Not only is Zoom’s strong end-to-end encryption not actually end-to-end, its encryption isn’t even that strong

Updated Zoom has faced increased scrutiny and criticism as its usage soared from 10 million users a day to 200 million in a matter of months, all thanks to coronavirus pandemic lockdowns.

Cybersecurity research group Citizen Lab is among those turning the spotlight on the video-conferencing app maker, and on Friday, it published a damning dossier on the state of the software.

The report questions the security of Zoom’s technical infrastructure, claiming the upstart’s network architecture makes it susceptible to pressure for data demands from Chinese authorities.

Zoom in its documentation, and in an in-app display message, has claimed its conferencing service is “end-to-end encrypted,” meaning that an intermediary, include Zoom itself, cannot intercept and decrypt users’ communications as it moves between the sender and receiver.

Zoom’s end-to-end encryption isn’t actually end-to-end at all. Good thing the PM isn’t using it for Cabinet calls. Oh, for f…

When reports emerged that Zoom Meetings are not actually end-to-end encrypted encrypted, Zoom responded that it wasn’t using the commonly accepted definition of the term.

“While we never intended to deceive any of our customers, we recognize that there is a discrepancy between the commonly accepted definition of end-to-end encryption and how we were using it,” the company said in a blog post.

Citizen Lab says it undertook its analysis to clarify conflicting and misleading claims about Zoom’s security because so many businesses, governments, civil society, and healthcare organizations have chosen to use Zoom’s technology – not to mention the British cabinet. According to the company, more than 200 million meeting participants used the service in March.

The Zoom transport protocol, according to the lab’s report, is a custom variant of RTP that encrypts and decrypts the audio and video of Zoom meeting participants with a single AES-128 key that gets shared among all those in the meeting via a TLS-encrypted channel.

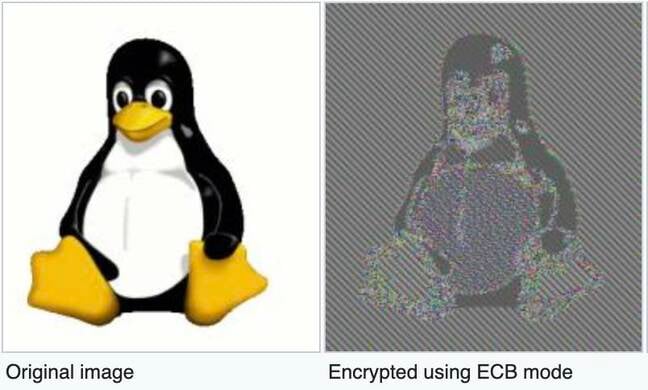

“Zoom’s encryption and decryption use AES in ECB mode, which is well-understood to be a bad idea, because this mode of encryption preserves patterns in the input,” the report says.

Citizen Lab’s visual demonstration that using AES-ECB to encrypt images shared via a Zoom call … Click to enlarge

For streaming media, the SRTP standard should be used in Segmented Integer Counter Mode or f8-mode, according to Citizen Lab. The consequence of not doing so is that an image encrypted using Zoom’s chosen method is still visible.

What’s more, during test calls between two participants in North America, the researchers observed meeting keys being sent via servers in Beijing, China.

“An app with easily-identifiable limitations in cryptography, security issues, and offshore servers located in China which handle meeting keys presents a clear target to reasonably well-resourced nation state attackers, including the People’s Republic of China,” the report says.

Other security researchers have raised concern about Zoom’s technical infrastructure. Dan Ehrlich of Twelve Security, mapped out more than 130,000 subdomains associated with Zoom.us. Many of these, he said, include a number of terms like “face,” “tracking,” and “live,” “reporting,” and “tracking” that should raise questions among users of the software concerned with privacy.

Ehrlich on Friday published a post pointing to Zoom’s ties to universities linked to military hacking activity.

Citizen Lab’s findings add to other concerns about the security of the company’s software and its ability to keep customer data safe.

“As a result of these troubling security issues, we discourage the use of Zoom at this time for use cases that require strong privacy and confidentiality,” the report says.

The Register asked Zoom to comment but we’ve not heard back. Earlier this week, Zoom CEO Eric S. Yuan pledged to deal with the app’s security problems.

For the past week, Zoom has been on the defensive about the security and data practices of its video conferencing app. The company, for instance, removed the Facebook SDK from its iOS app following reports that the app was sending analytics data to Facebook even for users without Facebook accounts.

On Friday, The Washington Post reported that thousands of personal Zoom videos can be viewed by anyone on the web because the company’s file naming scheme is predictable.

Security biz Check Point documented how easy it is to guess Zoom Meeting IDs last year. Now with the global coronavirus health crisis forcing people to participant in video meetings, these IDs don’t even need to be guessed – people post them publicly, making them discoverable through online searches. The result has been trolls intruding on people’s online meetings, a practice that’s come to be known as “zoombombing.”

Also on Friday, Zoom said it “will be placing the Web Client into maintenance mode and take this part of the service offline.” Those who would use the service must now download and install Zoom’s software, known for its dubious use of a pre-installation script. The company has not said how long the web client maintenance will last or why it chose to remove its web app. ®

Updated to add

Zoom claims it routed encryption keys via China because it accidentally added Chinese servers to a list of backend systems intended to be used by non-Chinese users.

Thus, when Zoom applications, being used by folks in America, consulted the list to find a server to connect to, the apps picked machines in China rather than machines outside China. Interesting that Zoom splits its platform into China and non-China…

Sponsored: Webcast: Build the next generation of your business in the public cloud

READ MORE HERE