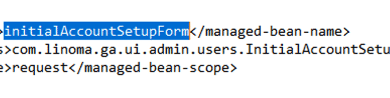

Unleash The Hash – ShadowHammer MAC Address List

Get the [almost] full list of MAC addresses that were targeted in the ASUS breach, and share our pain in the short story of extracting them.

TL;DR: The latest list of plain-text MAC addresses targeted in the ShadowHammer ASUS breach can be downloaded here.

Last Updated: 30/Mar/2019

You have probably heard of the ShadowHammer hack by now.

A truly disturbing case that shows yet again, that nothing can be 100% trusted, not even a formally signed update from a well known vendor.

According to available information, the threat actors have infected computers en-masse, but have targeted specific machines based on their MAC address.

The question of who did this and why is intriguing, but not one we were trying to answer in this case.

First thing’s first – if information regarding targets exists, it should be made publicly available to the security community so we can better protect ourselves.

Kaspersky have released an online tool that allows you to check your MAC address against a DB of victim MAC addresses (which is hidden).

Good on Kaspersky on one hand, but on the other hand, this is highly inefficient, and does not really serve the security community.

So, we thought it would be a good idea to extract the list and make it public so that every security practitioner would be able to bulk compare them to known machines in their domain.

If you are interested in the list it can be downloaded here.

If you are interested in learning how we extracted it, read on, it was a short yet sweet ride, kind of like the CTFs we love so much, and thank you Kaspersky for the challenge!

Phase I – getting the bulk list in binary format

In conjunction with the website, Kaspersky have released an executable that checks if your machine has been targeted. Naturally, since it is an offline tool, it means that the full list of MAC addresses has to be contained within that executable.

So, up goes IDA and we go hunting for the MAC list.

Before even taking a look at the disassembled code, we can hypothesize how such a tool might work:

- Extract local MAC addresses

- Calculate hashes for those addresses

- Compare the local list with addresses that are embedded in the executable

A quick look at the disassembly shows that the entire logic of the program was written inside WinMain() (classic security researcher coding style…).

Sure enough, the program follows the expected steps.

We can see that the first thing the tool does is extract the local MAC addresses and hash them.

Following that, we can immediately recognize two sets of nested loops, and further analysis reveals that there are actually two different lists the tool compares the hashes of the local MAC addresses to.

Finding the two lists is straightforward, and the total weight of the hashes is 19936 bytes.

Phase II – what the hash?!

So now that we have the list, and knowing that the threat actors used MD5 hashes, we have to brute force these MD5s, which should be pretty straightforward.

However, something doesn’t seem right from the get go.

MD5 hashes are 16 bytes (128 bit) long, but dividing the list of hashes by 16 yields 1246, which doesn’t make sense as we know from publications that there should be around 600 addresses.

Moreover, the hash comparison loops seems to work in 32 bytes increments, suggesting a different hashing algorithm than MD5.

We need to dig deeper…

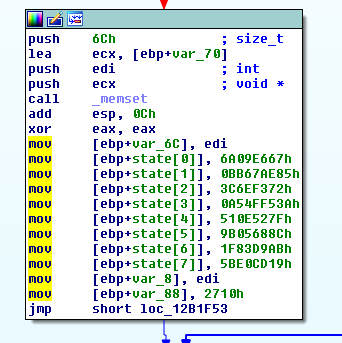

Looking at the hashing routine, we find this:

hashing routine constants

For people involved with cryptography, these constants are an instant tell-tale sign of SHA2-256. SHA256’s hash size is 32 bytes long, matching the comparison routine.

We don’t consider disassembling crypto code as a fun afternoon activity, and so we’ve opted to try the short path first. Let’s hash one of the few known target MAC addresses with SHA2-256 and see if we get a hit. Nothing in life is easy, especially not crypto, so of course, the approach failed, and we did not get a hit.

Little did we know that these are not vanilla SHA256 hashes at all.

Phase III – Who are you Mr. hash?

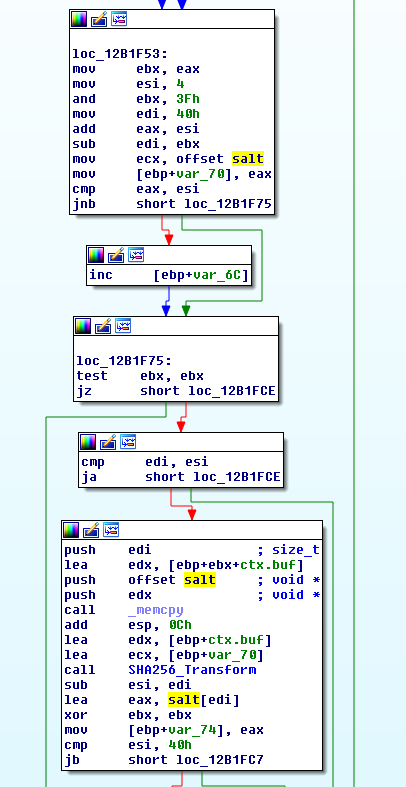

Reluctantly, we had to dig deeper into the hashing routine.

Following a reference implementation of SHA256 and the disassembly, we’ve noticed that the code calls SHA256_Transform (the inner function that performs transformations on the inner algorithm state) with a constant that seems to be four bytes long.

Disassembly of hashing routine

Well, “That must be it!”, they’ve salted the hash, we figured. But why would they do that? Are they trying to hide those MAC addresses?

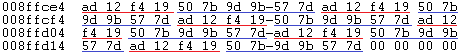

Anyway, we’ve tried the blackbox approach using known target MAC address hashed with the discovered salt (0xad, 0x12, 0xf4, 0x19) to see if we get a match, but it failed again.

Dynamically analyzing calls to the SHA256_Transform function demonstrated that the hash is actually calculated on repeated sequences of the salt + MAC address.

salt (0xad,0x12,0xf4,0x19) followed by 70:8B:CD:10:43:18

Revisiting the disassembled code, we can spot a constant (10,000) being used to break a loop. Could they be running the hashing algorithm 10,000 times with the salt?

Let’s have a go with the following code and test it:

$salt = "\xad\x12\xf4\x19"; $mac = "\x70\x8b\xcd\x10\x43\x18"; // 70:8B:CD:10:43:18 (one of the few MD5s that were published and we brute-forced) $ctx = hash_init("sha256");

for($i=0;$i<10000;$i++) hash_update($ctx, "$salt$mac"); print hash_final($ctx);

Which yields “cde5d9a781e56f37351be146a4389a975a9838f0fe13710f3501202e8ca2fb7a”. This hash is part of the list of hashes embedded in Kaspersky’s executable. Yes! This is definitive proof!

Now that we have the hashing algorithm we can start brute-forcing.

Phase IV – We’re going to need a bigger cat

You can write your own code to brute-force hashes, but there is a lot of know-how involved in making the most use out of your Hardware.

For us, Hashcat was an obvious choice, given that it’s an open-source and flexible tool.

We tried stretching Hashcat’s features to their fullest, but couldn’t find a way to use the algorithm we saw in Kaspersky’s code ( If you know of a method, please share in the comments).

After a sigh that was heard throughout the continent, we set about to modify Hashcat to support the new scheme. Trying to compile & build most open-source cross-platform projects on Windows is a pain and Hashcat is no different, so we’ve switched to our Linux box.

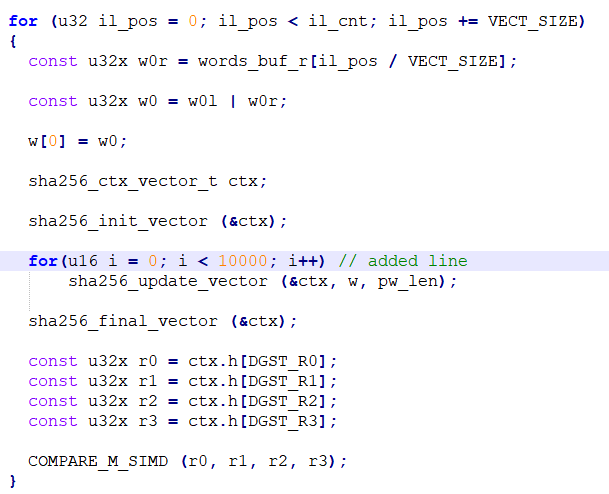

Actually, it was surprisingly easy to enhance Hashcat and all we had to do is add two lines of code inside the OpenCL implementation of SHA2-256 (Hashcat algorithm #01400), as follows:

Hashcat code modification

And with that we were good to go.

Phase V – She’s not gonna hold, Captain!

Trying to brute-force the entire space of MAC addresses, hashed using SHA256 on the repeated salt+MAC is not feasible in a reasonable amount of time and resources.

Therefore, we had to reduce the address space.

A MAC address is comprised of the prefix (3 bytes) and a suffix (3 bytes). Prefixes are allocated to vendors.

We used a couple of different strategies to limit the prefixes we were targeting:

- Limit to only known, assigned MAC address prefixes.

- Reduce further by following information released by other security vendors: 360 Threat Intelligence Center tweeted a nice infographic detailing the distribution of vendors of targeted MAC addresses. We could use that list to limit the prefixes we were brute-forcing.

- Limit to prefixes assigned to AsusTek.

Even with all of those strategies in place, brute forcing a single prefix was going to take us ~3 hours on our modest hardware. With a narrowed down list of around 1300 prefixes, that meant 162.5 days, a tad bit more than we would have liked.

Phase VI – victory

With that in mind, we realized that to do brute-forcing you need a brute!

Enter Amazon’s AWS p3.16xlarge instance.

These beasts carry eight (you read correctly) of NVIDIA’s V100 Tesla 16GB GPUs.

As Al Pacino once said – “Say hello to my little friend!” 🙂

The entire set of 1300 prefixes was brute-forced in less than an hour.

So far, we’ve managed to extract 583 out of 619 hashes, others probably have different vendors associated with them.

If you’ve found a MAC address that is not on our list, please contact us and we’ll update accordingly (or share in the comments section).

Thanks again Kaspersky for an enjoyable afternoon!

READ MORE HERE