It Was 20 Years Ago Today: Remembering the ILoveYou Virus

The worm infected some 50 million systems worldwide, often rendering them unusable, and cost more than $15 billion to repair.

Today, most security experts view the ILoveYou virus as one of the first, most destructive social-engineering attacks that looked to take advantage of human frailties. But back on May 5, 2000, the day the ILoveYou virus hit hard, such large, worldwide Internet attacks based on malicious emails were uncharted territory.

On that day, Todd Heberlein was an Air Force contractor and was collecting data to find more effective ways to detect and remediate computer worms. In the process, he found fingerprint data that showed nearly 500 Internet connections were impacted with the exact same fingerprint. This virus, soon to be named ILoveYou, moved very fast, and soon the Air Force was on the case.

For those who weren’t in the workforce two decades ago, the ILoveYou virus infected some 50 million systems worldwide – often rendering them unusable – and cost more than $15 billion to repair. It was actually a worm, a malicious program that duplicates itself from one directory, drive computer, or network to another. Most worms spread through email and may have mass-mail functions (such as ILoveYou) that self-propagate via each address in a victim machine’s mailbox.

Twenty years later, Richard Bejtlich also has a clear memory of that day. At the time he was part of the Air Force Computer Emergency Response Team (AFCERT), which responded to ILoveYou.

The Air Force had a unique way of responding to the virus, says Bejtlich, who now is a principal security strategist at Corelight. It leveraged the Automated Security Incident Measurement (ASIM) intrusion-detection system (based on technology Heberlein is credited with developing), which had 144 sensors deployed across 121 Air Force bases worldwide. The ASIM gave the team visibility into email traffic, and it could execute TCP resets to stop incoming email from reaching users’ desktops.

“TCP resets should not be a primary network defense technique, but they worked well enough in our situation to buy time for our mail administrators to act,” Bejtlich recalls. “Also, I don’t use TCP resets today, but in 1998 to 2001 when I was at the AFCERT, they worked well in emergencies. We also used them commercially at a managed security service provider I helped build in 2001/2002.”

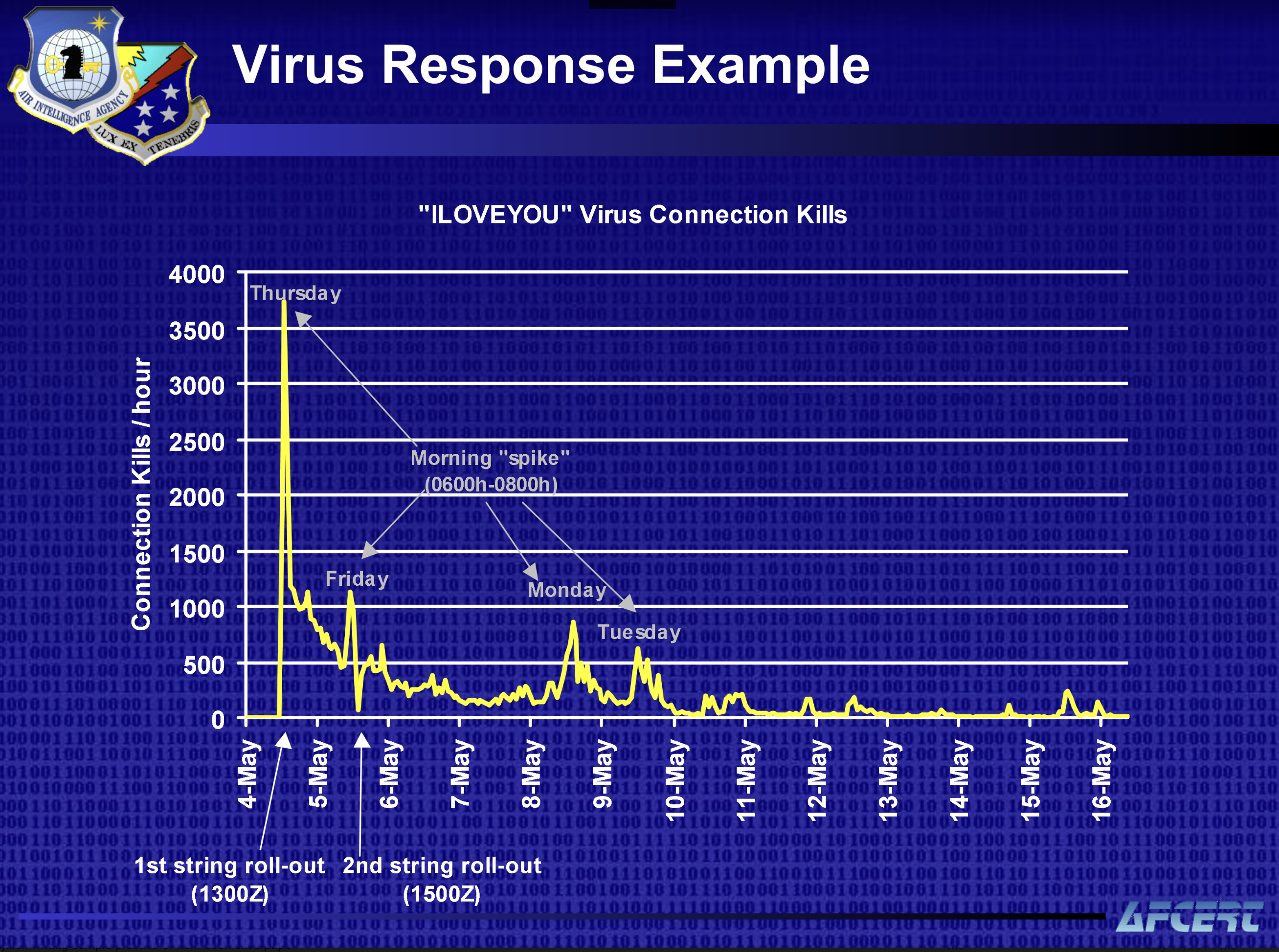

This graph shows the number of TCP reset connections/per hour AFCERT made to counteract the ILoveYou bug when it spiked on May 5, 2000. Note how the virus remained active for a week longer.

The ILoveYou worm wreaked much havoc because it took advantage of the default Visual Basic scripts in Outlook that at the time were easy for users (and in this case, hackers) to access and run. Once ILoveYou entered a user’s email account, it sent itself to every person in the user’s contact list. Recipients would see “ILOVEYOU” in the email’s subject header, with a message that said: “Kindly check the attached LOVELETTER from me.”

The email came with an attachment file named LOVE-LETTER-FOR-YOU.txt.vbs. This virus, along with Melissa a year earlier, were forerunners to other malicious attacks that would attach themselves to simple emails.

“I was in Boston at the time working for Gartner on a healthcare client, and the entire security team was late to our meeting,” recalls John Pescatore, who’s now a director at SANS. “I remember them saying that the ILoveYou worm overwrote their systems, many of which were not backed up, and they lost a lot of data.”

In 2002, following the Melissa virus in 1999, ILoveYou in 2000, and Code Red worm in 2001, Bill Gates declared security Job No. 1 at Microsoft. Pescatore says it took six or seven years for the company to finally improve.

In many ways, Microsoft had little choice. By the late 2000s, Apple had launched the first iPhone and Google had gained traction, so Microsoft had more competition than it had in the 1990s. Plus, the user community was pushing for change. Other developments led to security improvements, too. The first security information and event management systems (SIEMs) were released in the late 1990s and throughout the 2000s, and over the past three to five years more security-conscious developers have entered the workforce who push to build security into products from the time of initial development.

“Remember that SIEMs were a big improvement,” Pescatore says. “In the early days, intrusion detection systems would send out 10,000 alerts, and there was no way to determine what was important. There have been real advances in log management and correlation tools.”

The ILoveYou worm was released in the Philippines by Onel de Guzman, who first introduced the idea as part of his undergraduate thesis. His idea was to release the virus so people who could not afford Internet access could have a free entrée to the Web, an idea that was promptly dismissed by his professors. He was never found guilty of any crimes, largely because no laws against such cybercrimes existed at the time.

Related Content:

Steve Zurier has more than 30 years of journalism and publishing experience, most of the last 24 of which were spent covering networking and security technology. Steve is based in Columbia, Md. View Full Bio

Recommended Reading:

More Insights

Read More HERE