Threat Actor Names Proliferate, Adding Confusion

The cyberattackers conducting espionage operations on behalf of Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps have been known by a variety of names, depending on the threat intelligence group investigating the attacks: Magic Hound, APT35, Charming Kitten, Cobalt Illusion, TA453, and PHOSPHORUS.

Add one more to the mix: Mint Sandstorm.

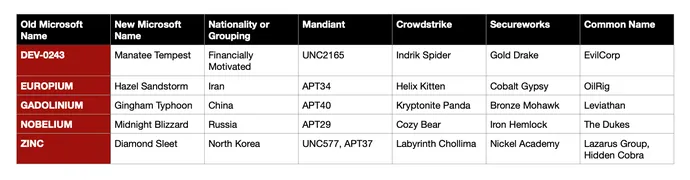

Last week, Microsoft changed its naming convention for threat groups, doing away with all-cap names derived from atomic elements, such as ACTINIUM, and adopting a two-name scheme based on storm terminology, such as Aqua Blizzard — the Russia-related group formerly known as ACTINIUM. The company adopted the new convention to indicate the interest of the sponsor of the attack group — Blizzard for Russia, Typhoon for China, and Tempest for financially motivated actors, for example — in much the same way that CrowdStrike and Secureworks create their names for threat groups.

Such monikers are a way to give clients and customers an easy way to remember the adversaries behind particular threats and attacks, says Sherrod DeGrippo, director of threat intelligence strategy at Microsoft.

“By giving them something that answers that and sticks in their reference memory, they can jump into deeper analysis and investigation faster,” she says. “We want to effectively protect and inform our customers; this is a step toward evolving that capability and making it more clear for security practitioners and other threat intelligence analysts.”

Unfortunately, having yet another naming convention also adds to the proliferation of labels for threat groups, a surfeit that — to some extent — muddies the already murky waters of threat attribution. There are at least eight names for the Iranian group that Microsoft called PHOSPHORUS, and 15 names for the Russian group known as Cozy Bear, including two former Microsoft names — YTTRIUM and NOBELIUM — and now its new Microsoft name, Midnight Blizzard, according to the ATT&CK database maintained by MITRE, a non-profit government research organization.

A lot of people are confused about what names apply to what groups, says Adam Pennington, ATT&CK lead at MITRE.

“There are a ton of different names out there, because there are a lot of companies that have gotten into this space … and so each of these organizations is coming up with potentially a little bit different definition of what this group is that they’re seeing. They each have a different intelligence picture.”

When a Cozy Bear Isn’t

In the 1990s and early 2000s, security firms often coined their own names for computer viruses, hoping that their name would stick as a demonstration that they were first to catch a particular threat. Yet others often attached a different name to a particular threat — thus, Conficker also answered to Downup and Kido, while the Blaster worm also went by MSBlast and Lovesan.

Yet while those names were pseudonyms for the same threats, attribution of threat groups is different, part art and part science, says Microsoft’s DeGrippo.

“Each vendor uses different data to assign actor attribution, with different levels of confidence,” she says. “Because each vendor approaches this analysis of a threat in a different way, they often don’t agree on attribution or only find partial overlaps, requiring each of them to create their own unique names to describe their unique view.”

Take the notorious Cozy Bear, a group of cyber operators acting on behalf of the Foreign Intelligence Service of the Russian Federation (SVR), who have operated since at least 2008. The group is perhaps most famously known for compromising the computers at the Democratic National Convention and as executing the supply chain attack that involved compromising SolarWinds. Cozy Bear is CrowdStrike’s name for the group, but both Mandiant and Microsoft had two names for the group — UNC2452 and APT29 for Mandiant, and NOBELIUM and YTTRIUM for Microsoft — highlighting that differences in analysis could lead to different conclusions.

In addition, with many nation-state actors, there is a lot of cross-pollination between cyber-operations groups, so it’s natural that vendors’ pictures of attackers would diverge, says MITRE’s Pennington.

“When you get into countries like North Korea and Iran, there’s often quite a bit of disagreement between different companies, where they draw the lines between groups and how many different things they pulled together into a single entity,” he says. “So, there are some solid differences depending on the intelligence that companies have and the parts of the threat group that they are looking at.”

The Adversary Problem Is a Bit of a Problem

Threat intelligence vendors and incident response firms like to say, “You don’t have a malware problem, you have an adversary problem.” With the firms tracking hundreds of threat groups, the multitude of names may make it harder for companies to determine who is attacking them.

Threat intelligence analysts are aware that poor attribution can undermine their efforts, so they take steps to make sure that attribution is correct and that the assignation of an attack to a new group of actors is done with care, CrowdStrike stated in a blog post on the topic.

“Only after a series of rigid analytic steps will an actor be given a name and added to CrowdStrike’s list of named adversaries,” the company stated.

Looking beyond the names, however, attribution does have significant benefits. Knowing that a group — whether it’s named APT28, Fancy Bear, or Forest Blizzard — targets political and governmental institutions can help companies and organizations determine whether they might be targeted. In addition, by noting the range of tactics that a group employs, a company can look for and guard against those efforts, once they have identified the group.

Will vendors ever be able to use the same name for the same threat group? Perhaps not, says Microsoft’s DeGrippo.

“This is something, honestly, that may never be solved completely,” she says. “The threat landscape moves very quickly, and we need to be able to link attribution to activities rapidly. Depending upon data sharing and consensus across a large industry with many vendors could slow down a security company’s ability to attribute, causing a gap in threat protection.”

Read More HERE