HTML smuggling surges: Highly evasive loader technique increasingly used in banking malware, targeted attacks

HTML smuggling, a highly evasive malware delivery technique that leverages legitimate HTML5 and JavaScript features, is increasingly used in email campaigns that deploy banking malware, remote access Trojans (RATs), and other payloads related to targeted attacks. Notably, this technique was observed in a spear-phishing campaign from the threat actor NOBELIUM in May. More recently, we have also seen this technique deliver the banking Trojan Mekotio, as well as AsyncRAT/NJRAT and Trickbot, malware that attackers utilize to gain control of affected devices and deliver ransomware payloads and other threats.

As the name suggests, HTML smuggling lets an attacker “smuggle” an encoded malicious script within a specially crafted HTML attachment or web page. When a target user opens the HTML in their web browser, the browser decodes the malicious script, which, in turn, assembles the payload on the host device. Thus, instead of having a malicious executable pass directly through a network, the attacker builds the malware locally behind a firewall.

Figure 1. HTML smuggling overview

This technique is highly evasive because it could bypass standard perimeter security controls, such as web proxies and email gateways, that often only check for suspicious attachments (for example, EXE, ZIP, or DOCX) or traffic based on signatures and patterns. Because the malicious files are created only after the HTML file is loaded on the endpoint through the browser, what some protection solutions only see at the onset are benign HTML and JavaScript traffic, which can also be obfuscated to further hide their true purpose.

Threats that use HTML smuggling bank on the legitimate uses of HTML and JavaScript in daily business operations in their attempt to stay hidden and relevant, as well as challenge organizations’ conventional mitigation procedures. For example, disabling JavaScript could mitigate HTML smuggling created using JavaScript Blobs. However, JavaScript is used to render business-related and other legitimate web pages. In addition, there are multiple ways to implement HTML smuggling through obfuscation and numerous ways of coding JavaScript, making the said technique highly evasive against content inspection. Therefore, organizations need a true “defense in depth” strategy and a multi-layered security solution that inspects email delivery, network activity, endpoint behavior, and follow-on attacker activities.

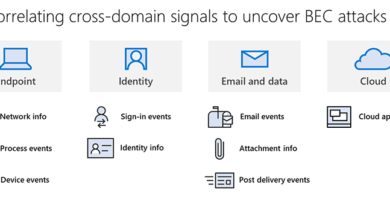

The surge in the use of HTML smuggling in email campaigns is another example of how attackers keep refining specific components of their attacks by integrating highly evasive techniques. Microsoft Defender for Office 365 stops such attacks at the onset using dynamic protection technologies, including machine learning and sandboxing, to detect and block HTML-smuggling links and attachments. Email threat signals from Defender for Office 365 also feed into Microsoft 365 Defender, which provides advanced protection on each domain—email and data, endpoints, identities, and cloud apps—and correlates threat data from these domains to surface evasive, sophisticated threats. This provides organizations with comprehensive and coordinated defense against the end-to-end attack chain.

This blog entry details how HTML smuggling works, provides recent examples of threats and targeted attack campaigns that use it, and enumerates mitigation steps and protection guidance.

How HTML smuggling works

HTML smuggling uses legitimate features of HTML5 and JavaScript, which are both supported by all modern browsers, to generate malicious files behind the firewall. Specifically, HTML smuggling leverages the HTML5 “download” attribute for anchor tags, as well as the creation and use of a JavaScript Blob to put together the payload downloaded into an affected device.

In HTML5, when a user clicks a link, the “download” attribute lets an HTML file automatically download a file referenced in the “href” tag. For example, the code below instructs the browser to download “malicious.docx” from its location and save it into the device as “safe.docx”:

The anchor tag and a file’s “download” attribute also have their equivalents in JavaScript code, as seen below:

The use of JavaScript Blobs adds to the “smuggling” aspect of the technique. A JavaScript Blob stores the encoded data of a file, which is then decoded when passed to a JavaScript API that expects a URL. This means that instead of providing a link to an actual file that a user must manually click to download, the said file can be automatically downloaded and constructed locally on the device using JavaScript codes like the ones below:

Today’s attacks use HTML smuggling in two ways: the link to an HTML smuggling page is included within the email message, or the page itself is included as an attachment. The following section provides examples of actual threats we have recently seen using either of these methods.

Real-world examples of threats using HTML smuggling

HTML smuggling has been used in banking malware campaigns, notably attacks attributed to DEV-0238 (also known as Mekotio) and DEV-0253 (also known as Ousaban), targeting Brazil, Mexico, Spain, Peru, and Portugal. In one of the Mekotio campaigns we’ve observed, attackers sent emails with a malicious link, as shown in the image below.

Figure 2. Sample email used in a Mekotio campaign. Clicking the link starts the HTML smuggling technique.

Figure 3. Threat behavior observed in the Mekotio campaign

In this campaign, a malicious website, hxxp://poocardy[.]net/diretorio/, is used to implement the HTML smuggling technique and drop the malicious downloader file. The image below shows an HTML smuggling page when rendered on the browser.

Figure 4. HTML smuggling page of the Mekotio campaign. Note how the “href” tag references a JavaScript Blob with an octet/stream type to download the malicious ZIP file.

It should be noted that this attack attempt relies on social engineering and user interaction to succeed. When a user clicks the emailed hyperlink, the HTML page drops a ZIP file embedded with an obfuscated JavaScript file.

Figure 5. ZIP file with an obfuscated JavaScript file

When the user opens the ZIP file and executes the JavaScript, the said script connects to hxxps://malparque[.]org/rest/restfuch[.]png and downloads another ZIP file that masquerades as a PNG file. This second ZIP file contains the following files related to DAEMON Tools:

- sptdintf.dll – This is a legitimate file. Various virtual disc applications, including DAEMON Tools and Alcohol 120%, use this dynamic-link library (DLL) file.

- imgengine.dll – This is a malicious file that is either Themida-packed or VMProtected for obfuscation. It accesses geolocation information of the target and attempts credential theft and keylogging.

- An executable file with a random name, which is a renamed legitimate file “Disc Soft Bus Service Pro.” This legitimate file is part of DAEMON Tools Pro and loads both DLLs.

Finally, once the user runs the primary executable (the renamed legitimate file), it launches and loads the malicious DLL via DLL sideloading. As previously mentioned, this DLL file is attributed to Mekotio, a malware family of banking Trojans typically deployed on Windows systems that have targeted Latin American industries since the latter half of 2016.

HTML smuggling in targeted attacks

Beyond banking malware campaigns, various cyberattacks—including more sophisticated, targeted ones—incorporate HTML smuggling in their arsenal. Such adoption shows how tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs) trickle down from cybercrime gangs to malicious threat actors and vice versa. It also reinforces the current state of the underground economy, where such TTPs get commoditized when deemed effective.

For example, in May, Microsoft Threat Intelligence Center (MSTIC) published a detailed analysis of a new sophisticated email attack from NOBELIUM. MSTIC noted that the spear-phishing email used in that campaign contained an HTML file attachment, which, when opened by the targeted user, uses HTML smuggling to download the main payload on the device.

Since then, other malicious actors appeared to have followed NOBELIUM’s suit and adopted the technique for their own campaigns. Between July and August, open-source intelligence (OSINT) community signals showed an uptick in HTML smuggling in campaigns that deliver remote access Trojans (RATs) such as AsyncRAT/NJRAT.

In September, we saw an email campaign that leverages HTML smuggling to deliver Trickbot. Microsoft attributes this Trickbot campaign to an emerging, financially motivated cybercriminal group we’re tracking as DEV-0193.

In the said campaign, the attacker sends a specially crafted HTML page as an attachment to an email message purporting to be a business report.

Figure 6. HTML smuggling page attached in a Trickbot spear-phishing campaign

When the target recipient opens the HTML attachment in a web browser, it constructs a JavaScript file and saves the said file in the device’s default Downloads folder. As an added detection-evasion technique against endpoint security controls, the created JavaScript file is password-protected. Therefore, the user must type the password indicated in the original HTML attachment to open it.

Figure 7. HTML attachment constructs a password-protected downloader JavaScript in the browser

Once the user executes the JavaScript, it initiates a Base64-encoded PowerShell command, which then calls back to the attacker’s servers to download Trickbot.

Figure 8. HTML smuggling attack chain in the Trickbot spear-phishing campaign

Based on our investigations, DEV-0193 targets organizations primarily in the health and education industries, and works closely with ransomware operators, such as those behind the infamous Ryuk ransomware. After compromising an organization, this group acts as a fundamental pivot point and enabler for follow-on ransomware attacks. They also often sell unauthorized access to the said operators. Thus, once this group compromises an environment, it is highly likely that a ransomware attack will follow.

Defending against the wide range of threats that use HTML smuggling

HTML smuggling presents challenges to traditional security solutions. Effectively defending against this stealthy technique requires true defense in depth. It is always better to thwart an attack early in the attack chain—at the email gateway and web filtering level. If the threat manages to fall through the cracks of perimeter security and is delivered to a host machine, then endpoint protection controls should be able to prevent execution.

Microsoft 365 Defender uses multiple layers of dynamic protection technologies, including machine learning-based protection, to defend against malware threats and other attacks that use HTML smuggling at various levels. It correlates threat data from email, endpoints, identities, and cloud apps, providing in-depth and coordinated threat defense. All of these are backed by threat experts who continuously monitor the threat landscape for new attacker tools and techniques.

Microsoft Defender for Office 365 inspects attachments and links in emails to detect and alert on HTML smuggling attempts. Over the past six months, Microsoft blocked thousands of HTML smuggling links and attachments. The timeline graphs below show a spike in HTML smuggling attempts in June and July.

Figure 9. HTML smuggling links detected and blocked

Figure 10. HTML smuggling attachments detected and blocked

Safe Links and Safe Attachments provide real-time protection against HTML smuggling and other email threats by utilizing a virtual environment to check links and attachments in email messages before they are delivered to recipients. Thousands of suspicious behavioral attributes are detected and analyzed in emails to determine a phishing attempt. For example, behavioral rules that check for the following have proven successful in detecting malware-smuggling HTML attachments:

- An attached ZIP file contains JavaScript

- An attachment is password-protected

- An HTML file contains a suspicious script code

- An HTML file decodes a Base64 code or obfuscates a JavaScript

Through automated and threat expert analyses, existing rules are modified, and new ones are added daily.

On endpoints, attack surface reduction rules block or audit activity associated with HTML smuggling. The following rules can help:

- Block JavaScript or VBScript from launching downloaded executable content

- Block execution of potentially obfuscated scripts

- Block executable files from running unless they meet a prevalence, age, or trusted list criterion

Endpoint protection platform (EPP) and endpoint detection and response (EDR) capabilities detect malicious files, malicious behavior, and other related events before and after execution. Advanced hunting, meanwhile, lets defenders create custom detections to proactively find related threats.

Defenders can also apply the following mitigations to reduce the impact of threats that utilize HTML smuggling:

- Prevent JavaScript codes from executing automatically by changing file associations for .js and .jse files.

- Create new Open With parameters in the Group Policy Management Console under User Configuration > Preferences > Control Panel Settings > Folder Options.

- Create parameters for .jse and .js file extensions, associating them with notepad.exe or another text editor.

- Check Office 365 email filtering settings to ensure they block spoofed emails, spam, and emails with malware. Use Microsoft Defender for Office 365 for enhanced phishing protection and coverage against new threats and polymorphic variants. Configure Office 365 to recheck links on click and neutralize malicious messages that have already been delivered in response to newly acquired threat intelligence.

- Check the perimeter firewall and proxy to restrict servers from making arbitrary connections to the internet to browse or download files. Such restrictions help inhibit malware downloads and command and control (C2) activity.

- Encourage users to use Microsoft Edge and other web browsers that support Microsoft Defender SmartScreen, which identifies and blocks malicious websites. Turn on network protection to block connections to malicious domains and IP addresses.

- Turn on cloud-delivered protection and automatic sample submission on Microsoft Defender Antivirus. These capabilities use artificial intelligence and machine learning to quickly identify and stop new and unknown threats.

- Educate users about preventing malware infections. Encourage users to practice good credential hygiene—limit the use of accounts with local or domain admin privileges and turn on Microsoft Defender Firewall to prevent malware infection and stifle propagation.

Learn how you can stop attacks through automated, cross-domain security with Microsoft 365 Defender.

Microsoft 365 Defender Threat Intelligence Team

READ MORE HERE