The SIM Hijackers

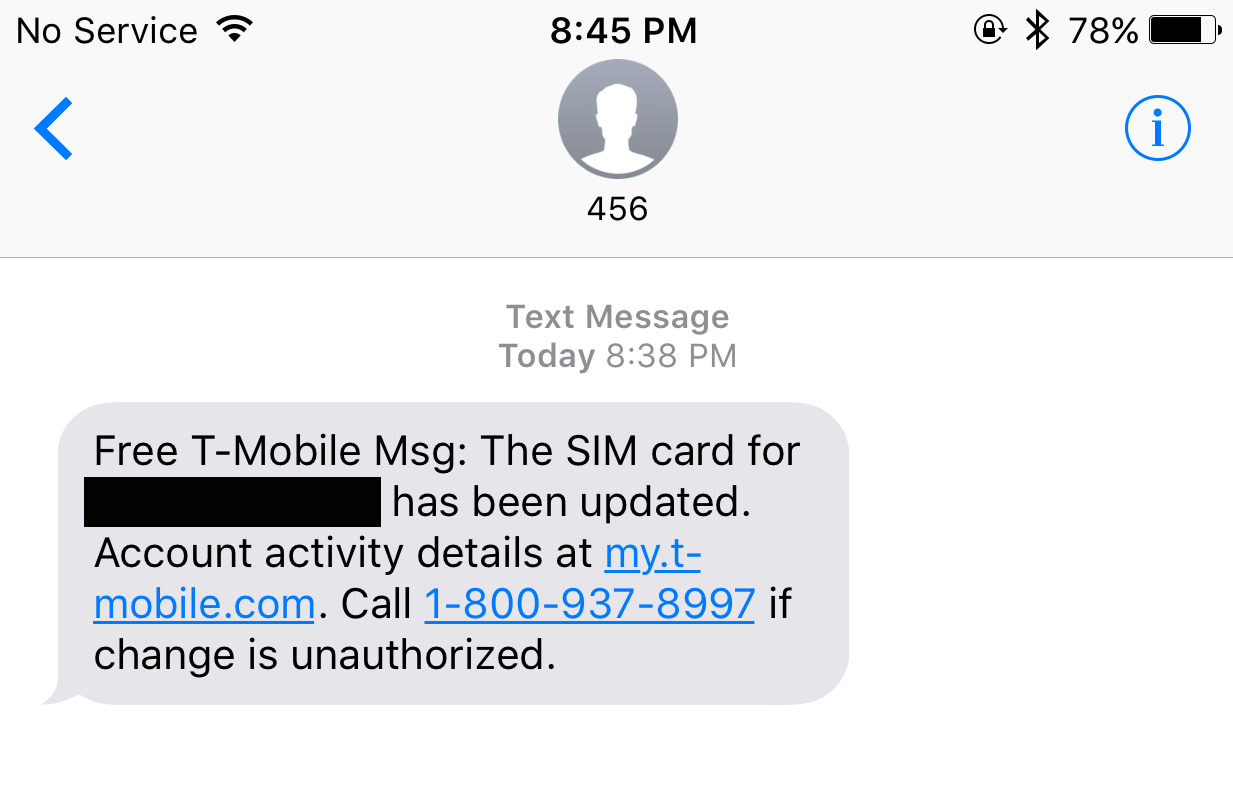

It seemed like any other warm September night in the suburbs of Salt Lake City. Rachel Ostlund had just put her kids to bed and was getting ready to go to sleep herself. She was texting with her sister when, unexpectedly, her cell phone lost service. The last message Rachel received was from T-Mobile, her carrier. The SIM card for her phone number, the message read, had been “updated.”

Rachel did what most people would have done in that situation: she turned the phone off and on again. It didn’t help.

She walked upstairs and told her husband Adam that her phone wasn’t working. Adam tried to call Rachel’s number using his cell phone. It rang, but the phone in Rachel’s hands didn’t light up. Nobody answered. Rachel, meanwhile, logged into her email and noticed someone was resetting the passwords on many of her accounts. An hour later, Adam got a call.

“Put Rachel on the phone,” demanded a voice on the other end of the line. “Right now.”

Adam said no, and asked what was going on.

“We’re fucking you, we’re raping you, and we’re in the process of destroying your life,” the caller said. “If you know what’s good for you, put your wife on the phone.”

Adam refused.

“We’re going to destroy your credit,” the person continued, naming some of Rachel and Adam’s relatives and their addresses, which the couple thinks the caller obtained from Rachel’s Amazon account. “What would happen if we hurt them? What would happen if we destroyed their credit and then we left them a message saying it was because of you?”

“We’re fucking you, we’re raping you, and we’re in the process of destroying your life.”

The couple didn’t know it yet, but they had just become the latest victims of hackers who hijack phone numbers in order to steal valuable Instagram usernames and sell them for Bitcoin. That late summer night in 2017, the Ostlunds were talking to a pair of these hackers who’d commandeered Rachel’s Instagram, which had the handle @Rainbow. They were now asking Rachel and Adam to give up her @Rainbow Twitter account.

In the buzzing underground market for stolen social media and gaming handles, a short, unique username can go for between $500 and $5,000, according to people involved in the trade and a review of listings on a popular marketplace. Several hackers involved in the market claimed that the Instagram account @t, for example, recently sold for around $40,000 worth of Bitcoin.

Has your phone or Instagram been hacked? Tell us your story. You can contact this reporter securely on Signal at +1 917 257 1382, OTR chat at lorenzo@jabber.ccc.de, or email lorenzo@motherboard.tv

By hijacking Rachel’s phone number, the hackers were able to seize not only Rachel’s Instagram, but her Amazon, Ebay, Paypal, Netflix, and Hulu accounts too. None of the security measures Rachel took to secure some of those accounts, including two-factor authentication, mattered once the hackers took control of her phone number.

“That was a very tense night,” Adam remembered. “I can’t believe they had the gall to call us.”

Image: Shutterstock

AN OVERLOOKED THREAT

In February, T-Mobile sent a mass text warning customers of an “industry-wide” threat. Criminals, the company said, are increasingly utilizing a technique called “port out scam” to target and steal people’s phone numbers. The scam, also known as SIM swapping or SIM hijacking, is simple but tremendously effective.

First, criminals call a cell phone carrier’s tech support number pretending to be their target. They explain to the company’s employee that they “lost” their SIM card, requesting their phone number be transferred, or ported, to a new SIM card that the hackers themselves already own. With a bit of social engineering—perhaps by providing the victim’s Social Security Number or home address (which is often available from one of the many data breaches that have happened in the last few years)—the criminals convince the employee that they really are who they claim to be, at which point the employee ports the phone number to the new SIM card.

Game over.

“With someone’s phone number,” a hacker who does SIM swapping told me, “you can get into every account they own within minutes and they can’t do anything about it.”

A screenshot of the text message Rachel Ostlund received when hackers took over her phone number.

From there, the victim loses service, given only one SIM card can be connected to the cell phone network with any given number at a time. And the hackers can reset the victim’s accounts and can often bypass security measures like two-factor authentication by using the phone number as a recovery method.

Certain services, including Instagram, require that users provide a phone number when setting up two-factor, a stipulation with the unintended effect of giving hackers another method of getting into an account. That’s because if hackers take over a target’s number, they can skirt two-factor and seize their Instagram account without even knowing the account’s password. (Read our guide on how to protect your phone number, and the accounts linked to it, from hackers.)

Eric Taylor, a hacker formerly known as CosmoTheGod, used this technique for some of his most famous exploits, like the time he hacked into the email account of CloudFlare’s CEO in 2012. Taylor, who now works at security firm Path Network, told me that having a phone number linked to any of your online accounts makes you “vulnerable to basically 13- to 16-year-old kids taking over your accounts just by taking over your phone within five minutes of calling your fucking provider.”

“It happens all the time,” he added.

Got a tip? You can contact this reporter securely on Signal at +1 917 257 1382, OTR chat at lorenzo@jabber.ccc.de, or email lorenzo@motherboard.tv

Roel Schouwenberg, the director of intelligence and research at Celsus Advisory Group, has done research on issues like SIM swapping, bypassing two-factor authentication, and abusing account recovery mechanisms. In his opinion, no phone number is completely safe, and consumers need to realize that.

“Any type of number can be ported,” Schouwenberg told me. “A determined and resourced criminal actor will be able to get at least temporary access to a number, which is often enough to successfully complete a heist.”

That’s troubling because cell phone numbers have become “master keys” to our whole online identity, as he argued in a blog post last year.

“Most systems aren’t designed to deal with attackers taking over phone numbers. This is very, very bad,” Schouwenberg wrote. “Our phone number has become an almost irrevocable credential. It was never intended as such, just like Social Security Numbers were never meant as credentials. A phone number provides the key to the kingdom for most services and accounts today.”

What hackers do once they have control of your phone number depends on precisely what they’re after.

‘I TAKE THEIR MONEY AND LIVE MY LIFE’

If your bike gets stolen, you should check Craigslist to see if someone is selling it on the black market. If your Instagram account gets stolen via a SIM swap, you should check OGUSERS.

At first glance, OGUSERS looks like any other forum. There’s a “spam/joke” section and another for chatting on topics like music, entertainment, anime, and gaming. But the largest and most active section is the marketplace where users buy and sell social media and gaming handles—sometimes for thousands of dollars.

In a recent post, someone sold the Instagram account @Bitcoin for $20,000, according to one of the forum’s administrators. In a listing that was still online as of June 13, a user was advertising the sale of @eternity on Instagram for $1,000.

These are just two examples of the kind of accounts for sale on OGUSERS. The forum was launched in April 2017 to give people a place to purchase and sell “OG” usernames. (The forum takes its name from the slang term OG, short for “original gangster.”) An OG on social media is any username that is considered cool, perhaps because it’s a unique word like @Sex, @Eternity, or @Rainbow. Or perhaps because it’s a very short handle, such as @t or @ty. Celebrities have also been targeted.

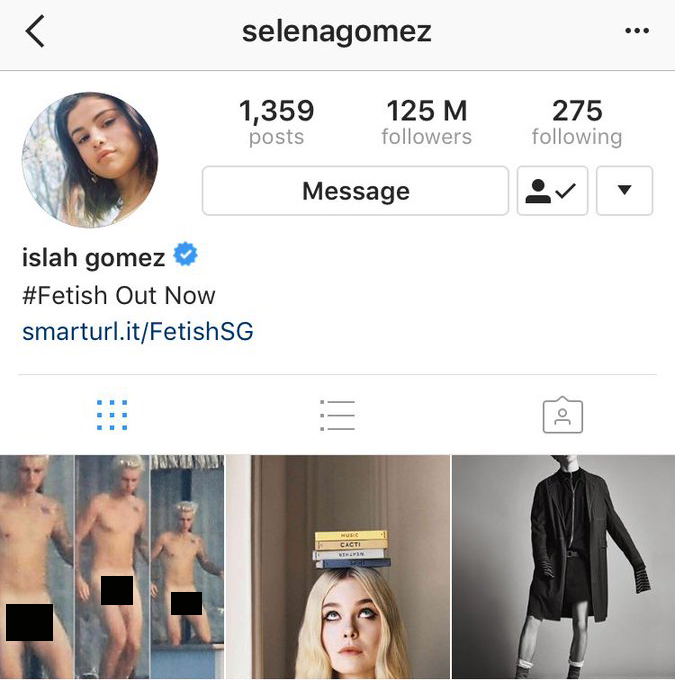

A screenshot of Selena Gomez’s Instagram account after it was hacked.

In August of last year, for example, hackers hijacked the Instagram account of Selena Gomez and posted nude photos of Justin Bieber. The first name on Gomez’s account name was also changed to “Islah”, identical to that used at the time by someone on OGUSERS who went by the username Islah. According to hackers in OGUSERS, the people claiming to be behind the Gomez hack said they did so by taking over the cell phone number associated with the singer-actress’s Instagram account, which had 125 million followers when it was seized.

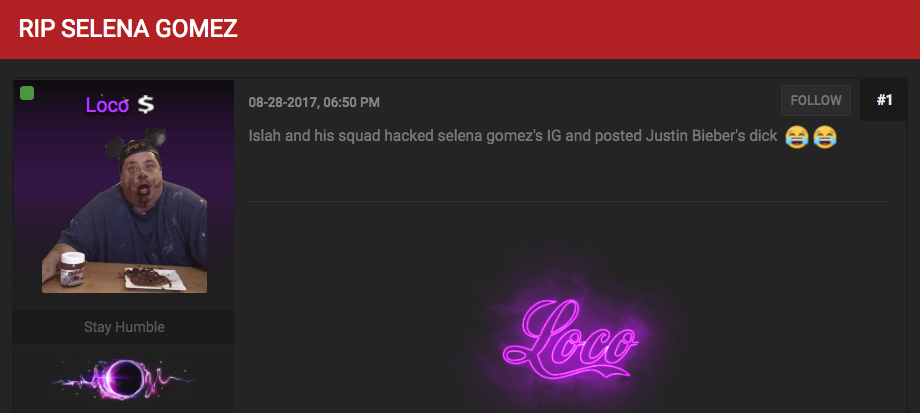

“Damn they legit hacked the most followed person on Instagram,” an OGUSERS member commented in a thread titled “RIP SELENA GOMEZ.”

A spokesperson for Gomez declined to comment via email.

A post in the OGUSERS forum thread where members commented on the Selena Gomez hack.

As of June of this year, OGUSERS had more than 55,000 registered users and 3.2 million posts. About 1,000 active users log in each day.

Users on the site are not allowed to discuss SIM swapping. When someone alludes to the increasingly popular tactic, others often post messages to the effect of, “I don’t condone any illegal activities.” Yet, two longtime members, who go by Ace (who is listed as one of the moderators of the forum) and Thug, told me that SIM swapping is a common method OGUSERS members use to steal usernames.

In order to steal a username via SIM swapping, one must first know what number is linked to that username.

Finding that kind of information online, it turns out, isn’t as hard as one might think.

Last year, hackers put up a service called Doxagram, where you could pay to find out what phone number and email were behind a given Instagram account. (When it launched, Doxagram was advertised on OGUSERS.) And thanks to a series of high-profile hacks, Social Security Numbers have long been relatively easy to find if you know where to look on the internet’s underground.

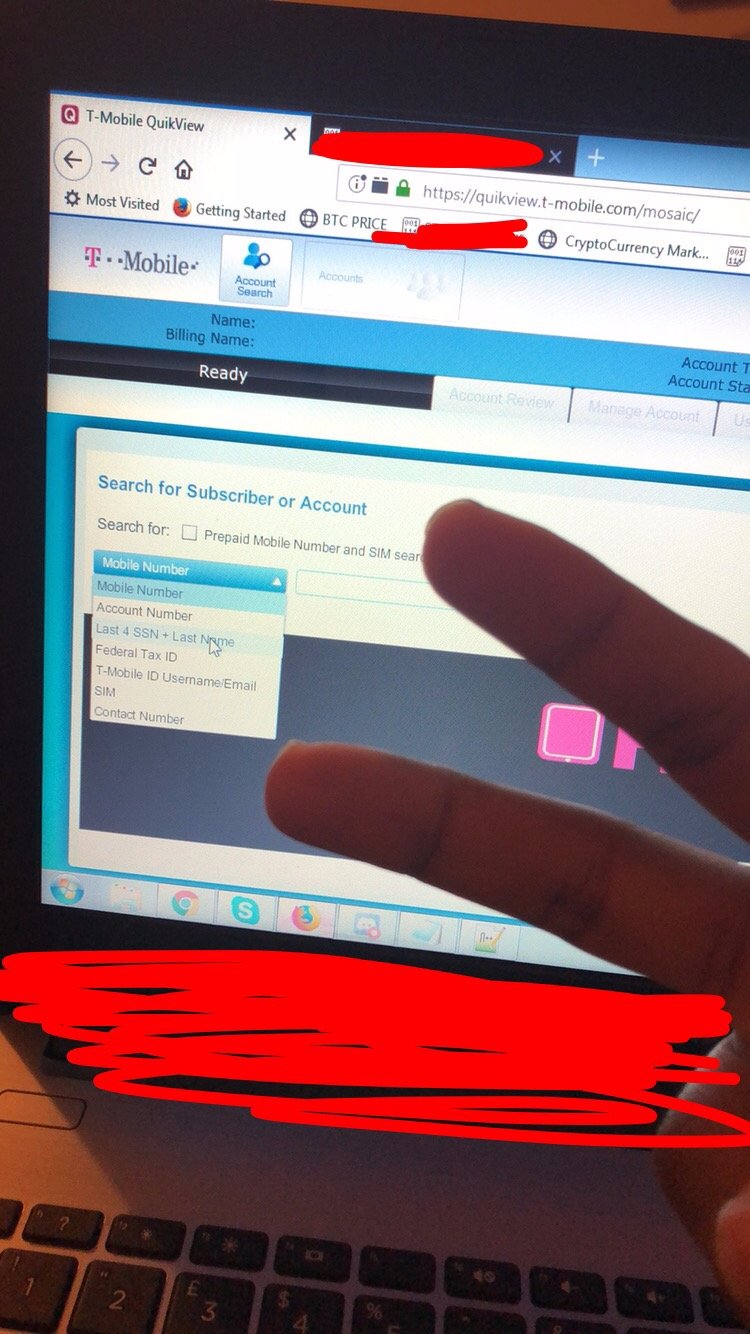

Ace claimed to no longer be in the business of selling usernames. Thug said they do SIM swaps by using an internal T-Mobile tool to look up subscribers’ data. During our chat, the hacker showed me a screenshot of them browsing the tool.

A photo that the hacker Thug sent me during a recent chat.

I gave Thug my phone number as a test, and the hacker sent back a screenshot that contained my home address, IMSI number (a standardized unique number that identifies subscribers), and other theoretically secret account information. Thug even saw the special instructions that I gave T-Mobile to protect my account.

“I’m paranoid,” I said.

“Indeed, it’s a crazy online world,” Thug replied.

In fact, it wasn’t the first time a stranger had accessed private information of mine—supposedly protected by T-Mobile.

Last year, a security researcher was able to exploit a bug in a T-Mobile site to access pretty much the same information. After patching it, T-Mobile initially dismissed the impact of the bug, saying no one had exploited it. But in reality, many people had. A tutorial on YouTube that explained exactly how to take advantage of the bug to access people’s private data had been up for weeks before the company plugged the hole.

Thug said that in the last few years, telecom providers have been making it harder for hackers like them.

“It used to be as simple as calling up a phone company (for example, T-Mobile) and telling them to change the SIM card on the number,” Thug told me in a recent online chat. “Now you need to know people that work there and they’ll give the PIN for literally $100.”

Thug and Ace explained that many hackers now recruit customer support or store employees who work at T-Mobile and other carriers and bribe them $80 or $100 to perform a SIM swap on their target. Thug claimed they got access to the T-Mobile tool by bribing an insider, but Motherboard could not verify this claim. T-Mobile declined to answer questions on whether the company had any evidence of insiders being involved in SIM swap scams.

“Insiders make the job a lot faster and easy,” Thug said.

Finding an insider isn’t the main challenge, Ace added. “It’s convincing them to do what you want that is the hard part.”

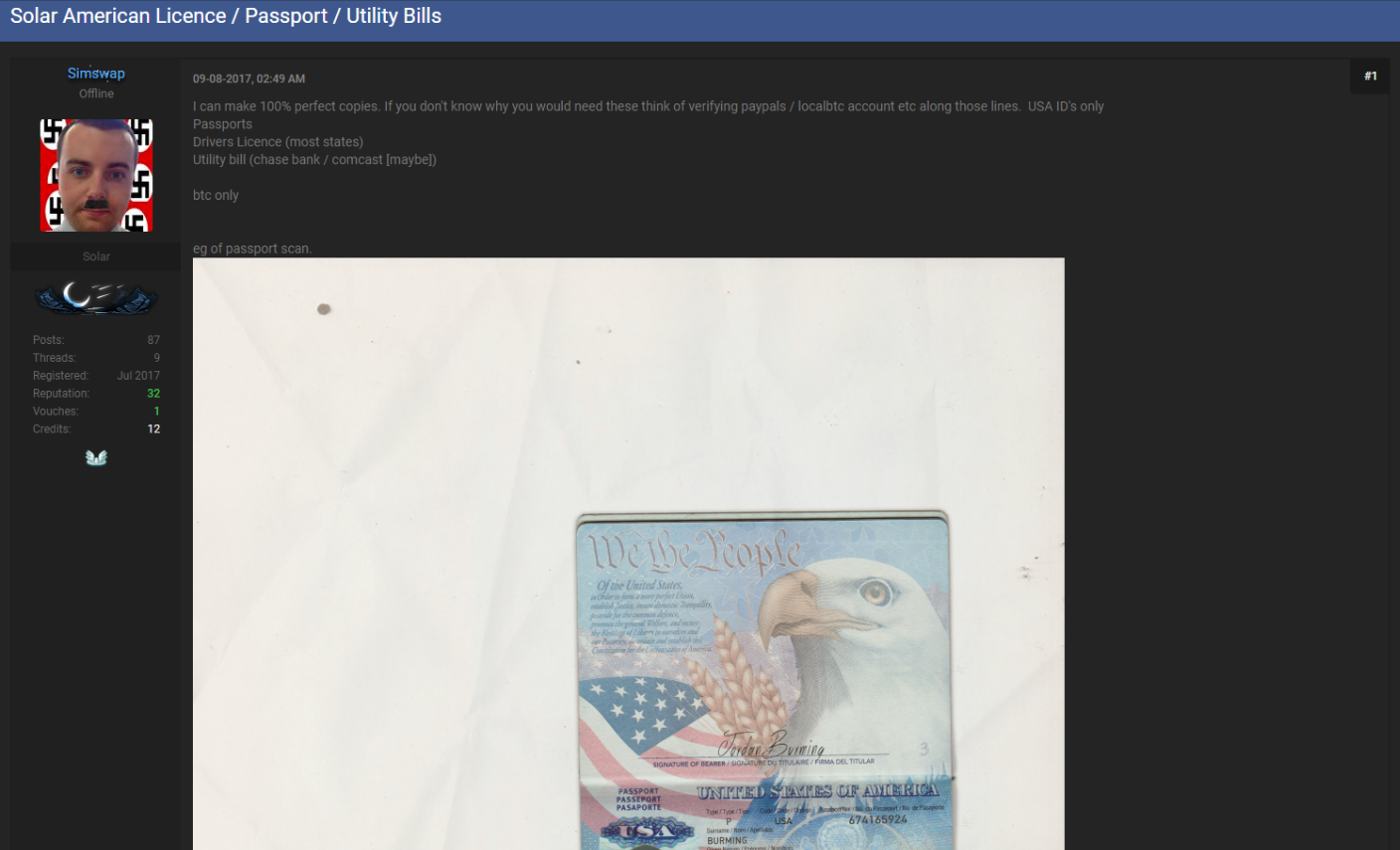

A post on OGUSERS by someone nicknamed “Simswap,” who was advertising a service for fake IDs and other documents.

A recent investigation by security firm Flashpoint found that criminals are increasingly getting help from telecom insiders to perform SIM swaps. Lorrie Cranor, a former FTC chief technologist, said that she has seen evidence of insiders being involved in these attacks multiple times. Taylor, the security researcher and SIM swapping pioneer, said that he knows of people who get help from store employees. Security reporter Brian Krebs recently wrote about a case where a T-Mobile store employee made an unauthorized SIM swap to steal an Instagram account.

SIM swapping isn’t the only way people on OGUSERS take control of accounts, of course. Though not as effective as SIM swapping, a less nefarious hijack known as “turboing” uses a program that automatically tries to claim usernames when they become available, Thug told me.

But if stealing phone numbers is the more effective approach, it’s not for lack of requiring considerable skill. Ace and Thug estimated that only around 50 OGUSERS members have the social engineering and tech tools to be able to do it.

In a video posted to YouTube, an alleged OGUSERS member with forum members’ usernames written on his chest can be seen screaming “I love OGU.”

When I was chatting with them, I asked Thug and Ace if they feel any remorse when it comes to hacking into people’s online accounts, cryptocurrency wallets, or banks.

“Not at all, sad to say,” Ace said. “I take their money and live my life. Their fault for not staying secure.”

What criminal hackers like them do is basically harmless, Thug added, especially for usernames.

“It’s just a username. Nothing special,” Thug said. “Not losing any money, just a dumb username.”

A GROWING PROBLEM

Whether they’re selling Instagram usernames or not, SIM swappers can make serious money.

“The entire schema is super lucrative,” Andrei Barysevich, a security researcher at Recorded Future who has studied the criminal business of SIM swapping, told me. “If you know how to swap a SIM card it’s a venue to make a lot of money.”

Take Cody Brown, the founder of virtual reality company IRL VR, who lost more than $8,000 in Bitcoin in just 15 minutes last year after hackers took over his cell number and then used that to hack into his email and Coinbase account. At the time of Brown’s hack, such attacks were rampant enough that Authy, an app that provides two-factor authentication for some of the most popular online cryptocurrency exchanges, alerted users about SIM swapping and put extra security features to stop hackers.

Or consider the message I received on the encrypted chat app Signal last year, after Motherboard revealed that a T-Mobile website had a bug that allowed hackers to obtain personal customer information, which could then be used to social engineer customer representatives and run a SIM swap.

“Just wanna say fuck you for leaking the [T-Mobile] API exploit you cock munching faggot fuck,” the person, who went by the nickname NoNos, wrote. “It wouldn’t be patched if you didn’t write an article about it for all the world to see and contact TMO telling them about it.”

The person went on to claim that they used the bug to hack several people, and that they were a SIM swapper. They also said they used the technique to target wealthy people they could then rob.

“I’ve made 300k [ sic] in a day before through other methods,” NoNos said, though Motherboard was unable to corroborate this number.

“If ‘people’ with the ability to do this can SIM swap anyone’s number in the country, why would you target usernames and random people when you can target people with lots of money? Like investors or stock traders. Hedge fund managers etc,” NoNos continued.

Besides Selena Gomez, other notable victims of SIM swapping include Black Lives Matter activist Deray McKesson; Dena Haritos Tsamitis, the founder of Carnegie Mellon University’s cybersecurity and privacy institute CyLab; and YouTube star Boogie2988.

In the last few months, more than 30 victims of SIM swapping reached out to me to share horror stories of their online and offline lives being subsequently upended. It’s safe to say this has happened to at least hundreds of people in the US, though it’s hard to nail down exactly how many individuals have been hacked this way. Only cell phone carriers know the extent of the problem, and these telcos, perhaps unsurprisingly, aren’t inclined to talk about it.

Cranor, now a professor at Carnegie Mellon University, said she tried to find out just how prevalent this hack was while serving as chief technologist at the Federal Trade Commission in 2016 (Cranor herself became a victim of SIM swapping that same year; at the time, Cranor told me, she had never even heard of SIM swapping.) But despite the power and influence that came with her role at the FTC, none of the cell phone providers shared any data on how common these attacks are when Cranor requested numbers.

“The carriers are clearly not doing enough,” Cranor told me over the phone. “They tell me that they’re increasing what they’re doing, and that maybe what happened to me wouldn’t have happened today, but I’m not convinced. I have not seen much evidence that they really ramped things up. They really need to treat this as something that is a critical authentication issue.”

Carriers are well aware of SIM swapping, she added. “Although they don’t like to admit it.”

Motherboard reached out to AT&T, Verizon, Sprint, and T-Mobile—the big four US cell phone providers—requesting data on the prevalence of SIM swapping. None of them agreed to provide such information.

An AT&T spokesperson said this kind of fraud “affects a small number of our customers and this is rare for us,” but did not respond when asked to clarify what “small number” means.

“SIM swap/port out fraud has been an industry problem for some time,” a T-Mobile spokesperson said in a statement. The company, she added, is combating these attacks by asking customers to add extra security, such as requiring PINs and passcodes for porting out numbers, and evaluating new methods to verify changes to customer accounts. The rep declined my request to arrange a phone interview with T-Mobile executives and did not answer questions about how prevalent and widespread these attacks are, including how many people have been hit.

“I can’t really understand why that’s relevant,” the spokesperson said. “It’s going to be a small number when you consider we have 72 million customers. But obviously no company wants to see this happen to even one customer.” (In October of last year, T-Mobile alerted “a few hundred customers” who were targeted by hackers.)

Sprint declined to provide any numbers or data on SIM swapping incidents, and instead sent a statement suggesting that their customers regularly change their passwords. A Verizon spokesperson also did not provide any data about the prevalence of SIM hijacking, but said it requires “correct account and password/PIN match” to do SIM swaps.

Earlier this year, these four major carriers announced the Mobile Authentication Taskforce, a joint initiative to create a new solution to allow customers to authenticate to websites and apps using credentials on their phones. The tech press touted this as a potential replacement for SMS-based two-factor authentication, which is widely considered broken. But there aren’t details on how this new solution will actually be implemented, and it’s still unclear if it will help mitigate SIM swapping.

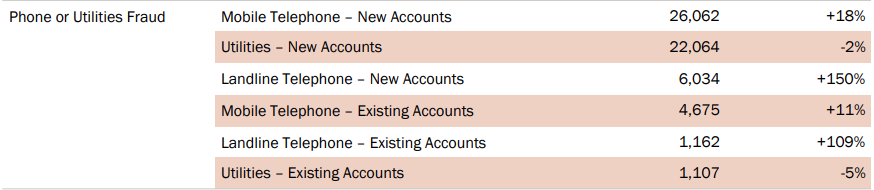

An FTC spokesperson pointed to the agency’s 2017 Consumer Sentinel Data Book, a document that summarized consumer reports of fraud, scams, and identity theft, among others, though it lacked a specific entry for SIM swapping. The spokesperson said such an item “might come under” phone or utilities fraud, which records more than 30,000 reports of mobile telephone fraud.

Screenshot from page 14 of of the FTC’s Consumer Sentinel Data Book

A spokesperson with the Federal Bureau of Investigation, an agency that probes nationwide scams and crimes of the sort, said the bureau has no data on this type of hack.

Even if the numbers are small, these hacks can be damaging and hurtful. At the very least, recovering from one requires a significant amount of time and effort. Just ask Fanis Poulinakis, a SIM swapping victim, who told me about getting SIM swapped earlier this year.

After his phone stopped working all of a sudden one day, Poulinakis said he immediately logged in to his online bank account. “Et voila!” he said. “$2,000 were gone.” Poulinakis spent the entire day between T-Mobile and Chase Bank, trying to piece together what had happened.

“What a nightmare.”

FROM VICTIMS TO SLEUTHS

The night of September 6, 2017, wore on for Rachel and Adam Ostlund.

Adam tried to keep the hackers on the phone as long as he could, mostly to figure out what had happened and what all had been accessed by the criminals, who were growing impatient, demanding the couple give up Rachel’s @Rainbow Twitter account. Having control of both Twitter and Instagram accounts with the same username would have given the hackers a chance to rake in more money in the event of a sale. As other hackers have explained to me, having the original email—or “OGE”—that’s linked to the accounts makes them more valuable, given that it’s harder for the original account holders to recover them from the hackers.

Tired, Adam hung up. The hackers soon texted him.

“Can we just make this quick I need to sleep,” one of them wrote, according to a chat log Adam shared with Motherboard. “Change the email on the Twitter now. Not to be a jerk but if you don’t respond soon, no matter what you got bad things are gonna happen.”

Then the hackers called back. This time, a calmer, less threatening person did the talking.

“It’s not personal,” the second hacker told Adam, apologizing for the tone of the first person, according to a recording of the call. “I can assure you nothing is gonna happen.”

Local law enforcement showed up at the Ostlund’s house during this second call, after Rachel had called the police. When the couple explained what happened, the officers seemed confused and said they couldn’t really help. The couple spent the rest of the night trying to recover from the hack. Once they got the phone number back from T-Mobile, they used it to reset all passwords, just like the hackers did, to recover the seized accounts. Except the @Rainbow Instagram, of which the hackers now had full control.

Three days later, Rachel and Adam took matters into their own hands. They would hunt down the hackers themselves.

Rachel said she noticed that her Instagram account had been essentially reset with a single follower: @Golf, whose bio identified the owner as someone named Austin. In that account, the Ostlunds told me they found a picture they believe to have been taken at a concert in Colorado Springs, and that by looking through @Golf’s followers the couple managed to track down the hacker’s Twitter and Facebook account. This led to what they allege to be the hacker’s real identity.

Motherboard was unable to confirm the identity of the hacker.

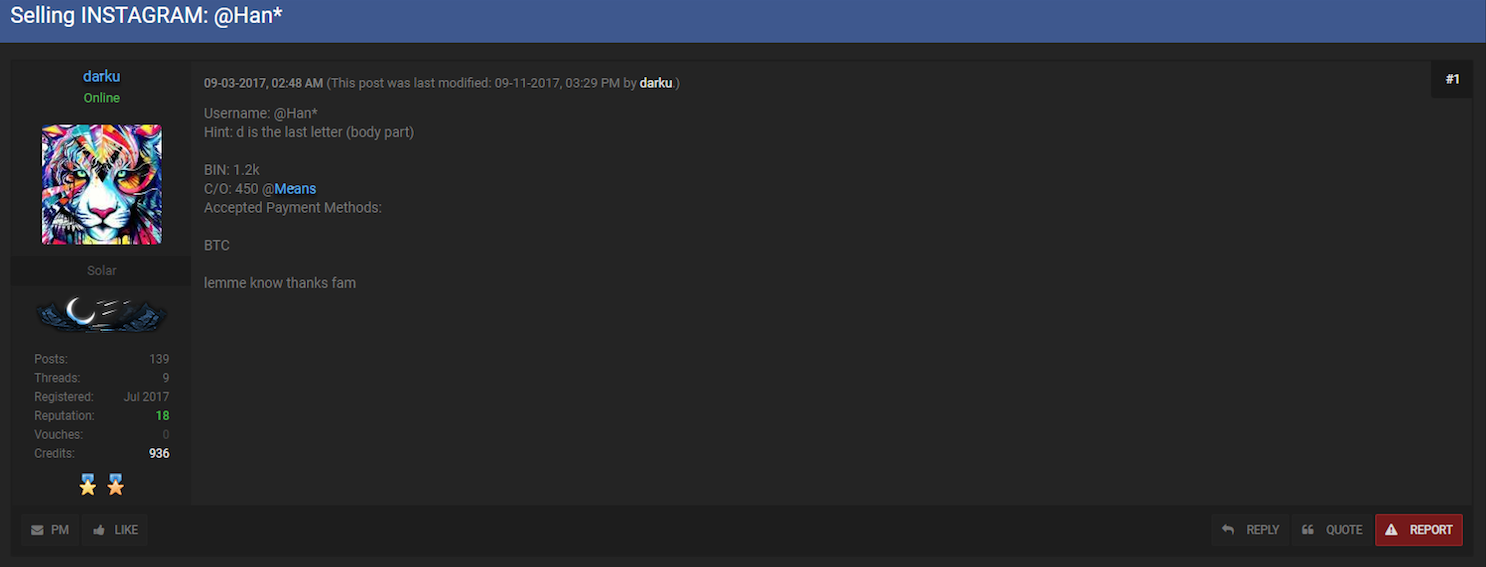

During their investigation, Rachel and Adam also found a post on OGUSERS where a hacker nicknamed Darku was selling @Golf and other unique Instagram usernames. For the couple, this was a telltale that Darku was in control of @Golf and, thus, of @Rainbow.

A post where Darku advertised the sale of the Instagram account @Hand.

In an online chat, Darku told me he is 18 years old and has been part of several hacking groups. He denied doing SIM swapping and to being the hacker who stole @Rainbow and @Hand, claiming he traded the latter from a friend, and that he never owned @Rainbow.

“I don’t subject myself to petty crime,” Darku said. “I have connections everywhere and don’t need to perform fraud to get what I want.”

After I reached out to him on OGUSERS in May, Darku wrote a post warning members that the FBI may be investigating the forum. According to Darku, my questions were suspicious—he wasn’t sure I truly was who I claimed to be.

“Friends of mine have had run ins with the FBI recently regarding some usernames and how they were acquired, personal experience gained,” Darku wrote. “If you’ve been contacted by ANYONE claiming to be from any MAJOR news outlet, please proceed with caution.”

Some users seemed confused, wondering why the bureau would even be interested in a marketplace for usernames.

“It’s not about the usernames,” another user countered. “It’s about the ways that were used to obtain the usernames. I’m positive they know the darker picture of what goes on behind just selling usernames.”

Still other OGUSERS forum members seemed to take it more lightly, joking about getting arrested, or posting memes. My account on the forum was banned, as was the IP address I was using to access it.

An Instagram post by a OGUSERS member, published after Motherboard started reaching out to members of the forum.

Adam shared the information he’d found on Darku with an FBI agent in Salt Lake City who specializes in dark web and cybercrime investigations, according to an email Adam shared with me. Adam also told me that the FBI in Colorado Springs notified him that his report was “accurate” and that investigators are making progress.

Rachel added that the FBI recently informed her and Adam that agents allegedly visited Austin’s house and “scared the heck out of him.” The hacker is “never gonna do this again,” Rachel told me.

In another recent OGUSERS forum thread, Darku wrote that he knows for a fact that the FBI is looking into “whoever extorted the lady” who owned @Rainbow. Darku told me that police have come to talk to him, but “it didn’t have anything to do with me.”

“I do not waste my time harassing other people,” Darku said he told the authorities.

Motherboard was unable to confirm FBI involvement in the case. The bureau typically does not comment on active investigations. A spokesperson from the FBI Salt Lake City office declined to comment. The FBI’s Colorado Springs office could not be reached.

To this day, Instagram has yet to return the @Rainbow account to Rachel. Other victims, such as the owners of the Instagram accounts @Hand and @Joey, all told me they have not gotten their accounts back despite multiple complaints to Instagram.

“We work hard to provide the Instagram community with a safe and secure experience,” an Instagram spokesperson said in a statement. “When we become aware of an account that has been compromised, we shut off access to the account and the people who’ve been affected are put through a remediation process so they can reset their password and take other necessary steps to secure their accounts.”

For traumatized victims, it’s a valuable lesson learned the hard way.

“Our phones are our greatest vulnerability,” Rachel told me.

As Adam put it, the hack taught him that cell phone numbers are the weakest links in our digital lives.

“If someone owns your phone number,” he said, “they own your life.”

Get six of our favorite Motherboard stories every day by signing up for our newsletter.

READ MORE HERE