Ransomware groups continue to target healthcare, critical services; here’s how to reduce risk

At a time when remote work is becoming universal and the strain on SecOps, especially in healthcare and critical industries, has never been higher, ransomware actors are unrelenting, continuing their normal operations.

Multiple ransomware groups that have been accumulating access and maintaining persistence on target networks for several months activated dozens of ransomware deployments in the first two weeks of April 2020. So far the attacks have affected aid organizations, medical billing companies, manufacturing, transport, government institutions, and educational software providers, showing that these ransomware groups give little regard to the critical services they impact, global crisis notwithstanding. These attacks, however, are not limited to critical services, so organizations should be vigilant for signs of compromise.

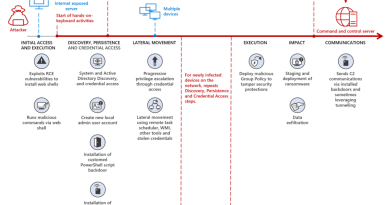

The ransomware deployments in this two-week period appear to cause a slight uptick in the volume of ransomware attacks. However, Microsoft security intelligence as well as forensic data from relevant incident response engagements by Microsoft Detection and Response Team (DART) showed that many of the compromises that enabled these attacks occurred earlier. Using an attack pattern typical of human-operated ransomware campaigns, attackers have compromised target networks for several months beginning earlier this year and have been waiting to monetize their attacks by deploying ransomware when they would see the most financial gain.

Many of these attacks started with the exploitation of vulnerable internet-facing network devices; others used brute force to compromise RDP servers. The attacks delivered a wide range of payloads, but they all used the same techniques observed in human-operated ransomware campaigns: credential theft and lateral movement, culminating in the deployment of a ransomware payload of the attacker’s choice. Because the ransomware infections are at the tail end of protracted attacks, defenders should focus on hunting for signs of adversaries performing credential theft and lateral movement activities to prevent the deployment of ransomware.

In this blog, we share our in-depth analysis of these ransomware campaigns. Below, we will cover:

We have included additional technical details including hunting guidance and recommended prioritization for security operations (SecOps).

Vulnerable and unmonitored internet-facing systems provide easy access to human-operated attacks

While the recent attacks deployed various ransomware strains, many of the campaigns shared infrastructure with previous ransomware campaigns and used the same techniques commonly observed in human-operated ransomware attacks.

In stark contrast to attacks that deliver ransomware via email—which tend to unfold much faster, with ransomware deployed within an hour of initial entry—the attacks we saw in April are similar to the Doppelpaymer ransomware campaigns from 2019, where attackers gained access to affected networks months in advance. They then remained relatively dormant within environments until they identified an opportune time to deploy ransomware.

To gain access to target networks, the recent ransomware campaigns exploited internet-facing systems with the following weaknesses:

- Remote Desktop Protocol (RDP) or Virtual Desktop endpoints without multi-factor authentication (MFA)

- Older platforms that have reached end of support and are no longer getting security updates, such as Windows Server 2003 and Windows Server 2008, exacerbated by the use of weak passwords

- Misconfigured web servers, including IIS, electronic health record (EHR) software, backup servers, or systems management servers

- Citrix Application Delivery Controller (ADC) systems affected by CVE-2019-19781

- Pulse Secure VPN systems affected by CVE-2019-11510

Applying security patches for internet-facing systems is critical in preventing these attacks. It’s also important to note that, although Microsoft security researchers have not observed the recent attacks exploiting the following vulnerabilities, historical signals indicate that these campaigns may eventually exploit them to gain access, so they are worth reviewing: CVE-2019-0604, CVE-2020-0688, CVE-2020-10189.

Like many breaches, attackers employed credential theft, lateral movement capabilities using common tools, including Mimikatz and Cobalt Strike, network reconnaissance, and data exfiltration. In these specific campaigns, the operators gained access to highly privileged administrator credentials and were ready to take potentially more destructive action if disturbed. On networks where attackers deployed ransomware, they deliberately maintained their presence on some endpoints, intending to reinitiate malicious activity after ransom is paid or systems are rebuilt. In addition, while only a few of these groups gained notoriety for selling data, almost all of them were observed viewing and exfiltrating data during these attacks, even if they have not advertised or sold yet.

As with all human-operated ransomware campaigns, these recent attacks spread throughout an environment affecting email identities, endpoints, inboxes, applications, and more. Because it can be challenging even for experts to ensure complete removal of attackers from a fully compromised network, it’s critical that vulnerable internet-facing systems are proactively patched and mitigations put in place to reduce the risk from these kinds of attacks.

A motley crew of ransomware payloads

While individual campaigns and ransomware families exhibited distinct attributes as described in the sections below, these human-operated ransomware campaigns tended to be variations on a common attack pattern. They unfolded in similar ways and employed generally the same attack techniques. Ultimately, the specific ransomware payload at the end of each attack chain was almost solely a stylistic choice made by the attackers.

RobbinHood ransomware

RobbinHood ransomware operators gained some attention for exploiting vulnerable drivers late in their attack chain to turn off security software. However, like many other human-operated ransomware campaigns, they typically start with an RDP brute-force attack against an exposed asset. They eventually obtain privileged credentials, mostly local administrator accounts with shared or common passwords, and service accounts with domain admin privileges. RobbinHood operators, like Ryuk and other well-publicized ransomware groups, leave behind new local and Active Directory user accounts, so they can regain access after their malware and tools have been removed.

Vatet loader

Attackers often shift infrastructure, techniques, and tools to avoid notoriety that might attract law enforcement or security researchers. They often retain them while waiting for security organizations to start considering associated artifacts inactive, so they face less scrutiny. Vatet, a custom loader for the Cobalt Strike framework that has been seen in ransomware campaigns as early as November 2018, is one of the tools that has resurfaced in the recent campaigns.

The group behind this tool appears to be particularly intent on targeting hospitals, as well as aid organizations, insulin providers, medical device manufacturers, and other critical verticals. They are one of the most prolific ransomware operators during this time and have caused dozens of cases.

Using Vatet and Cobalt Strike, the group has delivered various ransomware payloads. More recently, they have been deploying in-memory ransomware that utilizes Alternate Data Streams (ADS) and displays simplistic ransom notes copied from older ransomware families. To access target networks, they exploit CVE-2019-19781, brute force RDP endpoints, and send email containing .lnk files that launch malicious PowerShell commands. Once inside a network, they steal credentials, including those stored in the Credential Manager vault, and move laterally until they gain domain admin privileges. The group has been observed exfiltrating data prior to deploying ransomware.

NetWalker ransomware

NetWalker campaign operators gained notoriety for targeting hospitals and healthcare providers with emails claiming to provide information about COVID-19. These emails also delivered NetWalker ransomware directly as a .vbs attachment, a technique that has gained media attention. However, the campaign operators also compromised networks using misconfigured IIS-based applications to launch Mimikatz and steal credentials, which they then used to launch PsExec, and eventually deploying the same NetWalker ransomware.

PonyFinal ransomware

This Java-based ransomware had been considered a novelty, but the campaigns deploying PonyFinal weren’t unusual. Campaign operators compromised internet-facing web systems and obtained privileged credentials. To establish persistence, they used PowerShell commands to launch the system tool mshta.exe and set up a reverse shell based on a common PowerShell attack framework. They also used legitimate tools, such as Splashtop, to maintain remote desktop connections.

Maze ransomware

One of the first ransomware campaigns to make headlines for selling stolen data, Maze continues to target technology providers and public services. Maze has a history of going after managed service providers (MSPs) to gain access to the data and networks of MSP customers.

Maze has been delivered via email, but campaign operators have also deployed Maze to networks after gaining access using common vectors, such as RDP brute force. Once inside a network, they perform credential theft, move laterally to access resources and exfiltrate data, and then deploy ransomware.

In a recent campaign, Microsoft security researchers tracked Maze operators establishing access through an internet-facing system by performing RDP brute force against the local administrator account. Using the brute-forced password, campaign operators were able to move laterally because built-in administrator accounts on other endpoints used the same passwords.

After gaining control over a domain admin account through credential theft, campaign operators used Cobalt Strike, PsExec, and a plethora of other tools to deploy various payloads and access data. They established fileless persistence using scheduled tasks and services that launched PowerShell-based remote shells. They also turned on Windows Remote Management for persistent control using stolen domain admin privileges. To weaken security controls in preparation for ransomware deployment, they manipulated various settings through Group Policy.

REvil ransomware

Possibly the first ransomware group to take advantage of the network device vulnerabilities in Pulse VPN to steal credentials to access networks, REvil (also called Sodinokibi) gained notoriety for accessing MSPs and accessing the networks and documents of customers – and selling access to both. They kept up this activity during the COVID-19 crisis, targeting MSPs and other targets like local governments. REvil attacks are differentiated in their uptake of new vulnerabilities, but their techniques overlap with many other groups, relying on credential theft tools like Mimikatz once in the network and performing lateral movement and reconnaissance with tools like PsExec.

Other ransomware families

Other ransomware families used in human-operated campaigns during this period include:

- Paradise, which used to be distributed directly via email but is now used in human-operated ransomware attacks

- RagnarLocker, which is deployed by a group that heavily uses RDP and Cobalt Strike with stolen credentials

- MedusaLocker, which is possibly deployed via existing Trickbot infections

- LockBit, which is distributed by operators that use the publicly available penetration testing tool CrackMapExec to move laterally

We highly recommend that organizations immediately check if they have any alerts related to these ransomware attacks and prioritize investigation and remediation. Malicious behaviors relevant to these attacks that defenders should pay attention to include:

- Malicious PowerShell, Cobalt Strike, and other penetration-testing tools that can allow attacks to blend in as benign red team activities

- Credential theft activities, such as suspicious access to Local Security Authority Subsystem Service (LSASS) or suspicious registry modifications, which can indicate new attacker payloads and tools for stealing credentials

- Any tampering with a security event log, forensic artifact such as the USNJournal, or a security agent, which attackers do to evade detections and to erase chances of recovering data

Customers using Microsoft Defender Advanced Threat Protection (ATP) can consult a companion threat analytics report for more details on relevant alerts, as well as advanced hunting queries. Customers subscribed to the Microsoft Threat Experts service can also refer to the targeted attack notification, which has detailed timelines of attacks, recommended mitigation steps for disrupting attacks, and remediation advice.

If your network is affected, perform the following scoping and investigation activities immediately to understand the impact of this breach. Using indicators of compromise (IOCs) alone to determine impact from these threats is not a durable solution, as most of these ransomware campaigns employ “one-time use” infrastructure for campaigns, and often change their tools and systems once they determine the detection capabilities of their targets. Detections and mitigations should concentrate on holistic behavioral based hunting where possible, and hardening infrastructure weaknesses favored by these attackers as soon as possible.

Investigate affected endpoints and credentials

Investigate endpoints affected by these attacks and identify all the credentials present on those endpoints. Assume that these credentials were available to attackers and that all associated accounts are compromised. Note that attackers can not only dump credentials for accounts that have logged on to interactive or RDP sessions, but can also dump cached credentials and passwords for service accounts and scheduled tasks that are stored in the LSA Secrets section of the registry.

- For endpoints onboarded to Microsoft Defender ATP, use advanced hunting to identify accounts that have logged on to affected endpoints. The threat analytics report contains a hunting query for this purpose.

- Otherwise, check the Windows Event Log for post-compromise logons—those that occur after or during the earliest suspected breach activity—with event ID 4624 and logon type 2 or 10. For any other timeframe, check for logon type 4 or 5.

Isolate compromised endpoints

Isolate endpoints that have command-and-control beacons or have been lateral movement targets. Locate these endpoints using advanced hunting queries or other methods of directly searching for related IOCs. Isolate machines using Microsoft Defender ATP, or use other data sources, such as NetFlow, and search through your SIEM or other centralized event management solutions. Look for lateral movement from known affected endpoints.

Address internet-facing weaknesses

Identify perimeter systems that attackers might have utilized to access your network. You can use a public scanning interface, such as shodan.io, to augment your own data. Systems that should be considered of interest to attackers include:

- RDP or Virtual Desktop endpoints without MFA

- Citrix ADC systems affected by CVE-2019-19781

- Pulse Secure VPN systems affected by CVE-2019-11510

- Microsoft SharePoint servers affected by CVE-2019-0604

- Microsoft Exchange servers affected by CVE-2020-0688

- Zoho ManageEngine systems affected by CVE-2020-10189

To further reduce organizational exposure, Microsoft Defender ATP customers can use the Threat and Vulnerability Management (TVM) capability to discover, prioritize, and remediate vulnerabilities and misconfigurations. TVM allows security administrators and IT administrators to collaborate seamlessly to remediate issues.

Inspect and rebuild devices with related malware infections

Many ransomware operators enter target networks through existing infections of malware like Emotet and Trickbot. These malware families, traditionally considered to be banking trojans, have been used to deliver all kinds of payloads, including persistent implants. Investigate and remediate any known infections and consider them possible vectors for sophisticated human adversaries. Ensure that you check for exposed credentials, additional payloads, and lateral movement prior to rebuilding affected endpoints or resetting passwords.

Building security hygiene to defend networks against human-operated ransomware

As ransomware operators continue to compromise new targets, defenders should proactively assess risk using all available tools. You should continue to enforce proven preventive solutions—credential hygiene, minimal privileges, and host firewalls—to stymie these attacks, which have been consistently observed taking advantage of security hygiene issues and over-privileged credentials.

Apply these measures to make your network more resilient against new breaches, reactivation of dormant implants, or lateral movement:

- Randomize local administrator passwords using a tool such as LAPS.

- Apply Account Lockout Policy.

- Ensure good perimeter security by patching exposed systems. Apply mitigating factors, such as MFA or vendor-supplied mitigation guidance, for vulnerabilities.

- Utilize host firewalls to limit lateral movement. Preventing endpoints from communicating on TCP port 445 for SMB will have limited negative impact on most networks, but can significantly disrupt adversary activities.

- Turn on cloud-delivered protection for Microsoft Defender Antivirus or the equivalent for your antivirus product to cover rapidly evolving attacker tools and techniques. Cloud-based machine learning protections block a huge majority of new and unknown variants.

- Follow standard guidance in the security baselines for Office and Office 365 and the Windows security baselines. Use Microsoft Secure Score assesses to measures security posture and get recommended improvement actions, guidance, and control.

- Turn on tamper protection features to prevent attackers from stopping security services.

- Turn on attack surface reduction rules, including rules that can block ransomware activity:

- Use advanced protection against ransomware

- Block process creations originating from PsExec and WMI commands

- Block credential stealing from the Windows local security authority subsystem (lsass.exe)

For additional guidance on improving defenses against human-operated ransomware and building better security posture against cyberattacks in general, read Human-operated ransomware attacks: A preventable disaster.

Microsoft Threat Protection: Coordinated defense against complex and wide-reaching human-operated ransomware

What we’ve learned from the increase in ransomware deployments in April is that attackers pay no attention to the real-world consequences of disruption in services—in this time of global crisis—that their attacks cause.

Human-operated ransomware attacks represent a different level of threat because adversaries are adept at systems administration and security misconfigurations and can therefore adapt to any path of least resistance they find in a compromised network. If they run into a wall, they try to break through. And if they can’t break through a wall, they’ve shown that they can skillfully find other ways to move forward with their attack. As a result, human-operated ransomware attacks are complex and wide-reaching. No two attacks are exactly the same.

Microsoft Threat Protections (MTP) provides coordinated defenses that uncover the complete attack chain and help block sophisticated attacks like human-operated ransomware. MTP combines the capabilities of multiple Microsoft 365 security services to orchestrate protection, prevention, detection, and response across endpoints, email, identities, and apps.

Through built-in intelligence, automation, and integration, MTP can block attacks, eliminate their persistence, and auto-heal affected assets. It correlates signals and consolidates alerts to help defenders prioritize incidents for investigation and response. MTP also provides a unique cross-domain hunting capability that can further help defenders identify attack sprawl and get org-specific insights for hardening defenses.

Microsoft Threat Protection is also part of a chip-to-cloud security approach that combines threat defense on the silicon, operating system, and cloud. Hardware-backed security features on Windows 10 like address space layout randomization (ASLR), Control Flow Guard (CFG), and others harden the platform against many advanced threats, including ones that take advantage of vulnerable kernel drivers. These platform security features seamlessly integrate with Microsoft Defender ATP, providing end-to-end security that starts from a strong hardware root of trust. On Secured-core PCs these mitigations are enabled by default.

We continue to work with our customers, partners, and the research community to track human-operated ransomware and other sophisticated attacks. For dire cases customers can use available services like the Microsoft Detection and Response (DART) team to help investigate and remediate.

Microsoft Threat Protection Intelligence Team

Appendix: MITRE ATT&CK techniques observed

Human-operated ransomware campaigns employ a broad range of techniques made possible by attacker control over privileged domain accounts. The techniques listed here are techniques commonly used during attacks against healthcare and critical services in April 2020.

Credential access

Persistence

Command and control

Discovery

Execution

Lateral movement

Defense evasion

- T1070 Indicator Removal on Host | Clearing of event logs using wevutil, removal of USNJournal using fsutil, and deletion of slack space on drive using cipher.exe

- T1089 Disabling Security Tools | Stopping or tampering with antivirus and other security using ProcessHacker and exploitation of vulnerable software drivers

Impact

READ MORE HERE