Human-operated ransomware attacks: A preventable disaster

Human-operated ransomware campaigns pose a significant and growing threat to businesses and represent one of the most impactful trends in cyberattacks today. In these hands-on-keyboard attacks, which are different from auto-spreading ransomware like WannaCry or NotPetya, adversaries employ credential theft and lateral movement methods traditionally associated with targeted attacks like those from nation-state actors. They exhibit extensive knowledge of systems administration and common network security misconfigurations, perform thorough reconnaissance, and adapt to what they discover in a compromised network.

These attacks are known to take advantage of network configuration weaknesses and vulnerable services to deploy devastating ransomware payloads. And while ransomware is the very visible action taken in these attacks, human operators also deliver other malicious payloads, steal credentials, and access and exfiltrate data from compromised networks.

News about ransomware attacks often focus on the downtimes they cause, the ransom payments, and the details of the ransomware payload, leaving out details of the oftentimes long-running campaigns and preventable domain compromise that allow these human-operated attacks to succeed.

Based on our investigations, these campaigns appear unconcerned with stealth and have shown that they could operate unfettered in networks. Human operators compromise accounts with higher privileges, escalate privilege, or use credential dumping techniques to establish a foothold on machines and continue unabated in infiltrating target environments.

Human-operated ransomware campaigns often start with “commodity malware” like banking Trojans or “unsophisticated” attack vectors that typically trigger multiple detection alerts; however, these tend to be triaged as unimportant and therefore not thoroughly investigated and remediated. In addition, the initial payloads are frequently stopped by antivirus solutions, but attackers just deploy a different payload or use administrative access to disable the antivirus without attracting the attention of incident responders or security operations centers (SOCs).

Some well-known human-operated ransomware campaigns include REvil, Samas, Bitpaymer, and Ryuk. Microsoft actively monitors these and other long-running human-operated ransomware campaigns, which have overlapping attack patterns. They take advantage of similar security weaknesses, highlighting a few key lessons in security, notably that these attacks are often preventable and detectable.

Combating and preventing attacks of this nature requires a shift in mindset, one that focuses on comprehensive protection required to slow and stop attackers before they can succeed. Human-operated attacks will continue to take advantage of security weaknesses to deploy destructive attacks until defenders consistently and aggressively apply security best practices to their networks. In this blog, we will highlight case studies of human-operated ransomware campaigns that use different entrance vectors and post-exploitation techniques but have overwhelming overlap in the security misconfigurations they abuse and the devastating impact they have on organizations.

PARINACOTA group: Smash-and-grab monetization campaigns

One actor that has emerged in this trend of human-operated attacks is an active, highly adaptive group that frequently drops Wadhrama as payload. Microsoft has been tracking this group for some time, but now refers to them as PARINACOTA, using our new naming designation for digital crime actors based on global volcanoes.

PARINACOTA impacts three to four organizations every week and appears quite resourceful: during the 18 months that we have been monitoring it, we have observed the group change tactics to match its needs and use compromised machines for various purposes, including cryptocurrency mining, sending spam emails, or proxying for other attacks. The group’s goals and payloads have shifted over time, influenced by the type of compromised infrastructure, but in recent months, they have mostly deployed the Wadhrama ransomware.

The group most often employs a smash-and-grab method, whereby they attempt to infiltrate a machine in a network and proceed with subsequent ransom in less than an hour. There are outlier campaigns in which they attempt reconnaissance and lateral movement, typically when they land on a machine and network that allows them to quickly and easily move throughout the environment.

PARINACOTA’s attacks typically brute forces their way into servers that have Remote Desktop Protocol (RDP) exposed to the internet, with the goal of moving laterally inside a network or performing further brute-force activities against targets outside the network. This allows the group to expand compromised infrastructure under their control. Frequently, the group targets built-in local administrator accounts or a list of common account names. In other instances, the group targets Active Directory (AD) accounts that they compromised or have prior knowledge of, such as service accounts of known vendors.

The group adopted the RDP brute force technique that the older ransomware called Samas (also known as SamSam) infamously used. Other malware families like GandCrab, MegaCortext, LockerGoga, Hermes, and RobbinHood have also used this method in targeted ransomware attacks. PARINACOTA, however, has also been observed to adapt to any path of least resistance they can utilize. For instance, they sometimes discover unpatched systems and use disclosed vulnerabilities to gain initial access or elevate privileges.

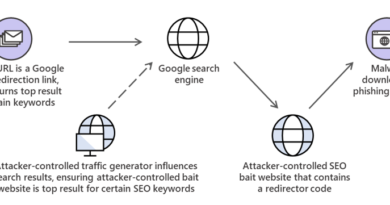

Figure 1. PARINACOTA infection chain

We gained insight into these attacks by investigating compromised infrastructure that the group often utilizes to proxy attacks onto their next targets. To find targets, the group scans the internet for machines that listen on RDP port 3389. The attackers do this from compromised machines using tools like Masscan.exe, which can find vulnerable machines on the entire internet in under six minutes.

Once a vulnerable target is found, the group proceeds with a brute force attack using tools like NLbrute.exe or ForcerX, starting with common usernames like ‘admin’, ‘administrator’, ‘guest’, or ‘test’. After successfully gaining access to a network, the group tests the compromised machine for internet connectivity and processing capacity. They determine if the machine meets certain requirements before using it to conduct subsequent RDP brute force attacks against other targets. This tactic, which has not been observed being used by similar ransomware operators, gives them access to additional infrastructure that is less likely to be blocked. In fact, the group has been observed leaving their tools running on compromised machines for months on end.

On machines that the group doesn’t use for subsequent RDP brute-force attacks, they proceed with a separate set of actions. This technique helps the attackers evade reputation-based detection, which may block their scanning boxes; it also preserves their command-and-control (C2) infrastructure. In addition, PARINACOTA utilizes administrative privileges gained via stolen credentials to turn off or stop any running services that might lead to their detection. Tamper protection in Microsoft Defender ATP prevents malicious and unauthorized to settings, including antivirus solutions and cloud-based detection capabilities.

After disabling security solutions, the group often downloads a ZIP archive that contains dozens of well-known attacker tools and batch files for credential theft, persistence, reconnaissance, and other activities without fear of the next stages of the attack being prevented. With these tools and batch files, the group clears event logs using wevutil.exe, as well as conducts extensive reconnaissance on the machine and the network, typically looking for opportunities to move laterally using common network scanning tools. When necessary, the group elevates privileges from local administrator to SYSTEM using accessibility features in conjunction with a batch file or exploit-laden files named after the specific CVEs they impact, also known as the “Sticky Keys” attack.

The group dumps credentials from the LSASS process, using tools like Mimikatz and ProcDump, to gain access to matching local administrator passwords or service accounts with high privileges that may be used to start as a scheduled task or service, or even used interactively. PARINACOTA then uses the same remote desktop session to exfiltrate acquired credentials. The group also attempts to get credentials for specific banking or financial websites, using findstr.exe to check for cookies associated with these sites.

Figure 2. Microsoft Defender ATP alert for credential theft

With credentials on hand, PARINACOTA establishes persistence using various methods, including:

- Registry modifications using .bat or .reg files to allow RDP connections

- Setting up access through existing remote assistance apps or installing a backdoor

- Creating new local accounts and adding them to the local administrators group

To determine the type of payload to deploy, PARINACOTA uses tools like Process Hacker to identify active processes. The attackers don’t always install ransomware immediately; they have been observed installing coin miners and using massmail.exe to run spam campaigns, essentially using corporate networks as distributed computing infrastructure for profit. The group, however, eventually returns to the same machines after a few weeks to install ransomware.

The group performs the same general activities to deliver the ransomware payload:

- Plants a malicious HTA file (hta in many instances) using various autostart extensibility points (ASEPs), but often the registry Run keys or the Startup folder. The HTA file displays ransom payment instructions.

- Deletes local backups using tools like exe to stifle recovery of ransomed files.

- Stops active services that might interfere with encryption using exe, net.exe, or other tools.

Figure 3. PARINACOTA stopping services and processes

- Drops an array of malware executables, often naming the files based on their intended behavior. If previous attempts to stop antivirus software have been unsuccessful, the group simply drops multiple variants of a malware until they manage to execute one that is not detected, indicating that even when detections and alerts are occurring, network admins are either not seeing them or not reacting to them.

As mentioned, PARINACOTA has recently mostly dropped the Wadhrama ransomware, which leaves the following ransom note after encrypting target files:

Figure 4. Wadhrama ransom note

In several observed cases, targeted organizations that were able to resolve ransomware infections were unable to fully remove persistence mechanisms, allowing the group to come back and deploy ransomware again.

Figure 5. Microsoft Defender ATP machine view showing reinfection by Wadhrama

PARINACOTA routinely uses Monero coin miners on compromised machines, allowing them to collect uniform returns regardless of the type of machine they access. Monero is popular among cybercriminals for its privacy benefits: Monero not only restricts access to wallet balances, but also mixes in coins from other transactions to help hide the specifics of each transaction, resulting in transactions that aren’t as easily traceable by amount as other digital currencies.

As for the ransomware component, we have seen reports of the group charging anywhere from .5 to 2 Bitcoins per compromised machine. This varies depending on what the attackers know about the organization and the assets that they have compromised. The ransom amount is adjusted based on the likelihood the organization will pay due to impact to their company or the perceived importance of the target.

Doppelpaymer: Ransomware follows Dridex

Doppelpaymer ransomware recently caused havoc in several highly publicized attacks against various organizations around the world. Some of these attacks involved large ransom demands, with attackers asking for millions of dollars in some cases.

Doppelpaymer ransomware, like Wadhrama, Samas, LockerGoga, and Bitpaymer before it, does not have inherent worm capabilities. Human operators manually spread it within compromised networks using stolen credentials for privileged accounts along with common tools like PsExec and Group Policy. They often abuse service accounts, including accounts used to manage security products, that have domain admin privileges to run native commands, often stopping antivirus software and other security controls.

The presence of banking Trojans like Dridex on machines compromised by Doppelpaymer point to the possibility that Dridex (or other malware) is introduced during earlier attack stages through fake updaters, malicious documents in phishing email, or even by being delivered via the Emotet botnet.

While Dridex is likely used as initial access for delivering Doppelpaymer on machines in affected networks, most of the same networks contain artifacts indicating RDP brute force. This is in addition to numerous indicators of credential theft and the use of reconnaissance tools. Investigators have in fact found artifacts indicating that affected networks have been compromised in some manner by various attackers for several months before the ransomware is deployed, showing that these attacks (and others) are successful and unresolved in networks where diligence in security controls and monitoring is not applied.

The use of numerous attack methods reflects how attackers freely operate without disruption – even when available endpoint detection and response (EDR) and endpoint protection platform (EPP) sensors already detect their activities. In many cases, some machines run without standard safeguards, like security updates and cloud-delivered antivirus protection. There is also the lack of credential hygiene, over-privileged accounts, predictable local administrator and RDP passwords, and unattended EDR alerts for suspicious activities.

Figure 6. Sample Microsoft Defender ATP alert

The success of attacks relies on whether campaign operators manage to gain control over domain accounts with elevated privileges after establishing initial access. Attackers utilize various methods to gain access to privileged accounts, including common credential theft tools like Mimikatz and LaZange. Microsoft has also observed the use of the Sysinternals tool ProcDump to obtain credentials from LSASS process memory. Attackers might also use LSASecretsView or a similar tool to access credentials stored in the LSA secrets portion of the registry. Accessible to local admins, this portion of the registry can reveal credentials for domain accounts used to run scheduled tasks and services.

Figure 7. Doppelpaymer infection chain

Campaign operators continually steal credentials, progressively gaining higher privileges until they control a domain administrator-level account. In some cases, operators create new accounts and grant Remote Desktop privileges to those accounts.

Apart from securing privileged accounts, attackers use other ways of establishing persistent access to compromised systems. In several cases, affected machines are observed launching a base64-encoded PowerShell Empire script that connects to a C2 server, providing attackers with persistent control over the machines. Limited evidence suggests that attackers set up WMI persistence mechanisms, possibly during earlier breaches, to launch PowerShell Empire.

After obtaining adequate credentials, attackers perform extensive reconnaissance of machines and running software to identify targets for ransomware delivery. They use the built-in command qwinsta to check for active RDP sessions, run tools that query Active Directory or LDAP, and ping multiple machines. In some cases, the attackers target high-impact machines, such as machines running systems management software. Attackers also identify machines that they could use to stay persistent on the networks after deploying ransomware.

Attackers use various protocols or system frameworks (WMI, WinRM, RDP, and SMB) in conjunction with PsExec to move laterally and distribute ransomware. Upon reaching a new device through lateral movement, attackers attempt to stop services that can prevent or stifle successful ransomware distribution and execution. As in other ransomware campaigns, the attackers use native commands to stop Exchange Server, SQL Server, and similar services that can lock certain files and disrupt attempts to encrypt them. They also stop antivirus software right before dropping the ransomware file itself.

Attempts to bypass antivirus protection and deploy ransomware are particularly successful in cases where:

- Attackers already have domain admin privileges

- Tamper protection is off

- Cloud-delivered protection is off

- Antivirus software is not properly managed or is not in a healthy state

Microsoft Defender ATP generates alerts for many activities associated with these attacks. However, in many of these cases, affected network segments and their associated alerts are not actively being monitored or responded to.

Attackers also employ a few other techniques to bypass protections and run ransomware code. In some cases, we found artifacts indicating that they introduce a legitimate binary and use Alternate Data Streams to masquerade the execution of the ransomware binary as legitimate binary.

Figure 8. Command prompt dump output of the Alternate Data Stream

The Doppelpaymer ransomware binary used in many attacks are signed using what appears to be stolen certificates from OFFERS CLOUD LTD, which might be trusted by various security solutions.

Doppelpaymer encrypts various files and displays a ransom note. In observed cases, it uses a custom extension name for encrypted files using information about the affected environment. For example, it has used l33tspeak versions of company names and company phone numbers.

Notably, Doppelpaymer campaigns do not fully infect compromised networks with ransomware. Only a subset of the machines have the malware binary and a slightly smaller subset have their files encrypted. The attackers maintain persistence on machines that don’t have the ransomware and appear intent to use these machines to come back to networks that pay the ransom or do not perform a full incident response and recovery.

Ryuk: Human-operated ransomware initiated from Trickbot infections

Ryuk is another active human-operated ransomware campaign that wreaks havoc on organizations, from corporate entities to local governments to non-profits by disrupting businesses and demanding massive ransom. Ryuk originated as a ransomware payload distributed over email, and but it has since been adopted by human operated ransomware operators.

Like Doppelpaymer, Ryuk is one of possible eventual payloads delivered by human operators that enter networks via banking Trojan infections, in this case Trickbot. At the beginning of a Ryuk infection, an existing Trickbot implant downloads a new payload, often Cobalt Strike or PowerShell Empire, and begins to move laterally across a network, activating the Trickbot infection for ransomware deployment. The use of Cobalt Strike beacon or a PowerShell Empire payload gives operators more maneuverability and options for lateral movement on a network. Based on our investigation, in some networks, this may also provide the added benefit to the attackers of blending in with red team activities and tools.

In our investigations, we found that this activation occurs on Trickbot implants of varying ages, indicating that the human operators behind Ryuk likely have some sort of list of check-ins and targets for deployment of the ransomware. In many cases, however, this activation phase comes well after the initial Trickbot infection, and the eventual deployment of a ransomware payload may happen weeks or even months after the initial infection.

In many networks, Trickbot, which can be distributed directly via email or as a second-stage payload to other Trojans like Emotet, is often considered a low-priority threat, and not remediated and isolated with the same degree of scrutiny as other, more high-profile malware. This works in favor of attackers, allowing them to have long-running persistence on a wide variety of networks. Trickbot, and the Ryuk operators, also take advantage of users running as local administrators in environments and use these permissions to disable security tools that would otherwise impede their actions.

Figure 9. Ryuk infection chain

Once the operators have activated on a network, they utilize their Cobalt Strike or PowerShell tools to initiate reconnaissance and lateral movement on a network. Their initial steps are usually to use built-in commands such as net group to enumerate group membership of high-value groups like domain administrators and enterprise administrators, and to identify targets for credential theft.

Ryuk operators then use a variety of techniques to steal credentials, including the LaZagne credential theft tool. The attackers also save various registry hives to extract credentials from Local Accounts and the LSA Secrets portion of the registry that stores passwords of service accounts, as well as Scheduled Tasks configured to auto start with a defined account. In many cases, services like security and systems management software are configured with privileged accounts, such as domain administrator; this makes it easy for Ryuk operators to migrate from an initial desktop to server-class systems and domain controllers. In addition, in many environments successfully compromised by Ryuk, operators are able to utilize the built-in administrator account to move laterally, as these passwords are matching and not randomized.

Once they have performed initial basic reconnaissance and credential theft, the attackers in some cases utilize the open source security audit tool known as BloodHound to gather detailed information about the Active Directory environment and probable attack paths. This data and associated stolen credentials are accessed by the attacker and likely retained, even after the ransomware portion is ended.

The attackers then continue to move laterally to higher value systems, inspecting and enumerating files of interest to them as they go, possibly exfiltrating this data. The attackers then elevate to domain administrator and utilize these permissions to deploy the Ryuk payload.

The ransomware deployment often occurs weeks or even months after the attackers begin activity on a network. The Ryuk operators use stolen Domain Admin credentials, often from an interactive logon session on a domain controller, to distribute the Ryuk payload. They have been seen doing this via Group Policies, setting a startup item in the SYSVOL share, or, most commonly in recent attacks, via PsExec sessions emanating from the domain controller itself.

Improving defenses to stop human-operated ransomware

In human-operated ransomware campaigns, even if the ransom is paid, some attackers remain active on affected networks with persistence via PowerShell Empire and other malware on machines that may seem unrelated to ransomware activities. To fully recover from human-powered ransomware attacks, comprehensive incident response procedures and subsequent network hardening need to be performed.

As we have learned from the adaptability and resourcefulness of attackers, human-operated campaigns are intent on circumventing protections and cleverly use what’s available to them to achieve their goal, motivated by profit. The techniques and methods used by the human-operated ransomware attacks we discussed in this blog highlight these important lessons in security:

- IT pros play an important role in security

Some of the most successful human-operated ransomware campaigns have been against servers that have antivirus software and other security intentionally disabled, which admins may do to improve performance. Many of the observed attacks leverage malware and tools that are already detected by antivirus. The same servers also often lack firewall protection and MFA, have weak domain credentials, and use non-randomized local admin passwords. Oftentimes these protections are not deployed because there is a fear that security controls will disrupt operations or impact performance. IT pros can help with determining the true impact of these settings and collaborate with security teams on mitigations.

Attackers are preying on settings and configurations that many IT admins manage and control. Given the key role they play, IT pros should be part of security teams.

- Seemingly rare, isolated, or commodity malware alerts can indicate new attacks unfolding and offer the best chance to prevent larger damage

Human-operated attacks involve a fairly lengthy and complex attack chain before the ransomware payload is deployed. The earlier steps involve activities like commodity malware infections and credential theft that Microsoft Defender ATP detects and raises alerts on. If these alerts are immediately prioritized, security operations teams can better mitigate attacks and prevent the ransomware payload. Commodity malware infections like Emotet, Dridex, and Trickbot should be remediated and treated as a potential full compromise of the system, including any credentials present on it.

- Truly mitigating modern attacks requires addressing the infrastructure weakness that let attackers in

Human-operated ransomware groups routinely hit the same targets multiple times. This is typically due to failure to eliminate persistence mechanisms, which allow the operators to go back and deploy succeeding rounds of payloads, as targeted organizations focus on working to resolve the ransomware infections.

Organizations should focus less on resolving alerts in the shortest possible time and more on investigating the attack surface that allowed the alert to happen. This requires understanding the entire attack chain, but more importantly, identifying and fixing the weaknesses in the infrastructure to keep attackers out.

While Wadhrama, Doppelpaymer, Ryuk, Samas, REvil, and other human-operated attacks require a shift in mindset, the challenges they pose are hardly unique.

Removing the ability of attackers to move laterally from one machine to another in a network would make the impact of human-operated ransomware attacks less devastating and make the network more resilient against all kinds of cyberattacks. The top recommendations for mitigating ransomware and other human-operated campaigns are to practice credential hygiene and stop unnecessary communication between endpoints.

Here are relevant mitigation actions that enterprises can apply to build better security posture and be more resistant against cyberattacks in general:

- Harden internet-facing assets and ensure they have the latest security updates. Use threat and vulnerability management to audit these assets regularly for vulnerabilities, misconfigurations, and suspicious activity.

- Secure Remote Desktop Gateway using solutions like Azure Multi-Factor Authentication (MFA). If you don’t have an MFA gateway, enable network-level authentication (NLA).

- Practice the principle of least-privilege and maintain credential hygiene. Avoid the use of domain-wide, admin-level service accounts. Enforce strong randomized, just-in-time local administrator passwords. Use tools like LAPS.

- Monitor for brute-force attempts. Check excessive failed authentication attempts (Windows security event ID 4625).

- Monitor for clearing of Event Logs, especially the Security Event log and PowerShell Operational logs. Microsoft Defender ATP raises the alert “Event log was cleared” and Windows generates an Event ID 1102 when this occurs.

- Turn on tamper protection features to prevent attackers from stopping security services.

- Determine where highly privileged accounts are logging on and exposing credentials. Monitor and investigate logon events (event ID 4624) for logon type attributes. Domain admin accounts and other accounts with high privilege should not be present on workstations.

- Turn on cloud-delivered protection and automatic sample submission on Windows Defender Antivirus. These capabilities use artificial intelligence and machine learning to quickly identify and stop new and unknown threats.

- Turn on attack surface reduction rules, including rules that block credential theft, ransomware activity, and suspicious use of PsExec and WMI. To address malicious activity initiated through weaponized Office documents, use rules that block advanced macro activity, executable content, process creation, and process injection initiated by Office applications Other. To assess the impact of these rules, deploy them in audit mode.

- Turn on AMSI for Office VBA if you have Office 365.

- Utilize the Windows Defender Firewall and your network firewall to prevent RPC and SMB communication among endpoints whenever possible. This limits lateral movement as well as other attack activities.

Figure 10. Improving defenses against human-operated ransomware

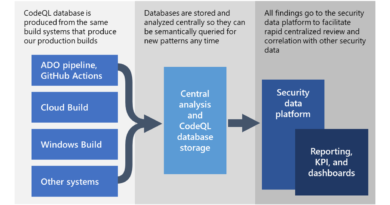

How Microsoft empowers customers to combat human-operated attacks

The rise of adaptable, resourceful, and persistent human-operated attacks characterizes the need for advanced protection on multiple attack surfaces. Microsoft Threat Protection delivers comprehensive protection for identities, endpoints, data, apps, and infrastructure. Through built-intelligence, automation, and integration, Microsoft Threat Protection combines and orchestrates into a single solution the capabilities of Microsoft Defender Advanced Threat Protection (ATP), Office 365 ATP, Azure ATP, and Microsoft Cloud App Security, providing customers integrated security and unparalleled visibility across attack vectors.

Building an optimal organizational security posture is key to defending networks against human-operated attacks and other sophisticated threats. Microsoft Secure Score assesses and measures an organization’s security posture and provides recommended improvement actions, guidance, and control. Using a centralized dashboard in Microsoft 365 security center, organizations can compare their security posture with benchmarks and establish key performance indicators (KPIs).

On endpoints, Microsoft Defender ATP provides unified protection, investigation, and response capabilities. Durable machine learning and behavior-based protections detect human-operated campaigns at multiple points in the attack chain, before the ransomware payload is deployed. These advanced detections raise alerts on the Microsoft Defender Security Center, enabling security operations teams to immediately respond to attacks using the rich capabilities in Microsoft Defender ATP.

The Threat and Vulnerability Management capability uses a risk-based approach to the discovery, prioritization, and remediation of misconfigurations and vulnerabilities on endpoints. Notably, it allows security administrators and IT administrators to collaborate seamlessly to remediate issues. For example, through Microsoft Defender ATP’s integration with Microsoft Intune and System Center Configuration Manager (SCCM), security administrators can create a remediation task in Microsoft Intune with one click.

Microsoft experts have been tracking multiple human operated ransomware groups. To further help customers, we released a Microsoft Defender ATP Threat Analytics report on the campaigns and mitigations against the attack. Through Threat Analytics, customers can see indicators of Wadhrama, Doppelpaymer, Samas, and other campaign activities in their environments and get details and recommendations that are designed to help security operations teams to investigate and respond to attacks. The reports also include relevant advanced hunting queries that can further help security teams look for signs of attacks in their network.

Customers subscribed to Microsoft Threat Experts, the managed threat hunting service in Microsoft Defender ATP, get targeted attack notification on emerging ransomware campaigns that our experts find during threat hunting. The email notifications are designed to inform customers about threats that they need to prioritize, as well as critical information like timeline of events, affected machines, and indicators of compromise, which help in investigating and mitigating attacks. Additionally, with experts on demand, customers can engage directly with Microsoft security analysts to get guidance and insights to better understand, prevent, and respond to human-operated attacks and other complex threats.

Microsoft Threat Protection Intelligence Team

READ MORE HERE