Stories Of Dealing With Ransomware Gangs

Hacking. Disinformation. Surveillance. CYBER is Motherboard’s podcast and reporting on the dark underbelly of the internet.

Kat Garcia is a cybersecurity researcher at Emsisoft, where, as part of her work, she tracks a ransomware gang called Cl0p.

Yet, she was surprised when she got an email at the end of last month from the hackers. In the message, the Cl0p hackers told her they had broken into the servers of a clothing shop for expecting mothers and they had her phone, email, home address, credit card information, and Social Security number.

“We inform you that information about you and your purchases, as well as your payment details, will be published on the darknet if the company does not contact us,” the hackers wrote. “Call or write to this store and ask to protect your privacy.”

Garcia said that this incident “shows how far threat actors are willing to go to monetize their crimes.”

The C10p cybercriminals are now trying to recruit customers of the breached companies to help them exhort the companies they hacked. It’s the latest twist in the hacking group’s attempts to extort money from victims, and it’s one of the reasons that Cl0p has become one of the most interesting—and fearsome—hacking groups of early 2021.

“This is the first time I can recall a ransomware group using contact information of customers to reach out en masse through email,” Brett Callow, a security researcher at Emsisoft, which specializes in tracking ransomware, said in a phone call.

“In our team there is no me, there is only us, as a rule, most people are interchangeable.”

Security researchers who have tracked Cl0p describe the group in blog posts and to Motherboard as a “criminal enterprise” that is “ruthless,” “sophisticated and innovative,” “well-organized and well-structured,” and “very active—almost tireless.”

The group’s recent victims include: oil giant Shell, security company Qualys, U.S. bank Flagstar, the controversial global law firm Jones Day, Stanford University, and University of California, among several others, all victims of a supply chain hack against Accellion, a company that provides a file transfer application.

Cl0p, also known as TA505 and FIN11, has been around for at least three years, according to several security firms that have been tracking the group. But the hackers have recently grabbed more headlines and become more prominent after gaining access to a treasure trove of sensitive data from dozens of companies—and all thanks to one single hack.

The hackers are the benefactors—and, some think, the culprit—of the supply chain attack against the Accellion File Transfer Appliance (FTA), a file-sharing service used by around 300 companies all over the world, according to Accellion. Security researchers still don’t know for sure whether Cl0p was the hacking group that compromised Accellion, or if they are just the ones that are monetizing the stolen data after the original hacking group gave them access.

In an email conversation, Motherboard asked the hackers whether they were behind the Accellion supply chain hack, and how they did it.

“Yes. Somehow,” the hackers responded.

Do you have knowledge of the inner workings of Cl0p or another ransomware gang? We’d love to hear from you. Using a non-work phone or computer, you can contact Lorenzo Franceschi-Bicchierai securely on Signal at +1 917 257 1382, lorenzofb on Wickr, OTR chat at lorenzofb@jabber.ccc.de, or email lorenzofb@vice.com

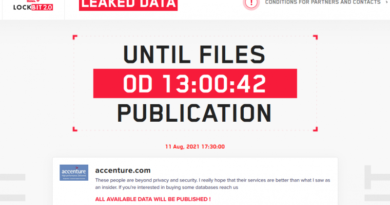

Cl0p published the name of the companies, and a sample of the stolen data, on its website, CL0P^_- LEAKS. As researchers from Talon, a division of South Korean cybersecurity company S2WLAB said in an email, “some companies are found to be removed on the data leakage page on the dark web,” presumably because they paid the ransom.

There are 52 companies on CL0P^_- LEAKS as of last week. These are presumably companies that have not paid the ransom requested by the hackers. Antonis Terefos, a researcher at Fox-IT who has studied the group, estimated that the group has hacked more than 150 companies.

As part of these breaches, Cl0p has posted victims’ names, social security numbers, home addresses, financial documents, passport information, and other sensitive data on their website, where they publicize their hacks in an attempt to show what data they have in their hands, and what they are capable of if the victim’s don’t pay up.

An Accellion spokesperson downplayed the extent of the hack, saying in an email that “out of approximately 300 total FTA clients, fewer than 100 were victims of the attack. Within this group, fewer than 25 appear to have suffered significant data theft.”

Cl0p normally contacts the breached companies directly via email, offering to negotiate a payment to avoid the leak of the stolen data on their chat portal. If the company agrees and pays quickly, the hackers don’t leak any data, nor put the company’s name on their website. Sometimes they even show a video as proof they deleted the sensitive data after a payment. If the company refuses to engage, the hackers start leaking some data, according to multiple security researchers who are tracking Cl0p.

“In the communications that they’ve had with victims that we’ve seen, they are relatively professional and respectful. So they do offer discounts,” Kimberly Goody, the manager of the financial crime analysis team at FireEye, told Motherboard in a phone call.

It seems that Cl0p knows that as long as they get a few big victims they can make good money.

In one case observed by FireEye at the end of 2020, the Cl0p hackers asked the victim for $20 million. After some negotiations, the victim company was able to get the price down to $6 million. South Korean security firm S2WLAB said in January they saw a victim pay 220 bitcoin, which appears to be the same case FireEye observed.

In another case, the hackers offered another victim a discount based on how quickly they could reach an agreement: 30 percent discount if within three or four days, 20 percent if within 10 days, and 10 percent if it’s within 20 days, according to Goody.

The hackers, however, have made some mistakes. To communicate with victims, Cl0p sometimes uses a custom chat portal that is not protected by a password. That makes the negotiations visible to researchers and anyone who can guess the URL, according to Goody, who said that that is how FireEye was able to observe some conversations between the group and its victims.

Unlike other ransomware groups such as Netwalker, REvil, and CONTI, Cl0p doesn’t run an affiliate program, meaning they don’t share their malware with other cybercriminals to get a share of their proceedings. Cl0p appears to run the whole hacking operation from start to finish, which reduces the size of their earnings, according to Goody.

“They’re content with the slow and steady pace. I mean, it’s not like they aren’t able to make a lot of money potentially, from these compromises, given that they are demanding millions of dollars when they are successful,” Goody said. “They’re not necessarily greedy, like maybe some of these other actors are.”

“It is indecent to ask strangers about how much they earn,” the hackers said.

The hackers also declined to say much about themselves.

“In our team there is no me, there is only us, as a rule, most people are interchangeable.” they wrote in the email interview. “There are several people in the team and we have existed for several years.”

While the hackers’ identities are unknown, security researchers agree that the group is likely based in a country part of the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS), which is formed by Russia and former Soviet Union countries.

“It’s only a matter of time before they make a mistake which will help [law enforcement to identify its members.”

Goody said that Cl0p’s ransomware has metadata in Russian language, and the hackers appear to stop their activities during Russian holidays. Moreover, she added, their malware is programmed to check if the infected computers use the Russian language character set, or keyboard layouts for countries in the CIS. If that’s the case, the ransomware deletes itself.

This is a true and tested strategy to avoid attracting the attention of authorities in Russia or other Eastern European countries, which are sometimes believed to tolerate cybercrime as long as it doesn’t impact their own citizens. Despite these precautions, some believe Cl0p is getting a bit too popular for its own good.

“They are getting too much attention, not a good thing. Last year, nobody was interested in them. Now, there are many reports writing about them and [law enforcement] cases ongoing,” a security researcher, who asked to remain anonymous because he was not authorized to speak to the press, told Motherboard in an email. “Maybe they’ll rebrand like other ransomware gangs did to get out of the focus. Maybe they continue to operate because they reside in a safe haven like a [Commonwealth of Independent States] country. Hopefully, their doors get kicked in one morning…”

Terefos agreed.

“It’s only a matter of time before they make a mistake which will help [law enforcement to identify its members,” he said.

Subscribe to our cybersecurity podcast, CYBER.

READ MORE HERE