Open Source Vulnerabilities database: Nice idea but too many Google-shaped hoops to jump through at present

Hands On Google has big ambitions for its new Open Source Vulnerabilities database, but getting started requires a Google Cloud Platform account and there are other obstacles that may add friction to adoption.

The Chocolate Factory is not happy with the state of open-source software security, which is a big deal not least because its own business and cloud platform depends on open-source code. The company wants to see more discipline and checks in critical open-source software, and revealed that it maintains its own private repositories for many projects to guard against compromised code or newly committed vulnerabilities.

One of the security team’s suggestions was for new ways to manage vulnerability data, including “precise vulnerability metadata from all available data sources.” It also wished for “better tooling… to understand quickly what software is affected by a newly discovered vulnerability.”

The company has now answered the need, or so it hopes, by creating the Open Source Vulnerabilities (OSV) database and API, which lets developers or users of open-source projects query for flaws in the particular version they are using.

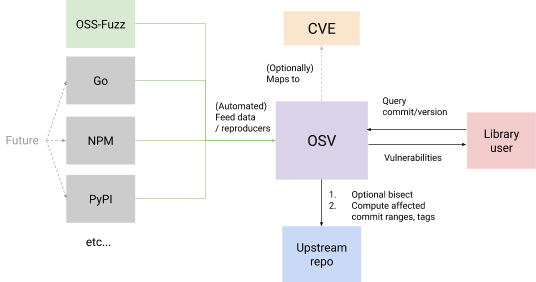

“For each vulnerability, we perform bisects to figure out the exact commit that introduces the bug, as well the exact commit that fixes it,” the docs explain. The database is small at the moment, being mainly based on Google’s own OSS-Fuzz project, which uses fuzzing, deliberately introducing random inputs for the purpose of finding bugs. The project has found more than 25,000 bugs in 275 open-source projects. In fact, Google originally created OSV specifically for OSS-Fuzz and these internal origins are evident in what has now been made public.

A partly aspirational diagram of how Google intends OSV to work once hooked up to more than the in-house OSS-Fuzz project

One of the key features in OSV is the use of bisection, a technique for identifying which change to the code introduced a bug and which one fixed it. Google said that open-source project maintainers “don’t always have the bandwidth to create and publish thorough, accurate information about their vulnerabilities even if they want to.” The idea is that simply providing a test case to OSV that reproduces the bug will be enough to narrow down the precise version of the code that is affected.

Why bother with OSV when we have CVE (Common Vulnerabilities and Exposures), which has 148,882 records, many more than OSV, and is already embedded in the community? “We plan to aggregate existing vulnerabilities feeds (such as CVEs). OSV complements CVEs by extending them with precise vulnerability metadata and making it easier to query for them,” state the docs. Google’s security team considers that “versioning schemes in existing vulnerability standards (such as Common Platform Enumeration (CPE)) do not map well with the actual open source versioning schemes, which are typically versions/tags and commit hashes. The result is missed vulnerabilities that affect downstream consumers.”

It is early days and currently project maintainers cannot even edit or add to details in the database regarding their own code. “We are working on a way for project maintainers to edit relevant OSV vulnerabilities by creating a pull request,” the docs say.

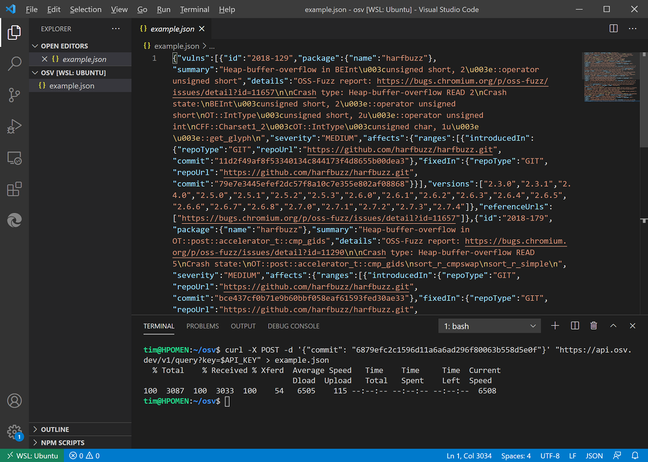

We followed the Getting Started instructions for querying the database, expecting an open API, but immediately landed in a Google-shaped world. In order to run queries, developers have to sign into Google, sign up for Google Cloud Platform, and create a Cloud Platform Project. Next, we had to join a Google Group from the same account, otherwise there is an error when attempting to call the API.

The next step is to create credentials for calling the API and copy the API key that is generated. At this point we had to decide whether to restrict use of the key to specified IP addresses or apps, or whether to allow unrestricted use. Once we had a key, we were able to add the API to the Cloud Platform Project in the same way that would be used for other Google APIs such as Maps, Cloud Vision, Speech to Text, Calendar or Sheets. Developers have to agree to the Google API Terms of Service. Finally, we were able to enable the API and call it with curl, getting details in JSON format of a Chromium bug.

“The API key requirement is an unfortunate requirement but it’s necessary for the higher QPS [Queries per Second] allowed by the API and to prevent abuse,” said Google software engineer Oliver Chang.

The problem with all the above is that the OSV comes across as a Google internal project which happens to be semi-public, rather than something that belongs to the open-source community. It seems curious that the company has not done this in association with the OpenSFF (Open Source Security Foundation), to which it belongs. Requiring users to sign up for Google Cloud Platform and jump through other hoops in order to query the database is not a great way to encourage adoption.

Despite these reservations, the API looks good. Developer tools could use it to answer the specific question: what are the vulnerabilities in the exact versions of the open-source libraries in use by this application? Its usefulness though will depend on attracting broad support, so these early obstacles are unfortunate. ®

READ MORE HERE