Hackers Infect Multiple Game Developers With Advanced Malware

One of the world’s most prolific hacking groups recently infected several Massively Multiplayer Online game makers, a feat that made it possible for the attackers to push malware-tainted apps to one target’s users and to steal in-game currencies of a second victim’s players.

Researchers from Slovakian security company ESET have tied the attacks to Winnti, a group that has been active since at least 2009 and is believed to have carried out hundreds of mostly advanced attacks. Targets have included Chinese journalists, Uyghur and Tibetan activists, the government of Thailand, and prominent technology organizations. Winnti has been tied to the 2010 hack that stole sensitive data from Google and 34 other companies. More recently, the group has been behind the compromise of the CCleaner distribution platform that pushed malicious updates to millions of people. Winnti carried out a separate supply-chain attack that installed a backdoor on 500,000 ASUS PCs.

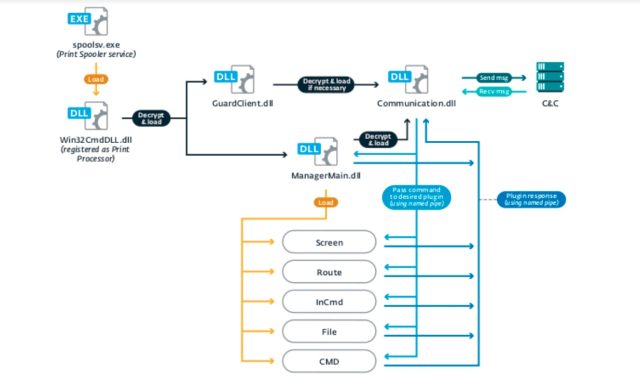

The recent attack used a never-before-seen backdoor that ESET has dubbed PipeMon. To evade security defenses, PipeMon installers bore the imprimatur of a legitimate Windows signing certificate that was stolen from Nfinity Games during a 2018 hack of that gaming developer. The backdoor—which gets its name for the multiple pipes used for one module to communicate with another and the project name of the Microsoft Visual Studio used by the developers—used the location of Windows print processors so it could survive reboots. Nfinity representatives weren’t immediately available to comment.

A strange game

In a post published early Thursday morning, ESET revealed little about the infected companies except to say they included several South Korea- and Taiwan-based developers of MMO games that are available on popular gaming platforms and have thousands of simultaneous players.

“In at least one case, the malware operators compromised a victim’s build system, which could have led to a supply-chain attack, allowing the attackers to trojanize game executables,” ESET researchers wrote. “In another case, the game servers were compromised, which could have allowed the attackers to, for example, manipulate in-game currencies for financial gain.” The researchers said they had no evidence one way or another that either outcome happened.

The ability to gain such deep access to at least two of the latest targets is one testament to the skill of Winnti members. Its theft of the certificate belonging to Nfinity Games during a 2018 supply-chain attack on a different crop of game makers is another. Based on the people and organizations Winnti targets, researchers have tied the group to the Chinese government. Often, the hackers target Internet services and software and game developers with the objective of using any data stolen to better attack the ultimate targets.

Certified fraud

Windows requires certificate signing before software drivers can access the kernel, which is the most security-critical part of any operating system. The certificates—which must be obtained from Windows-trusted authorities after purchasers prove they are providers of legitimate software—can also help to bypass antivirus and other end-point protections. As a result, certificates are frequent plunder in breaches.

Despite the theft coming from a 2018 attack, the certificate owner didn’t revoke it until ESET notified it of the abuse. Tudor Dumitras, co-author of a 2018 paper that studied code certificate compromises, found that it wasn’t unusual to see long delays for revocations, particularly when compared with those of TLS certificates used for websites. With requirements that Web certificates be openly published, it’s much easier to track and identify thefts. Not so with code-signing certificates. Dumitras explained in an email:

This is largely because, unlike the Web PKI, the code-signing PKI is opaque: nobody has visibility into what certificates are currently in use, as the code-signing certificates can be found in executables present on hosts around the world and cannot be collected through Internet-wide scans. This makes it difficult to discover compromised certificates, especially the ones used in targeted attacks. We estimated that even a large AV vendor like Symantec can observe only about 36.5% of the potentially compromised certificates (our paper was published in 2018, before the split of Symantec’s enterprise and customer businesses).

The number of MMO game developers in South Korea and Taiwan is high, and beyond that, there’s no way to know if attackers used their access to actually abuse software builds or game servers. That means there’s little to nothing end users can do to know if they were affected. Given Winnti’s previous successes, the possibility can’t be ruled out.

READ MORE HERE