Hacker Finds He Can Remotely Kill Car Engines After Breaking Into GPS Tracking Apps

A hacker broke into thousands of accounts belonging to users of two GPS tracker apps, giving him the ability to monitor the locations of tens of thousands of vehicles and even turn off the engines for some of them while they were in motion, Motherboard has learned.

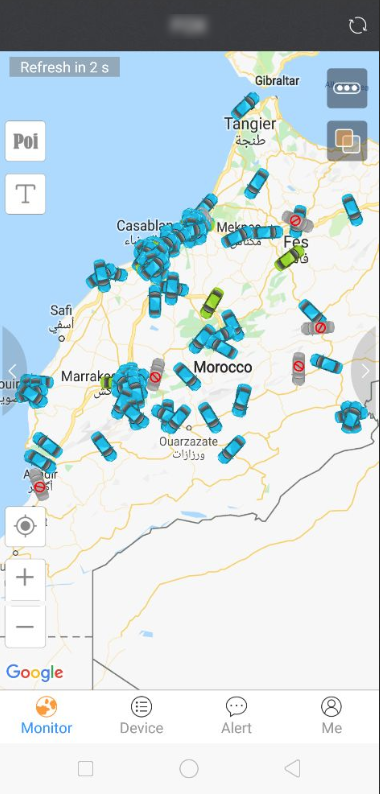

The hacker, who goes by the name L&M, told Motherboard he hacked into more than 7,000 iTrack accounts and more than 20,000 ProTrack accounts, two apps that companies use to monitor and manage fleets of vehicles through GPS tracking devices. The hacker was able to track vehicles in a handful of countries around the world, including South Africa, Morocco, India, and the Philippines. On some cars, the software has the capability of remotely turning off the engines of vehicles that are stopped or are traveling 12 miles per hour or slower, according to the manufacturer of certain GPS tracking devices.

By reverse engineering ProTrack and iTrack’s Android apps, L&M said he realized that all customers are given a default password of 123456 when they sign up.

At that point, the hacker said he brute-forced “millions of usernames” via the apps’ API. Then, he said he wrote a script to attempt to login using those usernames and the default password.

This allowed him to automatically break into thousands of accounts that were using the default password and extract data from them.

Got a tip? You can contact this reporter securely on Signal at +1 917 257 1382, OTR chat at lorenzofb@jabber.ccc.de, or email lorenzofb@motherboard.tv

According to a sample of user data L&M shared with Motherboard, the hacker has scraped a treasure trove of information from ProTrack and iTrack customers, including: name and model of the GPS tracking devices they use, the devices’ unique ID numbers (technically known as an IMEI number); usernames, real names, phone numbers, email addresses, and physical addresses. (According to L&M, he was not able to get all of this information for all users; for some users he was only able to get some of the above information.)

Motherboard was able to confirm the data breach by speaking to four users included in the sample L&M shared with Motherboard, who confirmed that the data provided by the hacker was legitimate.

“My target was the company, not the customers. Customers are at risk because of the company,” L&M told Motherboard in an online chat. “They need to make money, and don’t want to secure their customers.”

A screenshot of the hacked account of a user, provided to Motherboard by the hacker.

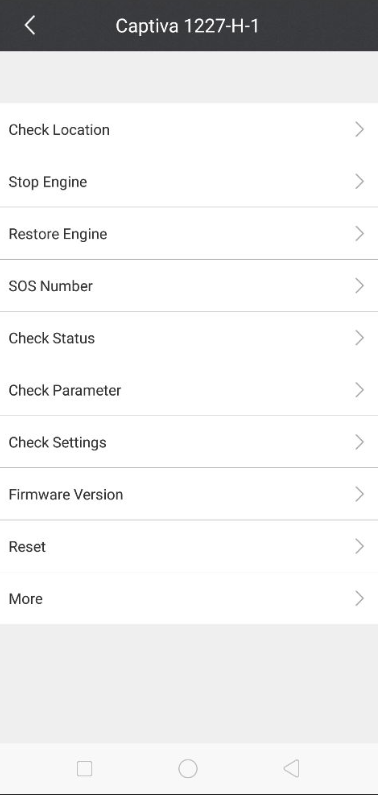

L&M also claimed to be able to do much more than just monitor customers’ vehicles.

“I can absolutely make a big traffic problem all over the world,” L&M said. “I have fully [sic] control hundred of thousands of vehicles, and by one touch, I can stop these vehicles engines.”

Nevertheless, the hacker said he never killed any car’s engine, as that would be too dangerous. Though the hacker didn’t prove that he was able to turn off a car’s engine, a representative for Concox, the makers of one of the hardware GPS tracking devices used by some of the users of ProTrack GPS and iTrack, confirmed to Motherboard that customers can turn off the engines remotely if the vehicles are going under 20 kilometers per hour (around 12 miles per hour.)

The apps have a feature to “stop engine,” according to a screenshot provided by the hacker.

Rahim Luqmaan, the owner of Probotik Systems, a South African company that uses ProTrack, said in a phone call with Motherboard that it’s possible to use ProTrack to stop engines if a technician enables that function when installing the tracking devices.

“That makes it more dangerous,” Luqmaan said about the data breach. “He can actually mess around with […] our clients and customers.”

ProTrack is made by iTryBrand Technology, a company based in Shenzhen, China. iTrack is made by SEEWORLD, a company based in Guangzhou, China. Both iTryBrand and SEEWORLD sell hardware tracking devices and the cloud platforms to manage them directly to users, and to companies that then distribute the hardware and services to users. L&M claimed to have broken into the accounts of some distributors too, which allows him to monitor the vehicles and control the accounts of their customers.

On its Google Play app page, iTrack advertises a free demo account with the username “Demo,” and the password “123456.” ProTrack provides potential customers with a free demo on its website. This week, when Motherboard tried the demo, the site displayed a prompt to change password because “the default password is too simple.” Last week, when Motherboard first tried the demo, this message did not appear. ProTrack’s API, moreover, also mentions the default password of “123456” in its documentation.

Judging from the user interface of both apps, it appears ProTrack and iTrack share the same underlying code.

”He can actually mess around with […] our clients and customers.”

L&M said that ProTrack has reached out to customers via the app and via email to ask them to change their password this week, but it’s not forcing password resets yet.

ProTrack denied the data breach via email, but confirmed that its prompting users to change passwords.

“Our system is working very well and change password is normal way for account security like other systems, any problem?” a company representative said. “What’s more, why you contact our customers for this thing which make them to receive this kind of boring mail. Why hacker contact you?”

iTrack did not immediately respond to an emailed request for comment.

L&M said he contacted the companies asking for a reward. In a screenshot of the response he got from ProTrack, a company representative asked the hacker to give them “a low price.”

“If we pay you, you will give us the tool and will not hack our account again? How can we make sure about this?” the email read. “Sorry for too many questions, this is the first time we meet this disaster.”

The hacker declined to share more on his interactions with the company. But he said he’s got what he wanted.

“They warned after my attack [sic], and that was a success for me. To force them take care about security,” L&M said. “They know now that their customers at risk, So they focused on how to secure their service, a little bit.”

Additional reporting by Joseph Cox

Listen to CYBER, Motherboard’s new weekly podcast about hacking and cybersecurity.

READ MORE HERE