NPR reporter, we had to go through over a month of disclosure with various companies after discovering weaknesses in the security of their sites and products to make sure they were being addressed. But disclosure is a lot harder with organizations that don’t have a formalized way of dealing with it—and sometimes public disclosure through the media seems to be the only way to get action.

It’s hard to tell if Online-Buddies was in fact “on schedule” with a bug fix, given that it was over six months since the initial bug report. It appears only media attention spurred any attempt to fix the issue; it’s not clear whether Ars’ communications or The Register’s publication of the leak had any impact, but the timing of the bug fix is certainly suspicious when viewed in context.

The bigger problem is that this sort of attention can’t scale up to the massive problem of bad security in mobile applications. A quick survey by Ars using Shodan, for example, showed nearly 2,000 Google data stores exposed to public access, and a quick look at one showed what appeared to be extensive amounts of proprietary information just a mouse click away. And so now we’re going through the disclosure process again, just because we ran a Web search.

Five years ago at the Black Hat security conference, In-Q-Tel chief information security officer Dan Geer suggested that the US government should corner the market on zero-day bugs by paying for them and then disclosing them but added that the strategy was “contingent on vulnerabilities being sparse—or at least less numerous.” But vulnerabilities are not sparse, as developers keep adding them to software and systems every day because they keep using the same bad “best” practices.

READ MORE HERE