Protecting the protector: Hardening machine learning defenses against adversarial attacks

Harnessing the power of machine learning and artificial intelligence has enabled Windows Defender Advanced Threat Protection (Windows Defender ATP) next-generation protection to stop new malware attacks before they can get started – often within milliseconds. These predictive technologies are central to scaling protection and delivering effective threat prevention in the face of unrelenting attacker activity.

Consider this: On a recent typical day, 2.6 million people encountered newly discovered malware in 232 different countries (Figure 1). These attacks were comprised of 1.7 million distinct, first-seen malware and 60% of these campaigns were finished within the hour.

Figure 1. A single day of malware attacks: 2.6M people from 232 countries encountering malware

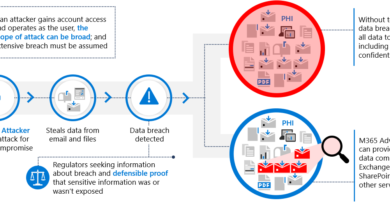

While intelligent, cloud-based approaches represent a sea change in the fight against malware, attackers are not sitting idly by and letting advanced ML and AI systems eat their Bitcoin-funded lunch. If they can find a way to defeat machine learning models at the heart of next-gen AV solutions, even for a moment, they’ll gain the breathing room to launch a successful campaign.

Today at Black Hat USA 2018, in our talk “Protecting the Protector: Hardening Machine Learning Defenses Against Adversarial Attacks”, we presented a series of lessons learned from our experience investigating attackers attempting to defeat our ML and AI protections. We share these lessons in this blog post; we use a case study to demonstrate how these same lessons have hardened Microsoft’s defensive solutions in the real world. We hope these lessons will help provide defensive strategies on deploying ML in the fight against emerging threats.

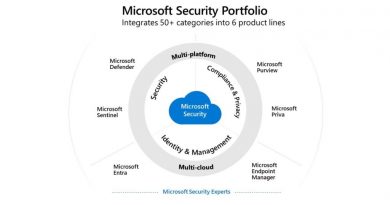

Lesson: Use a multi-layered approach

In our layered ML approach, defeating one layer does not mean evading detection, as there are still opportunities to detect the attack at the next layer, albeit with an increase in time to detect. To prevent detection of first-seen malware, an attacker would need to find a way to defeat each of the first three layers in our ML-based protection stack.

Figure 2. Layered ML protection

Figure 2. Layered ML protection

Even if the first three layers were circumvented, leading to “patient zero” being infected by the malware, the next layers can still uncover the threat and start protecting other users as soon as these layers reach a malware verdict.

Lesson: Leverage the power of the cloud

ML models trained on the backend and shipped to the client are the first (and fastest) layer in our ML-based stack. They come with some drawbacks, not least of which is that an attacker can take the model and apply pressure until it gives up its secrets. This is a very old trick in the malware author’s playbook: iteratively tweak prospective threats and keep scanning it until it’s no longer detected, then unleash it.

Figure 3. Client vs. cloud models

With models hosted in the cloud, it becomes more challenging to brute-force the model. Because the only way to understand what the models may be doing is to keep sending requests to the cloud protection system, such attempts to game the system are “out in the open” and can be detected and mitigated in the cloud.

Lesson: Use a diverse set of models

In addition to having multiple layers of ML-based protection, within each layer we run numerous individual ML models trained to recognize new and emerging threats. Each model has its own focus, or “area of expertise.” Some may focus on a specific file type (for example, PE files, VBA macros, JavaScript, etc.) while others may focus on attributes of a potential threat (for example, behavioral signals, fuzzy hash/distance to known malware, etc.). Different models use different ML algorithms and train on their own unique set of features.

Figure 4. Diversity of machine learning models

Figure 4. Diversity of machine learning models

Each stand-alone model gives its own independent verdict about the likelihood that a potential threat is malware. The diversity, in addition to providing a robust and multi-faceted look at potential threats, offers stronger protection against attackers finding some underlying weakness in any single algorithm or feature set.

Lesson: Use stacked ensemble models

Another effective approach we’ve found to add resilience against adversarial attacks is to use ensemble models. While individual models provide a prediction scoped to a particular area of expertise, we can treat those individual predictions as features to additional “ensemble” machine learning models, combining the results from our diverse set of “base classifiers” to create even stronger predictions that are more resilient to attacks.

In particular, we’ve found that logistic stacking, where we include the individual probability scores from each “base classifier” in the ensemble feature set provides increased effectiveness of malware prediction.

Figure 5. Ensemble machine learning model with individual model probabilities as feature inputs

Figure 5. Ensemble machine learning model with individual model probabilities as feature inputs

As discussed in detail in our Black Hat talk, experimental verification and real-world performance shows this approach helps us resist adversarial attacks. In June, the ensemble models represented nearly 12% of our total malware blocks from cloud protection, which translates into tens of thousands of computers protected by these new models every day.

Figure 6. Blocks by ensemble models vs. other cloud blocks

Figure 6. Blocks by ensemble models vs. other cloud blocks

Case study: Ensemble models vs. regional banking Trojan

“The idea of ensemble learning is to build a prediction model by combining the strengths of a collection of simpler base models.”

— Trevor Hastie, Robert Tibshirani, Jerome Friedman

One of the key advantages of ensemble models is the ability to make a high-fidelity prediction from a series of lower-fidelity inputs. This can sometimes seem a little spooky and counter-intuitive to researchers, but uses cases we’ve studied show this approach can catch malware that the singular models cannot. That’s what happened in early June when a new banking trojan (detected by Windows Defender ATP as TrojanDownloader:VBS/Bancos) targeting users in Brazil was unleashed.

The attack

The attack started with spam e-mail sent to users in Brazil, directing them to download an important document with a name like “Doc062108.zip” inside of which was a “document” that is really a highly obfuscated .vbs script.

Figure 7. Initial infection chain

Figure 7. Initial infection chain

Figure 8. Obfuscated malicious .vbs script

Figure 8. Obfuscated malicious .vbs script

While the script contains several Base64-encoded Brazilian poems, its true purpose is to:

- Check to make sure it’s running on a machine in Brazil

- Check with its command-and-control server to see if the computer has already been infected

- Download other malicious components, including a Google Chrome extension

- Modify the shortcut to Google Chrome to run a different malicious .vbs file

Now whenever the user launches Chrome, this new .vbs malware instead runs.

Figure 9. Modified shortcut to Google Chrome

Figure 9. Modified shortcut to Google Chrome

This new .vbs file runs a .bat file that:

- Kills any running instances of Google Chrome

- Copies the malicious Chrome extension into %UserProfile%\Chrome

- Launches Google Chrome with the “—load-extension=” parameter pointing to the malicious extension

Figure 10. Malicious .bat file that loads the malicious Chrome extension

Figure 10. Malicious .bat file that loads the malicious Chrome extension

With the .bat file’s work done, the user’s Chrome instance is now running the malicious extension.

Figure 11. The installed Chrome extension

Figure 11. The installed Chrome extension

The extension itself runs malicious JavaScript (.js) files on every web page visited.

Figure 12. Inside the malicious Chrome extension

Figure 12. Inside the malicious Chrome extension

The .js files are highly obfuscated to avoid detection:

Figure 13. Obfuscated .js file

Figure 13. Obfuscated .js file

Decoding the hex at the start of the script, we can start to see some clues that this is a banking trojan:

Figure 14. Clues in script show its true intention

Figure 14. Clues in script show its true intention

The .js files detect whether the website visited is a Brazilian banking site. If it is, the POST to the site is intercepted and sent to the attacker’s C&C to gather the user’s login credentials, credit card info, and other info before being passed on to the actual banking site. This activity is happening behind the scenes; to the user, they’re just going about their normal routine with their bank.

Ensemble models and the malicious JavaScript

As the attack got under way, our cloud protection service received thousands of queries about the malicious .js files, triggered by a client-side ML model that considered these files suspicious. The files were highly polymorphic, with every potential victim receiving a unique, slightly altered version of the threat: Figure 15. Polymorphic malware

Figure 15. Polymorphic malware

The interesting part of the story are these malicious JavaScript files. How did our ML models perform detecting these highly obfuscated scripts as malware? Let’s look at one of instances. At the time of the query, we received metadata about the file. Here’s a snippet:

| Report time | 2018-06-14 01:16:03Z |

| SHA-256 | 1f47ec030da1b7943840661e32d0cb7a59d822e400063cd17dc5afa302ab6a52 |

| Client file type model | SUSPICIOUS |

| File name | vNSAml.js |

| File size | 28074 |

| Extension | .js |

| Is PE file | FALSE |

| File age | 0 |

| File prevalence | 0 |

| Path | C:\Users\<user>\Chrome\1.9.6\vNSAml.js |

| Process name | xcopy.exe |

Figure 16 – File metadata sent during query to cloud protection service

Based on the process name, this query was sent when the .bat file copied the .js files into the %UserProfile%\Chrome directory.

Individual metadata-based classifiers evaluated the metadata and provided their probability scores. Ensemble models then used these probabilities, along with other features, to reach their own probability scores:

| Model | Probability that file is malware |

|---|---|

| Fuzzy hash 1 | 0.01 |

| Fuzzy hash 2 | 0.06 |

| ResearcherExpertise | 0.64 |

| Ensemble 1 | 0.85 |

| Ensemble 2 | 0.91 |

Figure 17. Probability scores by individual classifiers

In this case, the second ensemble model had a strong enough score for the cloud to issue a blocking decision. Even though none of the individual classifiers in this case had a particularly strong score, the ensemble model had learned from training on millions of clean and malicious files that this combination of scores, in conjunction with a few other non-ML based features, indicated the file had a very strong likelihood of being malware.

Figure 18. Ensemble models issue a blocking decision

Figure 18. Ensemble models issue a blocking decision

As the queries on the malicious .js files rolled in, the cloud issued blocking decisions within a few hundred milliseconds using the ensemble model’s strong probability score, enabling Windows Defender ATP’s antivirus capabilities to prevent the malicious .js from running and remove it. Here is a map overlay of the actual ensemble-based blocks of the malicious JavaScript files at the time:

Figure 19. Blocks by ensemble model of malicious JavaScript used in the attack

Figure 19. Blocks by ensemble model of malicious JavaScript used in the attack

Ensemble ML models enabled Windows Defender ATP’s next-gen protection to defend thousands of customers in Brazil targeted by the unscrupulous attackers from having a potentially bad day, while ensuring the frustrated malware authors didn’t hit the big pay day they were hoping for. Bom dia.

Further reading on machine learning and artificial intelligence in Windows Defender ATP

Indicators of compromise (IoCs)

- Doc062018.zip (SHA-256: 93f488e4bb25977443ff34b593652bea06e7914564af5721727b1acdd453ced9)

- Doc062018-2.vbs (SHA-256: 7b1b7b239f2d692d5f7f1bffa5626e8408f318b545cd2ae30f44483377a30f81)

- zobXhz.js 1f47(SHA-256: ec030da1b7943840661e32d0cb7a59d822e400063cd17dc5afa302ab6a52)

Randy Treit, Holly Stewart, Jugal Parikh

Windows Defender Research

with special thanks to Allan Sepillo and Samuel Wakasugui

Talk to us

Questions, concerns, or insights on this story? Join discussions at the Microsoft community and Windows Defender Security Intelligence.

Follow us on Twitter @WDSecurity and Facebook Windows Defender Security Intelligence.

READ MORE HERE