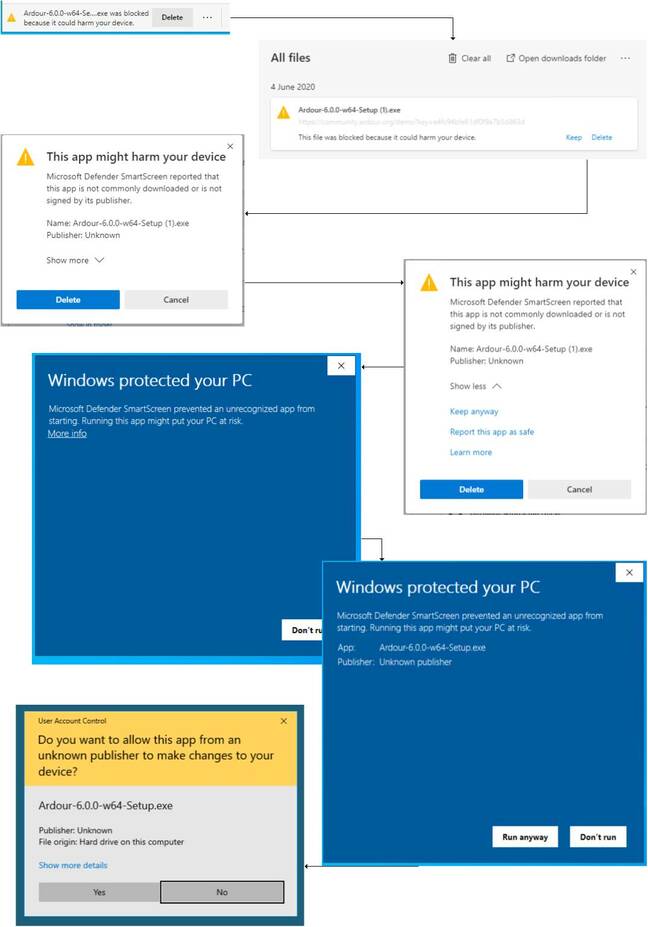

OK Windows 10, we get it: You really do not want us to install this unsigned application. But 7 steps borders on ridiculous

How many times do you have tell Windows that yes, you will install this application?

A developer of a Windows utility has protested that “Microsoft Defender SmartScreen is hurting independent developers” because of the number of warnings and obstacles placed in front of users who download installers that are not signed or sufficiently well known.

Tony Pottier is the developer of ImageView, an alternative to the Windows 10 Photos app for viewing images in a folder. The application is free and open source, but he still has to pay for a code-signing certificate to avoid potential users being put off by warnings when they try to download and install.

Warning or preventing users from installing unverified applications is commonplace in today’s operating systems, but does Windows go too far? We counted seven steps needed to download and install the open-source audio package Ardour 6, which is both unsigned and newly released, using the latest Edge and Windows 10.

The warnings start with the download itself. A message appears at the foot of the browser saying that the installer “was blocked because it could harm your device.” A button to the right says “Delete”. In order to download, a determined user has to go to the full download manager (if they can find it) where there is an option to “Keep”.

That is only the beginning. Next up is a dialog saying “This app might harm your device” with the option to “Delete” or “Cancel.” This is really a dark pattern because if you click “Show more”, it turns out there is another option, “Keep anyway”. “Show different” rather than “Show more”. Click that, and SmartScreen kicks in with another misleading dialog. “Microsoft Defender SmartScreen prevented an unrecognized app from starting. Running this app might put your PC at risk.” The only button says: “Don’t run,” but once again, if you click “More info” you get a revised dialog with the option to “Run anyway.”

After all that, User Account Control kicks in, coloured orange for warning, saying: “Do you want to allow this app from an unknown publisher to make changes to your device?” Only after again clicking “Yes” does the application install. If anything bad happens, you cannot say there was no warning.

Certifiable

It’s a deterrent to installation for sure, but the whole rigmarole can largely be prevented by signing code with a certificate. Certificates for websites are easily obtained for free, but a code-signing certificate has to be purchased; GoDaddy, for example, will sell you one for £111.99 for a year at the time of writing. Pottier calls these “an overpriced piece of prime numbers generated by a computer,” but because they both verify the publisher and show that the code is not tampered with, they make it possible for an application to be identified and trusted.

Pottier says that even the certificate is not enough. SmartScreen also uses a reputation database, and even a signed application starts from zero. Pottier was prevented from submitting an application to the new WinGet repository because it triggered a SmartScreen warning on this basis. It can only win reputation if it is downloaded some unspecified number of times, which is difficult if users are seeing the warnings that put them off.

A better solution is an EV (Extended Validation) code-signing certificate, which are around three times more expensive but appear to be fully trusted by SmartScreen. EV certificates include hardware tokens that are required for signing to reduce the likelihood of compromise. The cost is trivial for commercial or well-sponsored projects, but can be a problem for small developers.

Another open-source package, Inkscape, is also offered for download unsigned. Developer Marc Jeanmougin told us they don’t bother to sign because “on Windows you can usually bypass all warnings.” That said, the installer is signed for the Windows 10 Store and for macOS, where “we don’t really have a choice.”

Windows, as Jeanmougin observed, is relatively permissive despite the plethora of warnings. Apple’s iOS only allows apps to be installed from its curated store. Windows Defender SmartScreen is inconvenient at times but that is less troublesome than a compromised PC. Microsoft is right in that an unsigned application could be tampered with and should not be trusted. If the industry could break the public habit of downloading any old application with a convincing web page wrapped around it, it would be good for security, though this is the not the only route by which malware can enter the system.

That said, the freedom to install software without bureaucracy, approval or extra expense is valued by many PC users and finding the right balance is difficult. It would help if Windows (like Linux on a Chromebook, which runs in a virtual machine) were better protected from badly behaved applications. Windows 10X, perhaps, if and when it reappears. ®

Sponsored: Webcast: Simplify data protection on AWS

READ MORE HERE